Tax breaks & loopholes cost KY taxpayers more than $9 billion, report says

Every two years, as Kentuckians are working to balance their own personal budgets, the General Assembly allocates funds for its state budget. In 2022, the state’s General Fund budget was set at $13 billion annually.

But looming over that decision is an opportunity cost that Kentuckians don’t have: $9.1 billion in state funds “spent” on tax breaks and loopholes.

The state of Kentucky defines these as “tax expenditures” — exemptions against the base of a tax. It’s an all-encompassing term that refers to tax loopholes, breaks or any other exemption that allows something to be taxed less than it would otherwise.

Kentucky is set to give out about $9.1 billion this fiscal year, which began July 1 and ends June 30, 2024. Current projections for the two fiscal years after that are around $9.2 billion and $9.6 billion.

Those numbers represents the “opportunity cost,” or the amount of revenue that could have been collected if all exempted commodities or services were taxed at the base tax rate.

For example, this fiscal year the exemption of medicine is projected to cost the state $924 million in tax revenue that it could have received if medicine were taxed at the normal 6% sales tax rate.

According to the latest tax expenditure report produced by the Office of the State Budget Director in October, tax expenditures will amount to almost $9.1 billion for the current fiscal year. Revenues into the state General Fund are projected to total $15.4 billion.

Some of the biggest tax expenditures are largely agreed upon. The sales tax exemptions for medicine, food and residential utilities account for close to $2 billion in the state’s tax expenditure total for this fiscal year.

“I categorize tax expenditures in three ways, and the first category is ‘absolutely defensible, shouldn’t be touched.’ Utility bills, groceries, pharmaceuticals, and healthcare are in that category,” said Andrew McNeill, a former member of GOP Gov. Matt Bevin’s cabinet who’s now president of the Kentucky Forum for Rights, Economics & Education.

It’s considered to be a conservative-leaning think tank.

McNeill’s other tax expenditure categories are “possibly defensible” and ones that should “absolutely” go away. An example in the latter category is that railroad companies are exempted from the state’s 19.6 cents per gallon gas tax.

And it’s not just conservatives like McNeill who think tax expenditures should be more closely examined.

Jason Bailey, executive director at the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, viewed by many as a progressive-leaning think tank, is leery of many of the state’s tax breaks and loopholes.

His organization has long been critical of Tax Increment Financing projects, known as “TIFs.” Those are methods to finance real estate development costs where developers get a portion of their tax dollars reimbursed for improvements. They’ve been derided as “corporate welfare” from conservative budget hawks like McNeil and progressives alike.

However, though some on both ends of the political aisle are interested in tackling the issue of tax expenditures, the question of “to what end” is where they diverge.

Bailey and McNeill use the revenue lost due to tax expenditures as a way to advance very different responses to the key question facing lawmakers as they stare down this upcoming year’s budget session: to invest in expanded programs or to save with an eye toward further cutting the state’s income tax.

Bailey opposes several tax expenditures in part because they represent cash that could be used to fund important government programs like education.

McNeill opposes them because the extra revenue provided would allow Republican legislators to pursue tax cuts at an even faster clip than they already do.

Rep. Ken Fleming, R-Louisville, who was a key co-sponsor of the bill that put Kentucky on a path to do away with income tax, said that addressing tax expenditures can be part of Republicans’ overall tax reform strategy.

Fleming led a task force on the matter in 2018, which culminated in a detailed report with specific recommendations. The group’s biggest to-dos – to sunset all but 10 of the biggest tax expenditures and to create a Tax Expenditures Oversight Board – were not followed up on.

However, Fleming said there’s a chance the General Assembly might look more closely at tax expenditures in the future.

“I hope we get some legs underneath this bill because if there’s some realization that it could help satisfy those triggers, then obviously that’d be helpful,” Fleming said.

Regardless of where a tax expenditure falls on the political spectrum, it’s probably got some staying power, according to Kentucky Center for Economic Policy Executive Director Jason Bailey.

Tax expenditures have proven difficult to change via legislative action, in large part because they’re not scrutinized in the same way that budget line-items have to be when the legislature drafts the state’s spending document every two years.

“They’re continuing to enact (tax expenditures) in the legislature. The part of spending that’s growing is through the tax code, as opposed to spending on the budget,” Bailey said. “Spending through the budget is a lot more transparent and you have to fight for it every two years. When you put in place a text expenditure, generally it’s there forever.”

After a Herald-Leader investigation on the matter of tax expenditures as well as Fleming’s task force, both in 2018, a handful of new tax expenditures have been approved to benefit heavy equipment rental companies and prefabricated home retailers among others.

Sales and Use Tax

At close to $3.7 billion, exemptions on Kentucky’s sales and use tax take up the largest share of Kentucky’s tax breaks.

Food, medicine, and residential utilities take up more than half of that total at nearly $2 billion.

These expenditures are generally agreed upon.

Beyond that, the largest category of expenditure is purchases made by the state, cities, counties and special districts. If those were subject to the state’s 6% sales tax, they’d have generated $470 million this fiscal year. That designation includes school boards, which in many Kentucky counties are the largest employers.

Sales tax expenditures from transactions by non-profit, charitable and religious organizations are projected to cost about $388 million this fiscal year.

An exemption for “industrial supply” on repair, replacement, or spare parts as well as machinery for new and expanded manufacturing in the state costs $283.5 million.

A big chunk of the sales and use tax exemptions are targeted towards farmers. That includes $252 million on exemptions for livestock – which includes poultry, ratite birds, llamas, alpaca, aquatic organisms, buffalo, Cervids, embryos and semen, among others – farm chemicals and more agricultural purchases.

Exemptions on energy and energy-producing fuels, with a specific break written in for coal, costs a little more than $89 million.

Smaller sales tax breaks have drawn scrutiny as well. The Herald-Leader has covered exemptions on houseboats (fishing boat owners are taxed 30 times more than houseboat owners), gravestones and horse sales. Each of those tax breaks remain on the state’s books.

Individual income tax

Employer contributions for medical insurance and care is the biggest income tax exemption, amounting to an expenditure of more than $684 million.

Pension, retirement income and Individual Retirement Accounts are exempted to the tune of about $566 million per year. Up to $31,000 of a person’s retirement and pension income is exempted from the state income tax.

Bailey said he takes some issue with certain retirement income being exempted for people who make a lot of money in their retirement.

“We exempt a lot of retirement income, no matter how high your retirement income is. That’s a pretty big deal when you’ve got all these baby boomers retiring,” Bailey said.

“A lot of people in that age category, they roll off of the work into retirement and they quit paying income taxes on their first $31,000 of income even if they’re making a whole lot of money. That doesn’t make a lot of sense, and that one is hugely expensive.”

About $211 million in income tax is projected to be deducted this fiscal year from non-itemized tax returns.

Low-income Kentuckians receive a Family Size Tax Credity that is adjusted based on family size and income levels. That amount is projected to hit $152 million this fiscal year.

When asked what tax expenditures are worthwhile, Bailey pointed to programs like the Family Size Tax Credit. He said he’d push for the consideration of an earned income tax credit to further help poor Kentuckians or a child tax credit.

A federal child tax credit, which was briefly implemented during the pandemic and ended in 2022, played a role in cutting U.S. child poverty nearly in half.

Other high-dollar exemptions for income tax include the first $250,000 on the capital gains for individuals selling their primary residence ($141 million), capital gains on property transferred at death ($141 million), home mortgage interest ($123 million) and charitable contributions ($120 million).

Property tax

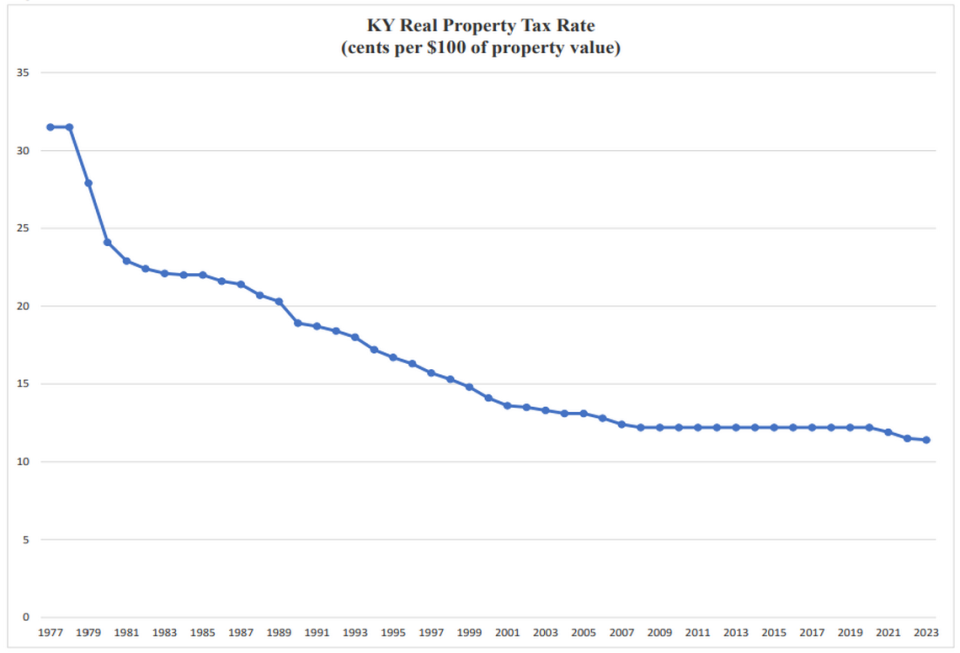

Thanks to a bill passed in 1979, when historic inflation was causing property values (and therefore property tax bills) to rise, the state of Kentucky’s real property tax rate has gradually decreased from 31.5 cents per $100 of assessed value then 11.4 cents per $100 of assessed value today.

The bill mandates that the tax rate drops to a compensating rate when property values rise by more than 4% in one year.

In this fiscal year, the total tax expenditure for the state’s real property tax due to that bill is almost $703 million.

The reduction of tangible property taxes on manufacturing machinery, pollution control equipment and radio/television equipment from 45 cents per $100 to 15 cents per $100, a special rate enacted in 1997, is projected to cost the state about $122 million.

Certain business inventories are taxed at a lower rate as well – 5 cents per $100 compared to the base rate of 45 cents per $100. Those inventories include certain machinery, motor vehicles held by a licensed motor vehicle dealer, raw materials, in-process materials (including bourbon and other distilled spirits) and certain heavy equipment.

In all, those exemptions will cost the state about $111 million this fiscal year.

A full phase out of the property tax on bourbon inventory – to the chagrin of many bourbon-producing localities – was passed last legislative session.

Other categories

Multi-tax incentive programs will account for around $470 million in tax expenditures this fiscal year. The two biggest tranches are an exemption on a limited liability entity tax that’s been in place since 2006 ($247 million) and the Kentucky Historic Preservation Tax Credit ($51.5 million).

Not included in the list of mult-tax incentive programs are Tax Increment Financing and Kentucky Tourism Development Act projects. Those are projected to cost about $47 million this fiscal year.

Lexington’s city government has recently shied away from Tax Increment Financing projects, which have been used for large developments like downtown’s Rupp Arena renovation, The Summit at Fritz Farm and more.

“(Tax Increment Financing projects) are, in my mind, the most clear definition of corporate welfare. The idea that the private developers who developed The Summit out in Fayette County should be getting subsidies on a retail-lifestyle place built on a greenfield outside Fayette Mall in one of the most prosperous parts of the county – that’s indefensible. But they do it because they can,” McNeill said.

A projected $145 million of $193 million in tax expenditures from the motor vehicle usage tax come from an allowance that reduces the purchase amount of a motor vehicle when a buyer trades in another vehicle.

Exemptions on the state fuels tax account for more than $62 million in tax expenditures. The biggest beneficiaries are railroad companies, who as of 1988 have been exempt from the fuels tax.

The railroad companies, McNeill said, have argued that they should be exempt because they don’t use the state’s roads – the fuels tax goes toward the state Road Fund.

“They were in favor of raising the gas tax on Kentucky drivers to support investments in infrastructure,” he said.

“They benefit from a robust infrastructure, and that’s the type of tax expenditure that they will die on the hill for, but I think is not terribly defensible and could go towards investments in roads, bridges and the infrastructure they depend on.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance