Robots and AI are taking over factory floors, but manufacturing still needs the human touch

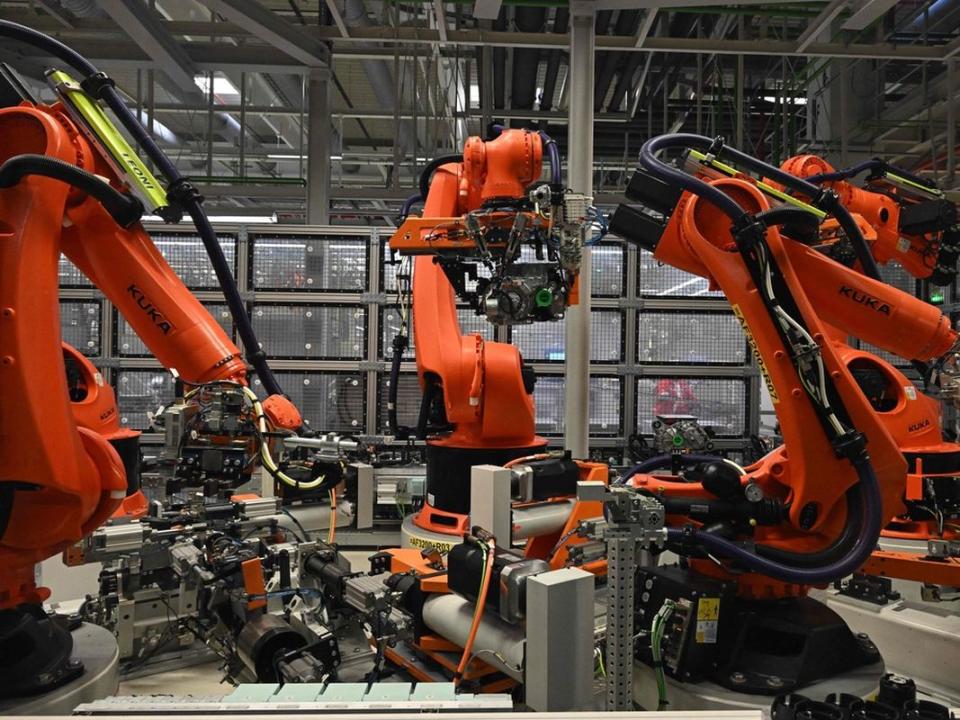

At a factory in LaSalle, Que., a series of robotic arms move swiftly and elegantly, twisting and turning as they assemble battery modules before ultrasonically welding them into place.

They’re helping to manufacture the world’s first electric watercraft and snowmobiles, pioneered by Taiga Motors Corp.

But the robots aren’t doing it on their own. On Taiga’s factory floor, human beings are present at every step, overseeing the automated work and stepping in when issues come up. Humans also assemble certain parts, arrange complicated wiring and operate machinery.

While many fear that automation and artificial intelligence will lead to a workerless future, Taiga’s operations offer a glimpse into the more likely reality: a revolution in manufacturing that eventually sees humans and robots interacting seamlessly on production lines and factory floors.

“Nowadays, because of how the technology is evolving and the prevalence of artificial intelligence, we are beginning to see robots that are smaller, more intelligent, powered by AI, working side-by-side with humans,” said William Melek, a professor in the department of mechanical and mechatronics engineering at the University of Waterloo and director of two robotics hubs.

When it comes to the use of technology on factory floors, the pace of advancement has been “staggering,” Melek said.

The global industrial automation market is growing, and is expected to reach US$441.7 billion by 2030. Soon, we’ll enter the fifth Industrial Revolution, he said, which will be characterized by “harmonious human-machine collaborations.”

Many people have mixed feelings toward robots. Some are convinced robots are out to take their jobs, but Melek frames the struggle differently.

“I think humans utilizing automation and AI will take away jobs from humans who are not (utilizing automation),” he said.

When used correctly, AI and automation can improve the lives of operators, engineers and technicians, said Yusuf Altintas, a pioneering engineer and head of the University of British Columbia’s Manufacturing Automation Laboratory.

I think humans utilizing automation and AI will take away jobs from humans who are not (utilizing automation)

William Melek

Automation is best for quality control or unsavoury tasks that are either too repetitive, dangerous, or just too boring for a human, he said. AI is also adept at predicting how a mechanical part will perform throughout its lifetime, and when it is most likely to fail.

Automation and digitization underpin Taiga’s manufacturing operations. The robotic arms are connected by an artificial intelligence-backed software, so if there’s an issue anywhere on the line, the engineers and technicians can go back through the digital track record and figure out exactly where the problem occurred.

This digital replica of the manufacturing system is called a “digital twin.”

Amazon Web Services defines digital twin technology as “a virtual model of a physical object (that) spans the object’s life cycle and uses real-time data sent from sensors on the object to simulate the behaviour and monitor operations.”

In other words, a manufacturer digitally models an entire production chain, from material design, to product design to testing to assembly to creation to delivery to the consumer to forecasting the problems throughout the life-cycle of a part and how it should be repaired, Altintas explained.

“(Manufacturers) are trying to model all of these steps digitally now,” he said, “but I think it will be established within the next 10, 15 years.”

Despite the growing prevalence of robots and automated processes, humans must remain at the centre of manufacturing operations, Melek said, because robots lack one thing that comes naturally to human beings: common sense.

Imagine that a harness is about to give way on a factor floor, potentially dropping a heavy part on a worker, he said; a robot might not register what is happening immediately, but a human could quickly perceive that something is amiss.

There are also some tasks that even the most advanced robots will struggle to do. For example, at Taiga, humans manually snake wires through the base of the watercraft.

This kind of intuitive process would be extremely difficult to automate, said Sam Bruneau, chief executive and co-founder of Taiga, because the arrangement of the wires differs based on the vehicle’s configuration.

“You can route a cable many different ways,” Bruneau said. “So for that, humans are very efficient because they can easily manipulate in three dimensions with no training.”

Training is a crucial step when it comes to any robotic process, Bruneau said.

“The robot will say, ‘Hey, is this OK or not?’ And then you say, ‘No, this is OK. This is not OK.’ So it gets trained that way,” he said. “There’s a lot of human intervention.”

Without proper training, the robots could put workers at risk.

“To create a safe environment, the robot has to have a certain level of sensing ability and perception,” Melek said. “Understanding the human that is working in close proximity with the robot, understanding human intent, understanding human gestures, understanding human speech, so that the robot understands what the human wants it to do and is able to oblige.”

Though it is working seamlessly now, Taiga’s automated system took a lot of work to put together, Bruneau said.

“We are very proud of the progress we’ve made in the few past months,” he told investors on a Nov. 13 call. “There’s a lot of challenges up front in setting this all up. It took a bit longer than we wanted to get producing.”

They’ve learned a great deal in the process, though. In order to work, the automation had to be “targeted,” he said. A blanket solution simply would not have cut it. Those who try to automate everything don’t get the efficiencies they’re looking for, he said.

As artificial intelligence and automation becomes increasingly commonplace on manufacturing factory floors, companies will have to make crucial strategic choices on when to use humans and when to use robots to maximize efficiency, Altintas said.

“They have to do their homework first,” he said. “(They have to) define what they expect, what they want from automation.”

• Email: mcoulton@postmedia.com

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance