William Watson: They got a Nobel Prize for that?

There probably haven’t been many official Nobel Prize appreciations, not even in the literature category, that make mention of It’s a Wonderful Life, the 1946 Frank Capra movie starring Jimmy Stewart and Donna Reed.

The movie was not a great success when first released. It was thought too dark: a man looks back on his life on Christmas Eve 1945 and concludes it was all for naught. But it has since become a classic. It’s especially beloved by economists. There’s a scene in which in the depths of the Great Depression, Stewart’s character, bank owner George Bailey, calms a run, i.e., a mob of his customers clamouring to withdraw their money because of planted rumours the bank’s going bust. His neck veins bulging with passion, Bailey/Stewart explains to them that of course the bank doesn’t have all their cash immediately to hand: that money is invested in their mortgages and businesses. That’s how banks work: borrowing short and lending long, which puts them, and any institutions like them, at mortal risk when depositors think their money may be in danger. It’s the reason we now have deposit insurance. The speech works. George manages to calm them all by patiently handing out all the cash he has, including two thousand of his own dollars that were supposed to pay for his honeymoon.

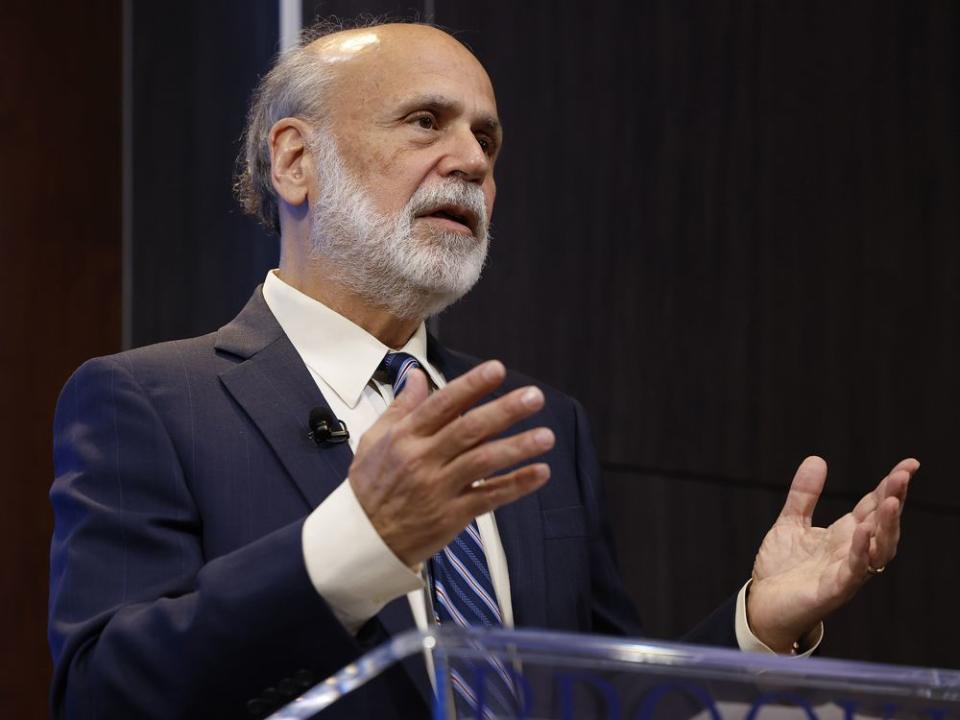

Unfortunately, such speeches didn’t often work during the Great Depression. The U.S. lost 10,000 banks during the 1930s, most of them small, community-based banks, which in many states were the only kind allowed by law. In their 1963 Monetary History of the United States, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz showed how the resulting contraction in the money supply reinforced the economic downturn that followed the stock market crash of 1929. In a 1983 paper, Ben Bernanke added the idea that, apart from their effect on the money supply, the bank collapses left a big hole in the system by which lenders exercised control over borrowers, and with that gone there were fewer ways to invest safely.

For that key insight and others, Bernanke, Douglas Diamond of the University of Chicago and Philip Dybvig of Washington University, who helped make our intuitive understanding of banks consistent with economists’ formal models, this week won the Nobel Prize in Economics. (Diamond was a year behind me in graduate school, which induced a fleeting George Bailey “what have I done with my life?” moment when the news came through).

My friends in engineering and the hard sciences will find this award perplexing. The key insight was available for all to see in a 1946 Hollywood movie (they will say) and you get a prize just for verbalizing it or formalizing it in mathematics?

Like many of us as we age, I spend more time reading obituaries (and trying to suppress Bailey moments). The ones I like best are of crusty old men and (less often) women who decades ago invented something whose use is indisputable. Recently there was one for Nick Holonyak, Jr., who died last month in Urbana, Ill. The son of a Ukrainian immigrant who had walked from his disembarkation in New York to Pennsylvania, where the coal was, Holonyak decided after one 30-hour shift on the Illinois Central Railway that manual labour was not for him, went to school and became an engineer — electrical, not locomotive. In 1962, while working for General Electric, he demonstrated the first light-emitting diode. “It’s a good thing I was an engineer and not a chemist,” he later said. “When I went to show them my LED, all the chemists at GE said, ‘You can’t do that. If you were a chemist, you’d know that wouldn’t work.’ I said, ‘Well, I just did it, and see, it works!’ ”

That’s more the model of scientific discovery people have in mind when they think of Nobel Prizes. It’s understood something may be possible but nobody has actually done it. Then someone does. What hadn’t existed now indisputably exists. And the person or persons responsible get the Nobel Prize (though responsibility may not be completely clear: it was two Japanese scientists who got the Nobel for LEDs for having, in 1993, made the diodes do more colours than red, which was all Nick Holonyak’s diode did).

By contrast, in economics there are few true “Eureka!” moments. This year’s Nobel citation argues that without Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig’s insights, we wouldn’t have the modern, “macro-prudential” banking regulation that, it argues, prevented an economic collapse in 2008 or another in 2020 — with the 2008 rescue mission being presided over by Ben Bernanke himself as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.

But we’ll never know, will we? Even if the three economists had gone into electrical engineering instead, policy-makers might well have figured out that letting the U.S. or even the world banking system go bust was not a good idea. If we could run history over again, we could try that experiment and know for sure. But we can’t.

Which when you get down to it is the basic problem with the economics version of science. From the single run of history that you observe you have to try to figure out which variables caused the results you see. In that respect, it’s actually harder than the hard sciences.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance