Special Report: Private equity star's picks shine, until cash-out time

By Lawrence Delevingne and John Tilak NEW YORK/TORONTO (Reuters) - Canadian financier Newton Glassman has long told his private equity firm’s clients that his big bet on casinos would yield a financial jackpot. Others haven’t been so sure. At the end of 2011, a year after Glassman’s Catalyst Capital Group Inc took control of Gateway Casinos & Entertainment Ltd, Catalyst told investors in a report seen by Reuters that it already had more than doubled their money and that its majority stake was worth US$475 million — for an implied equity value of the gaming company as a whole of US$699 million. But Catalyst was forced to abandon a planned initial public offering of Gateway in 2012 after investors balked at the firm’s valuation, according to two people familiar with the effort. In the ensuing years, Catalyst’s implied valuation of Gateway continued to climb, to more than US$1 billion as of Sept. 30, 2017, according to investor communications, all while Glassman repeatedly told clients to expect a sale that never happened. Now, under increasing pressure to liquidate a past-due private equity fund, Glassman is again attempting a Gateway IPO at a valuation of as high as US$1.95 billion, according to a Feb. 28 Bloomberg report. Under Catalyst’s direction, British Columbia-based Gateway has expanded its operations and just restructured its debt. Even so, Catalyst’s assessment of the impact of those moves on the company are more optimistic than those of ratings agencies Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, both of which still rate Gateway debt as “junk.” Michael Lewitt, chief investment officer at hedge fund firm Third Friday Management in Boca Raton, Florida, reviewed Catalyst’s valuation of Gateway and called it “extremely aggressive.” High valuations and delayed sales apply to more than just Gateway, Reuters has found, with potentially worrying implications for Catalyst’s four currently active funds and their big-money investors. Catalyst follows a “loan-to-own” strategy, acquiring the discounted debt of troubled companies, mostly in Canada and the United States, taking over the business in the case of a default or by other means, and then selling at a profit after improving operations. Early success using that strategy with Catalyst’s first fund established Glassman’s reputation as a savvy investor. It also has helped Catalyst attract enough investors to make it Canada’s third-largest private equity firm, with about C$6 billion (US$4.6 billion) in assets under management, according to data tracker Preqin. Since Catalyst launched its second fund in 2006, however, the firm’s record of double-digit annual returns has been based largely on its own assessments of improvements to its stable of distressed companies. When put to the test, at least four of Catalyst’s major assets have been unable to find buyers at the firm’s valuations, based on a Reuters review of Catalyst’s portfolio, multiple communications from Catalyst to its clients and regulatory filings, as well as interviews with people familiar with Catalyst’s operations, academics and financial analysts. Those major assets, plus expected payouts from pending litigation, made up US$3.3 billion – or more than two-thirds – of the overall US$4.7 billion of unrealized value across all Catalyst funds at the end of 2016, according to an April 5, 2017, report for clients. The assets include Gateway and Callidus Capital Corp , Catalyst’s publicly listed subsidiary that specializes in high-interest loans to distressed companies and that is itself a major holding of Catalyst funds. Failure to cash out can put additional pressure on Catalyst as funds approach the end of their lifespan, typically eight or 10 years, by which time all money – principal and profits – is expected to be returned to investors. Catalyst Fund Limited Partnership II, for example, was supposed to mature in April 2014 after starting to invest in 2006. But Catalyst has extended the deadline at least three times. The contrast between the picture Catalyst paints of its fund assets in communications with clients and how those assets perform when a sale is attempted shows that investors may not be able to count on the returns they expect. For now, though, any harm to Catalyst’s big investors is potential, rather than actual. Glassman could still repeat his early success with his current funds by managing to sell a handful of major assets at big gains. Glassman did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Catalyst and Callidus did not respond directly to requests for comment. In a letter to Reuters, David Moore, a lawyer for the two companies, disputed that Catalyst overvalues assets or has had trouble selling them. Reuters’ reporting, he said, is “based upon false and unreliable allegations.” In keeping with the industry norm, Moore said, Catalyst’s proposed valuations were reviewed by outside accountants PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. They were then separately reviewed by KPMG LLP, Catalyst’s independent auditor, which had issued unqualified audit opinions on Catalyst every year, Moore noted. KPMG and PricewaterhouseCoopers declined to comment. Moore stressed that Catalyst management’s pay is derived from proceeds from asset sales and that “valuations do not in any way affect Catalyst’s compensation.” He also pointed out that Catalyst had sold 23 assets in its history, 13 of them “in accord with applicable valuations.” He did not provide specifics on those sales. However, of the 17 completed sales showcased on Catalyst’s website, most were “substantially realized” in 2010 or earlier, often for US$50 million or less, according to a Reuters review of information Catalyst sent to clients. Nine of the sales were for the firm’s small first fund, which was largely wound down several years ago. Catalyst investors – generally locked in for the duration of a fund’s lifespan – include endowments for the University of Michigan, McGill University and the University of Toronto, public-employee pension funds in Montana and New Jersey, and major philanthropies such as the Rockefeller Foundation. They did not respond to requests for comment or declined to comment on the record, citing confidentiality agreements. Some said on condition of anonymity that they feared getting on the wrong side of Glassman, who has launched dozens of lawsuits in his career, most with Catalyst or Callidus as plaintiff. While in college, he successfully sued his father to force child support payments, according to Ontario court records. Gateway and some other major Catalyst fund holdings examined for this article are among the assets alleged to have been overvalued in two whistleblower complaints submitted in the past 18 months to the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), according to documents seen by Reuters and people familiar with the submissions. CARS AND PHARMACEUTICALS Private equity holdings can be difficult to value because they often lack ready markets to test their worth. Even when reviewed by third parties, a fund manager’s valuations are nonetheless open to interpretation. Private equity experts said that, in general, a pattern of delayed sales can indicate valuations that are too high. Lewitt, the hedge fund manager, said of Gateway and other assets examined in this article: “I wouldn’t invest a penny with any manager that employs these types of valuations.” Advantage Rent A Car is a case in point. Catalyst started investing in the Orlando, Florida, company with a US$22.2 million bet in 2013, and its total investment stood at US$310.5 million as of Sept. 30, 2017, according to client reports. As Catalyst’s exposure to Advantage through Funds III and IV has risen, so has its valuation of the company – even as larger rental car businesses have come under pressure from increased competition and the rise of ride-sharing outfits like Uber. Catalyst has long promised dramatic improvements at Advantage that would lead to a successful sale. In a 2014 letter to investors, it projected that within two or three years, earnings would top US$100 million. But for 2015, Advantage had a loss of US$31 million, according to an April 2017 presentation to Catalyst clients. A more recent investor letter put projected 2018 earnings at about US$20 million. Advantage has less than 1 percent of the U.S. market and was expected to generate revenue of US$327.7 million in 2017, according to market research firm IBISWorld. That puts Catalyst’s valuation of US$542.9 million as of Sept. 30, contained in a recent letter to investors, at a whopping 1.7 times revenue. Hertz Global Holdings Inc and Avis Budget Group Inc, the two biggest publicly traded car-rental operators in the United States, trade at less than half their 2017 revenue of US$8.8 billion each. Advantage did not respond to requests for comment. Another major Catalyst asset is Therapure Biopharma Inc. Glassman’s firm started investing in the Mississauga, Ontario, biotechnology company in 2006, and the commitment totaled US$82 million by the end of 2011. That year, Catalyst valued Therapure at US$202 million. In early 2016, it tried to take Therapure public at a valuation of C$867 million, according to a Reuters analysis of the offering documents. The same documents show that Therapure had operating losses in 2012, 2013 and 2014. The effort failed in part because Catalyst’s valuation was too high for most investors and in part because of difficult market conditions, according to two people with direct knowledge of the IPO process. In September 2017, Catalyst announced it had agreed to sell Therapure’s contract manufacturing business for US$290 million, which would result in a proportional payout for Fund II investors. That sale price – the deal has yet to close – is less than half the US$662 million at which Catalyst valued Therapure at year-end 2016, according to a Catalyst document provided to clients in April 2017. Therapure’s remaining business – plasma-based drug development and protein therapeutics products – probably isn’t worth more than US$100 million, according to two sources with direct knowledge of the company. The unsold business is not generating profits, one of the sources said. Therapure did not respond to requests for comment. Since Gateway Casinos’ IPO flopped in 2012, Catalyst has continually raised the valuation of its controlling stake — to levels that yield an imputed value for the gaming company as a whole of as much as US$1.95 billion, according to the Feb. 28 Bloomberg article. That article, attributed to anonymous sources, appeared as Reuters was seeking comment from Catalyst on the firm’s valuations of Gateway and other assets. Reuters could not independently verify that an IPO was imminent or determine the calculus underlying the US$1.95 billion valuation. Gateway operates about two dozen casinos, concentrated in western Canada and, more recently, Ontario, the country’s most populous province. It plans to invest more than C$300 million by 2020 to improve existing properties and build new ones, according to a February 2018 Gateway investor presentation. In mid-March, Gateway completed a sale-leaseback of some properties, yielding net proceeds to Catalyst of C$483 million. Catalyst said the transaction and a parallel debt refinancing would reduce Gateway’s debt from C$953 million to C$702 million – or 4.5 times earnings, according to a recent investor presentation. That’s in line with the typical debt-to-earnings ratio of between 4 and 5 for middle-market companies, based on Thomson Reuters LPC institutional loan data. However, it’s more optimistic than Moody’s assessment. The ratings agency estimated in early March that under the new financial plan, Gateway’s debt-to-earnings ratio wouldn’t drop below 5 for 12 to 18 months. And Standard & Poor’s said the number would climb to as high as 7.5 through 2018. Both ratings agencies still judge Gateway bonds to be non-investment grade “junk.” By comparison, rival Great Canadian Gaming Corp had a debt-to-earnings ratio of 2 as of Dec. 31, according to a financial filing. Moody’s also projects lower profits than Catalyst for Gateway. It did not elaborate on the full assumptions behind its numbers. A spokeswoman said the ratings agency’s calculations “reflect our conservative view of the earnings potential of the company’s assets.” Standard & Poor’s and Gateway did not respond to requests for comment. Moore, the Catalyst lawyer, said in a letter to Reuters that the firm’s work to improve Gateway had been “highly successful.” EARLY SUCCESS Now in his mid-50s, Glassman established Catalyst in 2002, after sharpening his skills at Cerberus Capital Management LP, the New York-based distressed-investment powerhouse. Catalyst’s first fund started investing in 2003. Within several years, it had scored big wins through private sales of its positions in companies like Cable Satisfaction International Inc; AT&T Canada Inc, later known as Allstream; and Royal Group Technologies Ltd. The US$185 million fund, tiny by private equity standards, ended up producing an average annual return of 32 percent over its lifespan, according to client reports. That’s far better than a benchmark return of about 17 percent for funds of the same 2003 vintage tracked by investment consultants Cambridge Associates. Catalyst’s early triumph helped drive billions of dollars to the firm over four additional funds raised between 2006 and 2015. Glassman has yet to successfully wind up any of those newer funds and return all money to investors, though the most recent one, Fund V, has returned hundreds of millions of dollars since 2015. It is not unusual for private equity firms to hold investments until near the end of a fund’s lifespan. However, data from Cambridge and Preqin show that three of Catalyst’s four active funds lag behind similarly aged funds in paying proceeds from asset sales to investors. With Fund II already past due, Funds III and IV are to mature in December 2019 and June 2022, respectively. Most of the value of these funds – about US$1.42 billion for Fund III and US$1.36 billion for Fund IV – is unrealized, according to an April 2017 client report. That’s more than 60 percent of the total value of each. Some of that unrealized value would come from payouts from litigation whose outcome remains uncertain. Catalyst filed two lawsuits against longtime rival and frequent adversary West Face Capital Inc and others after it lost a bidding process to buy Canadian wireless carrier Wind Mobile from VimpelCom Ltd in 2014. Catalyst claimed that it had an exclusive agreement with VimpelCom to buy Wind Mobile and that West Face and others engaged in improper conduct to win the deal and ultimately sell at a big profit. Judge Frank Newbould, originally hearing both cases in Ontario Superior Court, dismissed one of them, concluding that West Face and others, contrary to Catalyst’s allegations, had not used confidential information from a former Catalyst employee to make its winning bid. In his August 2016 ruling, Newbould wrote that he had “difficulty accepting as reliable much of the evidence” submitted by Glassman. He described the financier as “aggressive,” “argumentative” and more of a “salesman than an objective witness.” Catalyst appealed Newbould’s dismissal. That appeal was dismissed Feb. 21. The second Wind-related lawsuit, seeking C$1.3 billion in damages, was on hold, pending the outcome of Catalyst’s appeal of Newbould’s dismissal of the other case. In a report to clients, Catalyst told investors that its remaining Wind-related claim was worth US$446.9 million at the end of 2016 and that the firm has “a reasonable likelihood of success at trial.” Newbould, who has retired from the bench and now works as an arbitrator, was targeted by an undercover agent last autumn in a sting orchestrated by Israeli investigative firm Black Cube on behalf of Catalyst, according to West Face court submissions in separate litigation. The sting, West Face alleges, was designed to discredit Newbould and his dismissal of one of the Wind-related lawsuits. Newbould declined to comment. Black Cube gained attention last year for its work on behalf of Harvey Weinstein to undermine women and journalists in their efforts to go public with allegations of sexual harassment and assault against the Hollywood mogul. A spokesman for Black Cube declined to comment on questions related to Catalyst and Callidus. He said Black Cube always operates ethically and legally. In an April 2017 presentation to investors, Catalyst told clients of Fund III that without the expected litigation payouts, net annual returns as of end-2016 would fall to 8.9 percent from 11.7 percent. Ludovic Phalippou, a private equity expert at the University of Oxford in England, said Catalyst’s expected return on the Wind litigation was “extraordinarily” high, given that one of the cases was dismissed and that money that would have been used to buy the Wind assets were presumably deployed elsewhere. RELATED PARTIES One company Catalyst succeeded in selling on the stock market is Callidus, a distressed-lending business Glassman invested in, took over, and made a core holding. Glassman’s team took Callidus public in April 2014, raising C$252 million while still keeping big positions in the company for its four current funds. Catalyst funds provide guarantees for some of Callidus’s risky loans to distressed businesses. But those guarantees mean that investors in Catalyst funds can end up saddled with Callidus investments gone bad, such as Xchange Technology Group, an information-technology company that went bankrupt. The relationship between Catalyst and Callidus doesn’t end there. In May 2017, Callidus said in its first-quarter earnings report that a recent acquisition, struggling Canadian slot-machine maker Bluberi Gaming Technologies Inc, was worth about C$110 million. In footnotes, it said that figure was based largely on an agreement for Bluberi to supply 7,000 slot machines to a “commonly controlled enterprise.” Callidus did not identify that enterprise. But it appears to be Gateway Casinos, which fits the description in a recent Callidus earnings report of a “large diversified gaming company in Canada that is controlled in common with ... Catalyst.” Catalyst did not respond to requests for comment. Such an order is large for Bluberi, a small company that recently emerged from bankruptcy. Bluberi has about 1,000 machines in use today, according to a third-quarter 2017 ranking by industry consultants Eilers & Krejcik Gaming LLC. The top three companies have nearly 40,000 each. Gateway operates 9,500 slot machines, according to its website. Stephen Casey, a lawyer and accountant in New York with private equity experience, reviewed Callidus’s Bluberi holding for Reuters and called it “a very aggressive valuation based on a related-party order and some pretty speculative assumptions.” The risks, Casey said, include whether Bluberi’s casino clients can get the required regulatory approvals for expansion, and whether Bluberi is able to produce all the machines required. Callidus acknowledged both of those risks in earnings reports last year. Bluberi did not respond to requests for comment. Callidus’s Bluberi valuation, now at C$113 million, is based on a potential sale using an accounting method the company calls “yield enhancement,” which is not recognized under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). In a May shareholder report, Callidus said it would give greater prominence to calculations based on IFRS in its public disclosures in response to an Ontario Securities Commission review of its financial reporting. The OSC declined to comment. Catalyst has said it would like to find a buyer to take Callidus private again, suggesting in a press release last year a price of C$18 to C$22 a share. The stock now trades around C$7, down more than 60 percent over the past 12 months. Callidus said in October 2016 that it had hired Goldman, Sachs & Co to handle a sale process that would be completed by June 2017. Goldman declined to comment. No buyer has yet emerged. (For graphic on Catalyst and its peers, click http://tmsnrt.rs/2BEFznj) (Edited by Carmel Crimmins and John Blanton)

Yahoo Finance

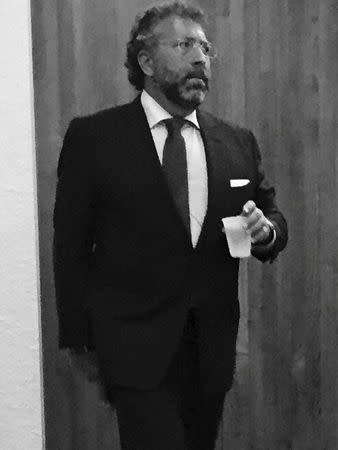

Yahoo Finance