UNESCO wants to protect sites deep in the ocean that don’t belong to any country

The United Nations agency tasked with protecting the world’s cultural and environmental wonders is setting its sights really low. As in, the bottom of ocean.

UNESCO has called out five areas in the high seas—from habitats of delicate coral to one of white sharks’ favorite hangouts—that it thinks should be among the next generation of World Heritage Sites.

UNESCO is trying to protect deep-water octocorals, a soft coral. (Courtesy NOAA)

The designation of “World Heritage Site” is more than a bragging right or marketing slogan. Countries apply for the designation to access the World Heritage Fund, which provides money to help preserve these areas.

There are currently 1,052 places worldwide have been declared UNESCO World Heritage sites. The list spans from Persepolis to Grand Canyon National Park, from Lake Turkana to the Galapagos Islands.

There are already some underwater sites included on the list, such as Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, but ecosystems out on the high seas—in areas that are not governed by any sovereign nation—are a gray area for UNESCO. That’s because governments are the ones who have to ask UNESCO to consider adding the site to its prestigious list, and ecosystems in the high seas don’t have anyone to apply for them.

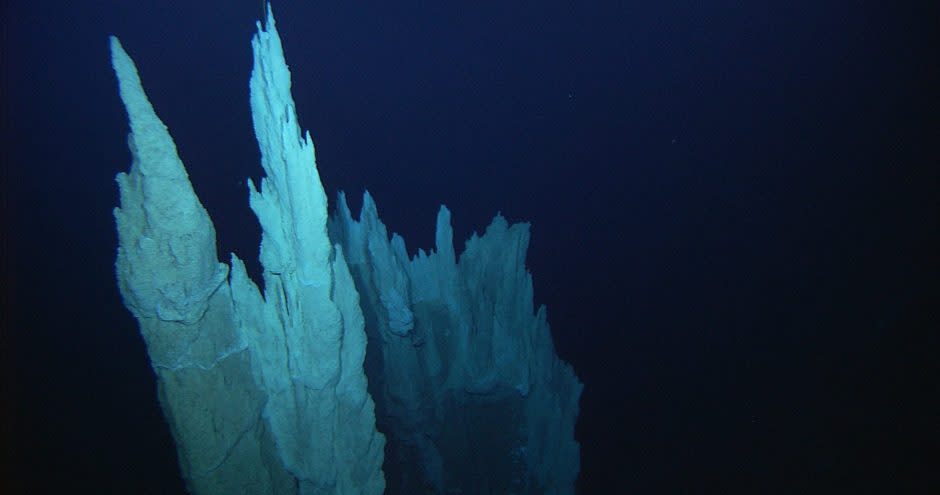

The carbonate spires of the Lost City Hydrothermal Field are on UNESCO’s protection wish list.

“Although these sites are far from our shores, they are not safe from threats, whether it be climate change, deep seabed mining, navigation or plastic pollution,” says UNESCO. It argued for the inclusion of five areas in the high seas in a report (pdf) last week (Aug. 3):

The Costa Rica Thermal Dome, a nutrient-rich area of the eastern Pacific where species like blue whales and leatherback sea turtles migrate and feed.

The White Shark Café, a stretch of the Pacific between North America and Hawaii that’s a habitat of white sharks

The Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean that’s home to free-floating algae.

The Lost City Hydrothermal Field, a deep-sea system of active hot springs and carbonate spires.

The Atlantis Bank, a sunken fossil island in the sub-tropical Indian Ocean that’s home to deep-sea coral species and large anemones

It’s not yet clear how the designation will affect those sites. Often, the UNESCO seal gives sites much more international attention and can lead to a flood of tourists to the areas it is trying to protect—especially if there’s the chance that it is endangered.

In the past, many UNESCO sites were far too remote for many travelers to access. But tourist infrastructure has adapted to demand, and even in the cases of these far-flung, deep sea sites, some intrepid (and wealthy) travelers will probably want take the dive. It could be a while, though, until they make it that deep. The highest point of the Atlantis Bank is 700 meters below sea level, and the record for deepest human Scuba dive is about twice as close to the the surface as that. To venture into many of these areas, you’d need a submersible vehicle (and possibly some government funding).

An undersea cave rental on Airbnb probably isn’t around the corner, but deep-sea tourism isn’t an impossibility. We’re edging toward lunar tourism, after all.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz:

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance