Can laneway homes fix Toronto's housing market crisis?

With many Canadians being priced out of Toronto’s housing market and the municipal government trying to find ways to increase density, the city has relaxed its rules around laneway housing.

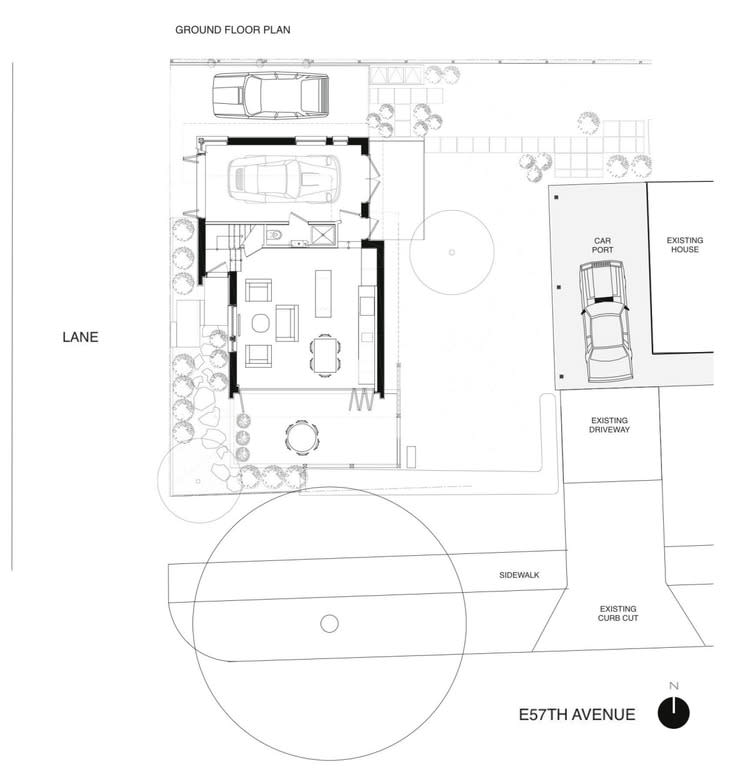

A laneway house is a secondary home built onto a laneway of someone’s residential property that is often, but not always, completely separate from the primary home. In Toronto, the city is asking city planners to investigate a plan for laneway housing that would see services such as heat, water and sewage delivered from the main house to the secondary residence. The home would not be completely self-sufficient.

This is an improvement from 2006 when laneway housing was only permitted if there were no privacy, overlook, shadowing and engineering servicing implications. The city’s example of a permitted circumstance was a house having frontage onto a public park, but serviced from a lane in the rear. Even still, those who happened to have a laneway house under those circumstances were charged more for city services such as snow removal and garbage collection.

But while Toronto is in the very early stages of its laneway housing experiment, Calgary and Vancouver have firmly established rules and regulations around laneway housing and has allowed them in those cities for a number of years.

“Vancouver is the leading city in North America and probably the world when it comes to secondary dwellings,” says Bryn Davidson, co-founder and president of Lanefab, a Vancouver-based custom home design and construction firm that has the distinction of building the first laneway house in Vancouver.

The Conditions for Laneway Housing

Davidson says there are four factors that have led to the proliferation of laneway houses in Vancouver and, similarly, Calgary and Toronto. One is that it’s very expensive to live in these cities – the average two bedroom in Vancouver is listed at $1,423,400, with a rental vacancy rate of 0.7 per cent. In Toronto, the average for a two bedroom is still quite high at $856,000 with a rental vacancy rate of 1.3 per cent.

In Calgary’s case, the motivation for laneway houses aka backyard suites or secondary suites is a little different. Many home owners want to be able to support an older family member into old age or a son or daughter just starting out. Some want an income property, but don’t want the renter living in their house in a basement suite and would rather have the separate entrances and exits a laneway house provides. For the people looking for a laneway house, it affords them the opportunity to still live in a desirable area with good schools and public transportation when there’s no more room in the neighbourhood for a conventional detached house.

“It’s a very easy way to increase density without tearing down single-detached homes and putting in townhouses or apartments because in Calgary the housing stock is pretty new and of quite good quality,” says Carol McClary, technical lead planner for the City of Calgary and a development authority who can approve laneway house applications. “We want to allow people some flexibility and increase density in our inner city community where they have good access to everything. Then, we’re not destroying the community to increase density. It’s very subtle,”

But laneway houses aren’t for the faint of heart, the initial investment in building one can be quite expensive and time consuming.

The cost and expense of laneway homes

“A city isn’t going to do laneway housing if there’s cheaper options to build housing because a laneway house is a fairly expensive option,” says Davidson.

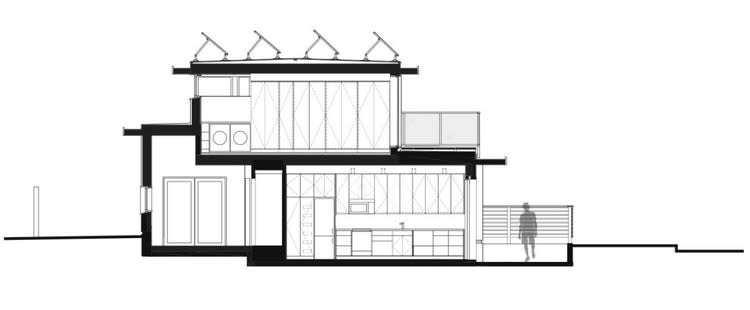

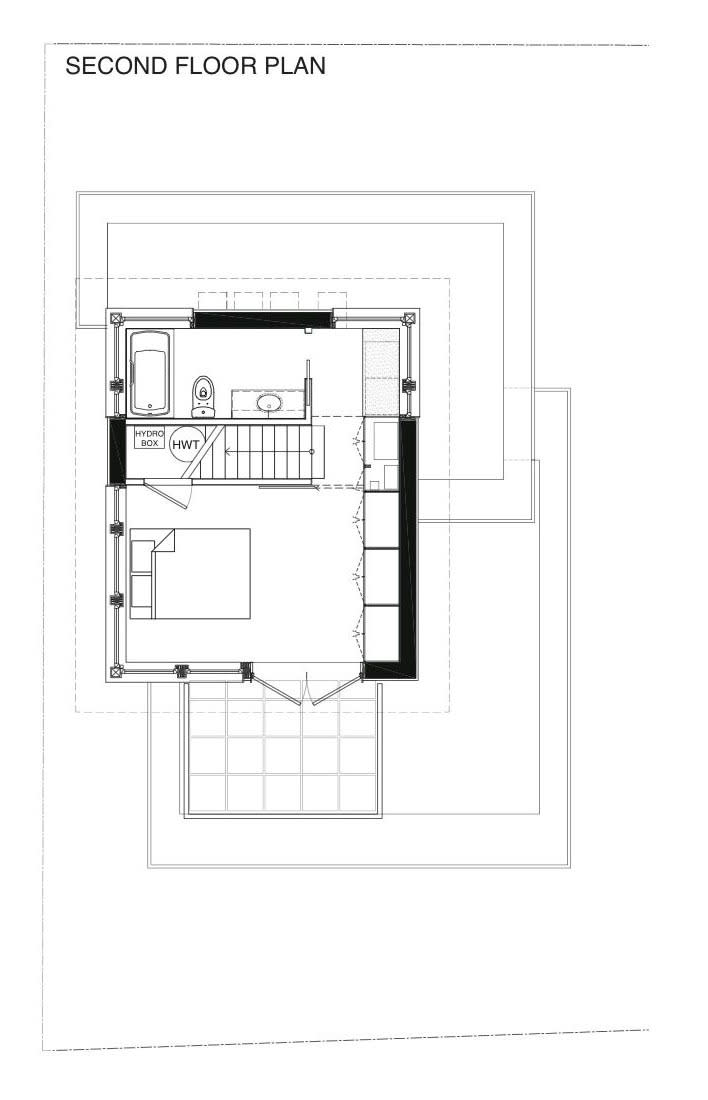

“A laneway house in Vancouver will generally cost $26,000 just in permit fees and then a similar amount goes to design and engineering. Plus, you have to pay for new sewer connections, new water connections and a whole bunch of landscaping which could run you around $80,000 in costs outside of design and construction. If you want our company to do your laneway house you’re looking at $350,000 to $400,000 all in for 700 to 1,000 square-feet.”

Plus, getting permit approval can take up to six months in a busy urban centre like Vancouver. Understanding the expense and hassle, Calgary tries to make it easier by not charging for the permits.

“We want to encourage people to build these homes so we’re going to help any way we can,” says McClary. “Even if where you live isn’t zoned for a laneway house, you can approach City Council and ask to be rezoned.”

There are also a lot of rules around privacy, overlook and blocking the light from your neighbour’s home.

Vancouver, Calgary and Toronto were ripe for laneway housing because there are a lot of basement suites, so the cities were already used to secondary dwellings. The three cities also have an extensive network of laneways that aren’t as common in other cities. Toronto, for example, has around 250 kilometres of unused laneway space right now.

Laneway lessons from the leader

But the reason Vancouver is so much further ahead in the proliferation of laneway housing than even Calgary or Toronto is because the municipal government changed the extremely common single-family zoning bylaw, which allowed laneway housing across the whole city. |It wasn’t just a pilot project confined to certain areas and such a commitment to this housing alternative translated to making laneway houses possible on roughly 65,000 properties throughout the city. Also, unlike Toronto’s proposed plan, laneway houses in Vancouver are allowed to be completely independent from the primary residence.

“In Vancouver everything has to be separate,” Davidson explains. “Separate sewer connection, separate address, separate everything. But it’s allowed to be additional density, so [you get] more floor-area and an additional dwelling unit. It doesn’t matter what you’ve done to your main house — you can almost always have a laneway house.” With very few conditions placed on the main house and with the city only requiring one parking space on the property, laneway houses took off in Vancouver.

“Our clients are very excited about the developments in laneway housing in Vancouver because it gives them another housing option that’s nicer and more affordable than anything else on the market,” he adds.

Of course, there was the typical initial pushback when the bylaw that allowed laneway housing in Vancouver was passed. People didn’t appreciate that new density was going into single-family neighbourhoods. But doing it citywide and ensuring that your neighbours couldn’t stop you meant that laneway houses were there to stay on the west coast.

“In a lot of cities, a lot of the work you do depends on neighbour approval and that’s a sure-fire way to kill the program and make sure nothing happens,” Davison says. “Being able to do this without neighbour approval was one of the key features of making it scaleable. That’s a lesson that has to go out to every city in North America because without it, single families can really exacerbate the housing crisis.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance