The Worms of Chernobyl Have Apparently Conquered Radiation

The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has been a hot bed of genetic study, as scientists examine how various species react to long-term radiation exposure.

While the the 1,000-square-mile zone has been host to cases of rapid evolution and other evolutionary changes, at least one animal—a common worm—appears completely unaffected by radiation exposure over the passing decades.

Scientists hope that, by understanding the strains of nematodes that are resilient to carcinogens, they can aid humans in their fight against cancer.

For the past decade, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (CEZ) has been a 1,000-square-mile laboratory of sorts, as scientists uncover the mutations and genetic abnormalities induced by a continued exposure to high levels of radiation. Tree frogs that should be green are instead black, feral dogs have displayed genetic differences when compared to nearby populations, some birds have seemingly adapted to the surrounding radiation, and wolves in the area have developed reported resistance to the radiation’s usual cancer-inducing effects.

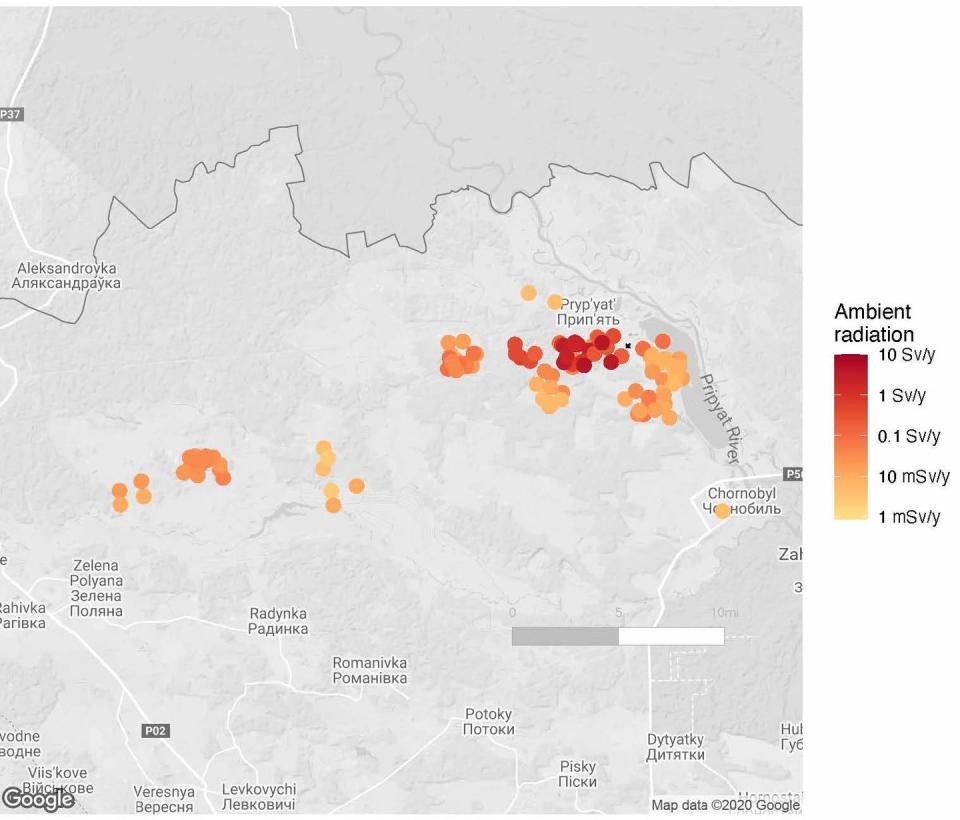

The same can’t be said for the common microscopic nematode Oscheius tipulae. Scientists from the U.S. and Ukraine visited the CEZ to study how prolonged exposure to radiation impacted the region’s worms. After collecting worms from various areas with differing amounts of radiation exposure, the scientists surprisingly concluded that the worms’ genomes exhibited no signs of damage from the area’s high-radiation environment. The results of the study were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Chernobyl was a tragedy of incomprehensible scale, but we still don't have a great grasp on the effects of the disaster on local populations,” first author Sophia Tintori, a postdoctoral associate with the Department of Biology at NYU, which led the study, said in a press statement. “Did the sudden environmental shift select for species, or even individuals within a species, that are naturally more resistant to ionizing radiation?”

Nematodes proved the perfect test subjects to examine this question, as they live everywhere and are incredibly short-lived. That means they churn through many more generations than most vertebrates. Tintori and her team collected samples in the field from soil and rotting fruit, and isolated established cultures from each worm. Because worms are so resilient, scientists could cryopreserve the worms for later study—effectively halting genetic evolution in its tracks.

From the nearly 300 worms originally gathered, the team narrowed their focused to just 15 worms from the species Oscheius tipulae—a common nematode found in non-desert soils around the world, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The researchers sequenced each worm’s genome and compared them, using several different analytical techniques, to five specimens of the same species found in other, non-radiated parts of the world.

The results? Nada.

“This doesn’t mean that Chernobyl is safe—it more likely means that nematodes are really resilient animals and can withstand extreme conditions,” Tintori said in a press statement. “We also don’t know how long each of the worms we collected was in the Zone, so we can't be sure exactly what level of exposure each worm and its ancestors received over the past four decades.”

The scientists also conducted an experiment to see how the 20 worm strains (15 from the CEZ and five from around the world) tolerated DNA damage. The worms exhibited different tolerance levels, but there was no correlation between radiation exposure of their ancestors and their heartiness. This means the Chernobyl worms “are not necessarily more tolerant of radiation and the radioactive landscape has not forced them to evolve,” according to the researchers. The team hopes that understanding which strains were more sensitive to DNA damage will help understand how carcinogens impact some humans more than others.

While various vertebrates experienced genetic mutation following that fateful explosion of reactor 4, for the worms of Chernobyl, life just kept on ticking.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance