Novel envisions American economic apocalypse

China has surpassed America as the world’s leading superpower. The dollar crashes, replaced by a form of currency called the “bancor,” controlled by the “New IMF.” All US Treasury bills and bonds are declared null and void. The government calls in all gold reserves, and sends agents around to search homes and seize any hidden gold jewelry. No citizen may leave America with more than $100 in cash. Inflation goes through the roof; cabbage goes up to $30 per head. Once-wealthy New Yorkers can no longer afford toilet paper.

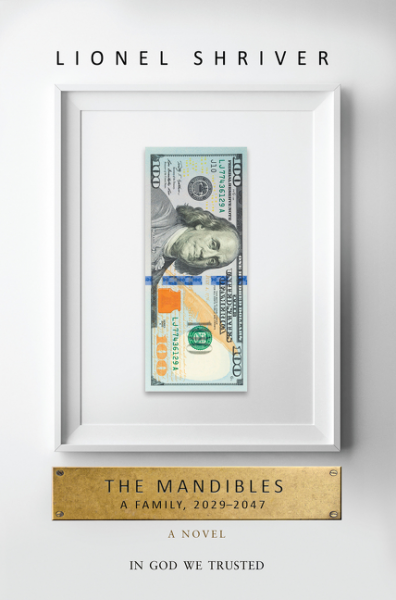

Luckily, it’s all fiction—for now. It’s the premise of Lionel Shriver’s new novel “The Mandibles,” which focuses on the fortunes of one American family from 2029 to 2047.

But it is plausible fiction, which is what makes the novel so scary and compelling. In Shriver’s dystopian near-future, Mexico even builds a wall along its US border—to keep Americans out.

Donald Trump had not yet announced his presidential campaign when Shriver wrote the book, which came out in June, but she tells Yahoo Finance, “It seems to me that he’s copying me. I think he got hold of an early proof.”

“The Mandibles” starts out in the midst of an economic crisis that is already worse than 2008. It quickly gets much worse, and spins out of control so far that three different nuclear families (all part of the same larger Mandible clan) must squeeze into a one-bedroom apartment in Bushwick, Brooklyn. In lieu of toilet paper, they must use rags (torn from clothing) soaked in vinegar. The New York Times shuts down; old editions become kindling for fire. One of the teenagers in the family starts prostituting herself. Her father takes issue with the decision, but not for the reason you’d think: “Too much competition.”

Is all of this plausible? “I’m afraid that it is,” says Shriver. “Writing about economics has become, not just entertaining, but positively apocalyptic.”

Shriver’s novels often tackle major social issues. “We Need to Talk About Kevin” was about a school shooting. “So Much For That” was about the American healthcare system. Because of these topics, Shriver is no stranger to controversy. And this month, she caused a new one with a keynote address she made at the Brisbane Writers Festival in Australia.

At the festival, Shriver (wearing a sombrero, a reference to a recent scandal at Bowdoin College) defended the right of writers to write in the voices of characters belonging to different cultural groups from the writer, whether it be different race, ethnicity, religion, sexual preference—anything.

The popular term these days for such practice is “cultural appropriation,” but Shriver says she rejects that term, since it inherently implies that the practice is wrong. Nonetheless, the festival organized a “rebuttal” after her speech; Yassmin Abdel-Magied, a writer in Australia who is of Egyptian and Sudanese descent, walked out and wrote a Medium post criticizing Shriver; The New Yorker wrote that her speech, “enacted what it was trying to rebuke—that is, it framed the people she disagreed with as culturally dangerous.”

One week after the festival, with think-piece articles still coming out about the dust-up, Shriver responded. “Taken to its end point,” she says on the idea of cultural appropriation, “you can’t even eat at an ethnic restaurant, because that’s their food, that’s not for you.”

Writers of fiction, Shriver argues, “have to be able to write from the perspective of people who are different from themselves, or there is no fiction, all you’ve got is memoir. I definitely don’t want to write only about myself for my entire life, and I’m confident that my readership doesn’t want to just hear about a 5’2” white straight woman from North Carolina with bad knees. I think the best of fiction is the impulse toward understanding other people and trying to put yourself in their heads.”

In Shriver’s imagining of 2029, Latinos are the dominant ethnic group (the president is one too) and are called “Lats.” The eldest Mandible (“Great GrandMan”) is re-married to a black woman who now has dementia, and he leads her around on a leash. The novelist Ken Kalfus, writing at The Washington Post, accused the novel of multiple “racist characterizations.” But Shriver says, “The whole thing of ring-fencing cultures and races and experiences, like those of the disabled or the transgendered or I don’t care what, and saying that only those people can write about their experience, I think that’s a terrible mistake.”

Regardless of the controversy, and although some stretches of Shriver’s novel are dry and joyless, “The Mandibles” is smart, richly researched, provocative, and great fun.

The reason a scary dystopia like this is fun to read is perfectly captured by a very meta exchange between a father and daughter in the book. The father, Lowell, is telling his daughter, Savannah (the one who becomes a prostitute), about science fiction novels like “2001: A Space Odyssey” and “1984.” He says, “Plots set in the future are about what people fear in the present. They’re not about the future at all… Writers and filmmakers keep predicting that everything’s going to fall apart. It’s almost funny.”

Shriver’s novel gets too deadly serious to be funny, but it’s still fun, and fascinating. And as Shriver says, “The whole form of the dystopic novel is to be able to explore your fears, but within a context of total safety. You can read all this stuff happening, and it seems as if it could happen tomorrow, but then you can put the book down, and pour yourself another drink.”

—

Daniel Roberts is a writer at Yahoo Finance, covering sports business and technology. He also writes often about interesting new books. Follow him on Twitter at @readDanwrite.

Read more:

Former Sports Illustrated editor recalls publishing’s good old days in new book

New book explores where big banks stand on blockchain

New book on NCAA makes the case for college athletes to get paid

BuzzFeed reorganizes its media business for the second time this year

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance