William Watson: All Friedmanites now? If only!

In 1914, the poet Carl Sandburg called Chicago “hog butcher for the world … stormy, husky, brawling … city of the big shoulders.” In economics, it’s thought of as the city of the big brains … sharp, skeptical minds … butchers of sloppy, half-baked, wishful thinking. That’s mainly due to the economics department of the University of Chicago and its school of free-market thinkers that rose to peak influence in the mid-20th century, winning seven Nobel prizes in economics (Friedman, Schultz, Stigler, Coase, Becker, Fogel, Lucas).

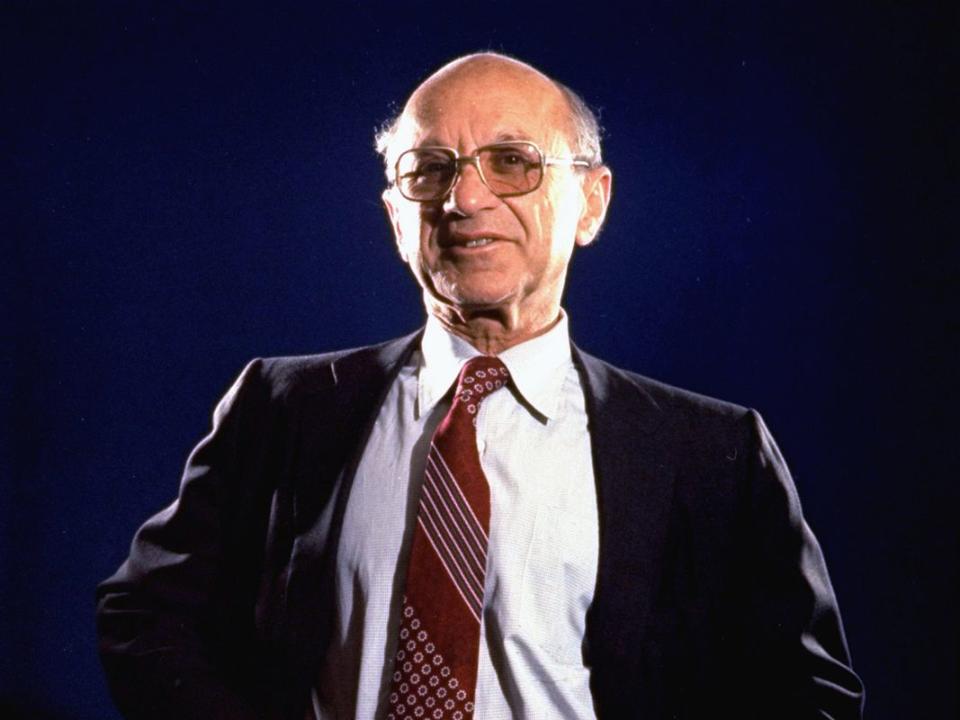

Elsewhere on this page, Philip Cross reviews the new book “Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative,” by Stanford historian Jennifer Burns. She uses the word “conservative” in the customarily confused American way, meaning: “liberal,” as in classical liberal — i.e., not quite libertarian but certainly devoted to individual freedom. In 1962, Friedman published a famous collection that he called, simply, “Capitalism and Freedom.” Today you could only juxtapose those words in a title if it were “Cursed Capitalism and So-called Freedom.”

Are we all Friedmanites now, as Cross concludes, quoting Democrat and neo-Keynesian Larry Summers paraphrasing Friedman himself? If only!

It depends what you mean by Friedmanite, of course. If you mean analyzing human behaviour by looking at what people’s incentives are and trying to figure out what they’ll do in given situations, especially situations a government is trying to control with policy, then yes, absolutely, that’s what economists, good ones, are always trying to do.

That’s not all due to Friedman, it’s what economics has been doing since its beginning. But Friedman was one of the most brilliant and public practitioners of working things through to see where different policies might lead and how people’s reactions might undermine what policymakers were trying to do. So he’s definitely a modern model for that kind of thinking.

How we think about inflation is also largely Friedmanite. Almost nobody believes in the permanent trade-off between inflation and unemployment. (“Almost” is required because these days many bad ideas, like many diseases we thought had been wiped out, are making a comeback.)

Surprise inflation increases employment because it lowers people’s real wages, making employing more of them a better deal for employers. But fool me once, etc., etc. Once people are on the lookout, inflation doesn’t fool them anymore. They insist on wage increases to match it, so their real wage doesn’t go down, and their attraction to employers doesn’t rise.

Other economists were figuring this out in the 1960s — most notably, Edmund Phelps, Nobelist in 2006 — but in 1967 Friedman had the bully pulpit as president of the American Economic Association and staked his claim first.

Are we all Friedmanite now in the sense of paying attention to the money supply? MV=Py is the famous monetarist “equation of exchange.” M is the stock of money (but which money? cash? cash plus demand deposits? cash plus all liquid deposits? if so, how liquid?). V is the velocity of money, the speed with which it moves through the economy, which depends on financial rules, institutions and technology. P is the price level and y is real income or GDP, so that Py is nominal income or GDP. Increase M and if V is constant, then Py must go up. If you’re already at capacity output, only P can rise, hence: inflation.

(Note that Friedman’s license plate used the “transactions” version of the equation, MV=PQ, with Q being the total quantity of transactions financed by money. Transactions exceed income/GDP. GDP is final output — e.g., bread. But lots of intermediate transactions go into getting to bread — e.g., growing wheat, making flour, baking, packaging, delivering it and so on. They’re all financed with money.)

Jennifer Burns argues Friedman was the greatest economist of the 20th century. Matthew Lau wrote here recently that he was simply the GOAT, the greatest of all time. Both views may suffer from recency bias. John Maynard Keynes dominated the first half of the 20th century easily as much as Friedman did the second. As for all time, well all of time is a long time!

Among economists who wrote in English, I go with either Adam Smith, for his voluminous insights into markets and market behaviour or, possibly the smartest economist ever, David Ricardo (1772-1823). Ricardo wrote definitively about at least three crucial concepts in economics.

Comparative advantage, which, as Paul Krugman explains in “Ricardo’s Difficult Idea,” is more complicated than it sounds, or than even Adam Smith thought it was.

Rent, which is not what you pay your landlord but rather is a payment you don’t actually need to get you to do what you’re doing — and which everyone would like to have, as Jim Balsillie wrote in this paper over the weekend.

Terence Corcoran: Better start hoarding Pepsi and Frito-Lays

Opinion: Canadians are paying for their governments' debt addiction

William Watson: Harvard and the high economic cost of potholes

And debt, which may or may not affect people’s current behaviour, which means government debt may not stimulate the economy but may instead suffer from “Ricardian equivalence,” in which people discount its current impact because they understand its future implications.

Interesting question: would it be better for the country if our Bank of Canada governors read more Friedman or our finance ministers more Ricardo? Columnists being free not to choose, I say let’s have both.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance