Norway's tax-the-rich drive provokes widening business backlash

(Bloomberg) — Norway’s planned clampdown on the nation’s wealthiest citizens is provoking a backlash from entrepreneurs who warn the measure will just worsen the economy’s heavy dependence on oil and gas.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Wells Fargo Fires Over a Dozen for ‘Simulation of Keyboard Activity’

Tesla Investors Back Musk’s $56 Billion Pay Deal, Texas Move

Apple to ‘Pay’ OpenAI for ChatGPT Through Distribution, Not Cash

Hunter Biden Was Convicted. His Dad’s Reaction Was Remarkable.

Tech Powers Stocks as Adobe Surges in Late Trading: Markets Wrap

The Labor-led government is poised to expand the scope of an exit tax on capital gains. The proposal, first revealed in March and due for parliamentary debate later this year, attempts to close a loophole exploited by an exodus of billionaires who have already moved to Switzerland to escape higher levies on their riches.

While aimed at the country’s wealthiest individuals, the potential impact is alarming a broader array of entrepreneurs and businesspeople, including startup chiefs such as Marit Rodevand, whose company, Strise AS, makes software to combat money laundering.

“Norway is a very state-controlled oil-and-gas economy,” she said in an interview at her office in central Oslo. “We really need new industries. The politicians should step back and think: this tax doesn’t make us competitive on the global scene.”

Rodevand, who started her first company developing software for the construction industry more than a decade ago, warns that the measure could force her to freeze hiring in Norway and seek staff in the UK because startups like hers use share options as a payment incentive.

Similarly, entrepreneur Johan Brand, co-founder of educational technology company Kahoot! AS, says he will “very likely” opt for the UK as the location for a strategy software business he previously wanted to set up in Norway. He laments that politicians and voters have forgotten that Norway was “a poor country with a very limited industry not that long ago.”

Such arguments expand on the existing clash of ideas between proponents of Norway’s typically Nordic aspiration for an egalitarian society, and those who claim such policies penalize success.

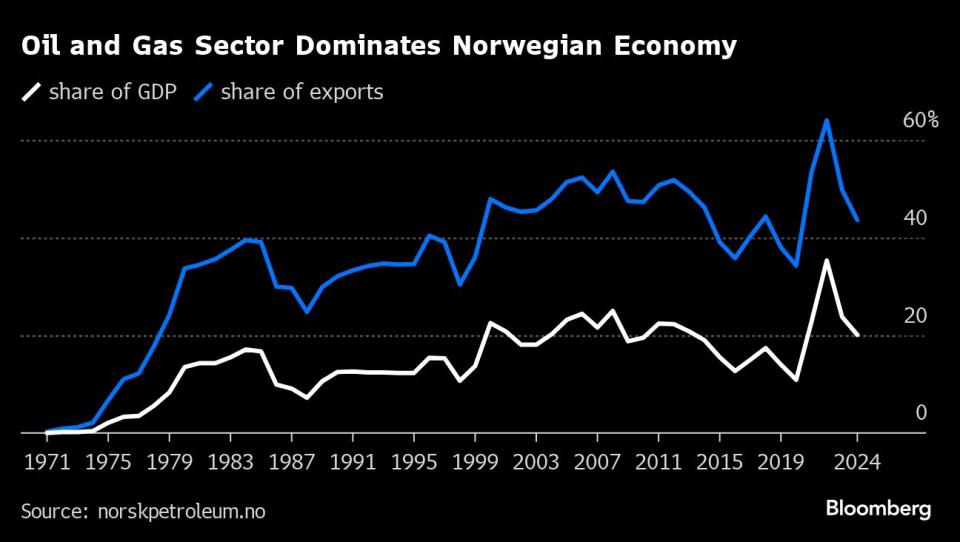

Instead, they question if the country is serious in its aim to diversify from a longstanding dependence on the petroleum sector, which is seen contributing a fifth of gross domestic product this year and 44% of its exports.

The government proposal seeks to fortify the existing regime where an exit tax doesn’t apply until gains are realized in a sale. The change proposed in March — taxing unrealized gains — would apply to anyone emigrating since then. Starting from a threshold of 500,000 kroner ($46,901), the tax — at a rate of 37.8% — would have to be paid within 12 years of leaving, either as a lump sum or in interest-free installments.

While that’s already more onerous than before, the new rule wouldn’t allow for a reduction in the liability even if the asset in question falls in value after leaving Norway. So it would capture theoretical gains at the time of emigration — an onerous rule for employees at startups, given only a small share of them actually succeeds.

The measure threatens to disincentivize talent and capital, and incur losses for value creation that far exceed any money that it raises, Anders Mjaset, the head of the Norwegian Alliance for Startup and Tech, said last month. Finance ministry calculations show an initial annual gain of 100 million kroner, growing to about 1.2 billion kroner in 12 years time.

In its own response, the country’s employers’ organization, NHO, lamented the plan’s impact on competitiveness, saying that it could affect “Norway’s ability to attract expertise and risk capital that is necessary for innovation and restructuring,” while citing the risk of “a further increase in emigration, which in turn will weaken the tax base.”

But the government of Premier Jonas Gahr Store isn’t flinching over a policy aimed at creating a more equal society, an ambition that the country can claim some success with.

The richest 1% of Norwegians held 22% of net wealth in 2022, according to Statistics Norway. That compares with 34% in the US, 30% in Germany and 21% in the UK, based on the Global Wealth Report by the UBS.

The finance ministry, in its notice inviting feedback, said that the plan aligns with a growing international focus on “more effective taxation of so-called High Net Worth Individuals.” The 12-year limit provides “a generous grace period which reduces the liquidity burden for taxpayers and facilitates mobility over national borders,” it said.

The measure was originally proposed in 2022 by the Socialist Left party, which is allied with the minority coalition though not officially part of it. It cited the example of Germany, whose own exit tax has a shorter deadline for payment in annual installments, at seven years.

Kari Elisabeth Kaski, a senior lawmaker from that group, said she isn’t worried “at all” about the plan hampering the appeal of Norway, which “is very well run, both for businesses and startups.”

The country’s entrepreneurs aren’t so sure. Norway’s startup ecosystem slid to 25th place globally, down two places from last year, trailing Nordic peers apart from Iceland, according to a ranking provided by StartupBlink.

While they worry about the impact on their own businesses, the argument about Norway’s reliance on petroleum does hit home in a region whose relatively small countries have often built their prosperity on out-sized industries or even single companies, such as Nokia Oyj in Finland’s case, or more recently, Denmark’s Novo Nordisk A/S.

“Oil wealth has changed our behavior,” Brand at Kahoot! said in an interview. “What happens when we know the oil business is going to go down? We have no alternative.”

While Norway’s dependence on hydrocarbons has been a huge boon, it is also an acknowledged weakness. Budget documents observe that fiscal policy is “more vulnerable” to reductions in the value of its sovereign wealth fund that invests the country’s oil and gas revenue.

In a government white paper in 2021, officials wrote that “it is necessary to diversify the Norwegian economy to maintain welfare growth,” adding “a highly skilled labour force is of decisive importance for taking on board international innovations and for creating our own innovations.”

For now, the exit tax proposal looks likely to become law. How long it will stay on the statute books is less certain however: The Conservative opposition has indicated that it would undo the measure if it defeats the ruling Labor and Center parties in Norway’s election in September 2025 — an outcome that polls currently indicate is possible.

In the meantime, Rodevand at Strise is resolved to keep arguing her case.

“There is something really great about Norway,” she said. “We have the ingredients to foster a very innovative ecosystem, but then I think the ground rules should at least be that we’re on the same playing field with the others.”

—With assistance from Heidi Taksdal Skjeseth.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Israeli Scientists Are Shunned by Universities Over the Gaza War

Grieving Families Blame Panera’s Charged Lemonade for Leaving a Deadly Legacy

The World’s Most Online Male Gymnast Prepares for the Paris Olympics

China’s Economic Powerhouse Is Feeling the Brunt of Its Slowdown

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance