Louisville got a lot of money ($111 million, to be precise) from the state budget. Why didn’t Lexington?

It’s Kentucky Derby Week, which means all eyes will be on Louisville leading up to Saturday’s Run for the Roses.

But a Herald-Leader analysis of recent spending measures approved by the General Assembly revealed lawmakers didn’t wait until the first Saturday of May to look favorably toward Kentucky’s largest city: Louisville’s city government earned more than 11 times more money than Lexington’s in the state’s massive one-time spending bill.

And the biggest winner: Louisville’s downtown, which landed $100 million to revitalize its troubled core.

Looking strictly at an apples-to-apples comparison, Lexington tallied $10 million.

Some legislators and Fayette County officials point to math to defend the considerable difference in spending for Louisville vs. Lexington.

First off, Louisville’s population of 772,000 is almost 2.5 times more than Lexington’s 320,000 population.

Others underscore the fact that Lexington and Louisville are very different cities, and the view from Frankfort — which is run by a GOP majority that skews rural and suburban — varies.

“I think there’s an understanding that, for a variety of reasons, Louisville is in a little bit more of a crisis situation than Lexington,” Senate GOP Floor Leader Damon Thayer told the Herald-Leader.

Lexington’s problems with crime aren’t as severe or as publicized as Louisville’s, whose 2023 homicide rate was more than twice Lexington’s per capita.

The downtown is more visibly thriving, too, with new businesses and a major park incoming; it’s also largely avoided a “war on Louisville”-style narrative in its dealings with Frankfort.

These and many other factors may help explain the Kentucky General Assembly’s spending decisions this year, as it had money to spend in a way it hadn’t during budget session years since the 2008 recession.

The legislature spent more than $2.7 billion on one-time appropriations alone, on top of the $30 billion-plus biennial General Fund budget.

The comparison between Lexington and Louisville gets a little more complicated, and shifts slightly more in Lexington’s favor, when taking into consideration other investments.

Some questions must be asked:

Does the $36 million backing major renovations at the Kentucky Horse Park, a state-run operation that straddles the line between Fayette and Scott counties, count for Fayette County?

Does all $20 million invested in Kentuckiana Works, a regional workforce effort headquartered in Louisville but serving six other counties, count towards Jefferson County’s total?

Further, the state’s flagship university, the University of Kentucky, brings in just under twice as much from the state General Fund as the University of Louisville — about $685 million to $374 million. How should that be considered?

All of this is up to interpretation and not as clean of a comparison as Louisville Metro Government’s $111 million compared to Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government’s $10 million in the one-time spending bill.

Greenberg & Gorton

Some told the Herald-Leader that leadership in the two cities play a factor with legislators in Frankfort.

One lawmaker said Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg’s tenacity on budget issues was “the biggest difference” between Jefferson and Fayette counties.

“Our mayor was in Frankfort working very hard. I’ve never even seen your mayor,” House GOP Whip Jason Nemes, R-Middletown, said of Lexington Mayor Linda Gorton.

“That doesn’t mean that she wasn’t in Frankfort working, but I didn’t see her. Mayor Greenberg was in Frankfort frequently.”

Unlike Nemes, Greenberg is a Democrat.

“I mean, I’m not in the business of going out and praising (Louisville Mayor Craig Greenberg) him high and wide,” Nemes said. “I didn’t vote for him, and if he were in my district he wouldn’t vote for me, (but) he worked it.”

Lexington Mayor Linda Gorton, for her part, said that there was no big-ticket item the city asked for that it did not receive in the state spending budget.

The mayor stressed Fayette County also got help from the state legislature for expansion projects at the Blue Grass Airport to the tune of $9 million.

She said she personally lobbied for a $10 million allocation to widen a part of Georgetown Road and $1.8 million for designs for a new connector between Polo Club and Sir Barton Way in the city’s bustling Hamburg area.

“I was over lobbying for those road projects because those are huge and we can’t build them by ourselves,” Gorton said. “... When we started looking at all the appropriations we got, it’s pretty big.”

Louisville’s government also outspent Lexington by a considerable margin on official lobbying efforts.

According to records provided to the Herald-Leader, Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government has a 7-month contract with a lobbyist for $15,000 ending this June; Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission records show $6,000 spent over the first three months of the legislative session.

Combined, Louisville Metro Government and its sewer division spent almost $47,000 during the first three months of session.

Thayer attributed Louisville’s influx of funds to the work of Nemes, Adams and Greenberg. Thayer said the GOP-led legislature likes Greenberg much more than his predecessor Greg Fischer, a Democrat who began his 12-year tenure as mayor when his own party had control of the House and the Governor’s Mansion.

Senate President Robert Stivers, R-Manchester, said that he’d spoken more with Greenberg during his short tenure than he did with Fischer through his 12 years.

“The fact of the matter is the bar was pretty low,” Thayer said. “I mean, I don’t know anybody that likes Greg Fischer.

“It wouldn’t take much for us to like the new mayor better, and he’s a decent, easier guy to work with.”

Greenberg’s staff said he visited Frankfort to meet with legislators four times during the session and made daily phone calls regarding state projects.

“My approach is that we’re all people, we all share common goals, so let’s talk to one another and find areas that we can work on together,” Greenberg said in an interview.

“I’ve met some really wonderful people, as a result of working to build relationships, and I think that’s the way that government should work.”

Both the House Speaker and Senate President held a press conference this week in Louisville highlighting the funds provided to the area. They praised Greenberg’s efforts.

Sen. Amanda Mays Bledsoe, R-Lexington, serves as vice chair of the Senate Appropriations & Revenue Committee. She framed this budget session as “Louisville’s shot.”

“This was Louisville’s shot. They’re getting a significant investment, and this is their shot to revitalize,” she said. “Now we wait and see.”

Lexington’s success

When it comes to getting money from Frankfort, Lexington may be a victim of its own success.

At least that’s what Bledsoe indicated.

“I think Lexington has done a very good job of taking care of its community,” Bledsoe said. “We have needs, certainly, but I don’t have a good answer for you. We just haven’t done that.

“We haven’t been the community that goes to Frankfort a lot and asks for help.”

Indeed, Lexington has gotten help from other sources.

Gorton has touted millions of dollars in federal money in recent years for key road projects and economic development projects like the $10 million direct allocation from the federal government to pay for infrastructure at a nearly 200-acre new business park off of Georgetown Road.

The city is also benefiting from private funds. Donors recently rounded up $39 million in funding for a public park downtown, adjacent to Rupp Arena.

Friends in high places

And a lot of how the money shakes out may depend on who’s in what post.

Former Lexington Democratic senator Ernesto Scorsone recalled the days of former senator Mike Moloney serving as Senate Appropriations & Revenue chair.

“When Lexington needed something, it could get it pretty easily,” he said.

Who the Senate A&R chair is still matters. McDaniel, for instance, shepherded a massive $135 million investment, partly in his district, to move Northern Kentucky University Chase School of Law to Covington.

Scorsone served as a House member, in the Senate and as Fayette circuit judge for more than a decade in each post, retiring as a judge in 2021. In Frankfort, he served through 12 budget cycles up until 2008.

He sees the budget in fairly simple terms.

“I’m not so sure that need is the driving force,” Scorsone said. “I would go to political clout as the driving force.”

Lexington’s last big push for state dollars, according to Bledsoe and Scorsone, came for renovations to downtown’s Central Bank Center and Rupp Arena, which were completed about 18 months ago.

During former mayor and current Transportation Cabinet Secretary Jim Gray’s tenure, the state provided $60 million in bond funds for the project after some drama between state and local governments.

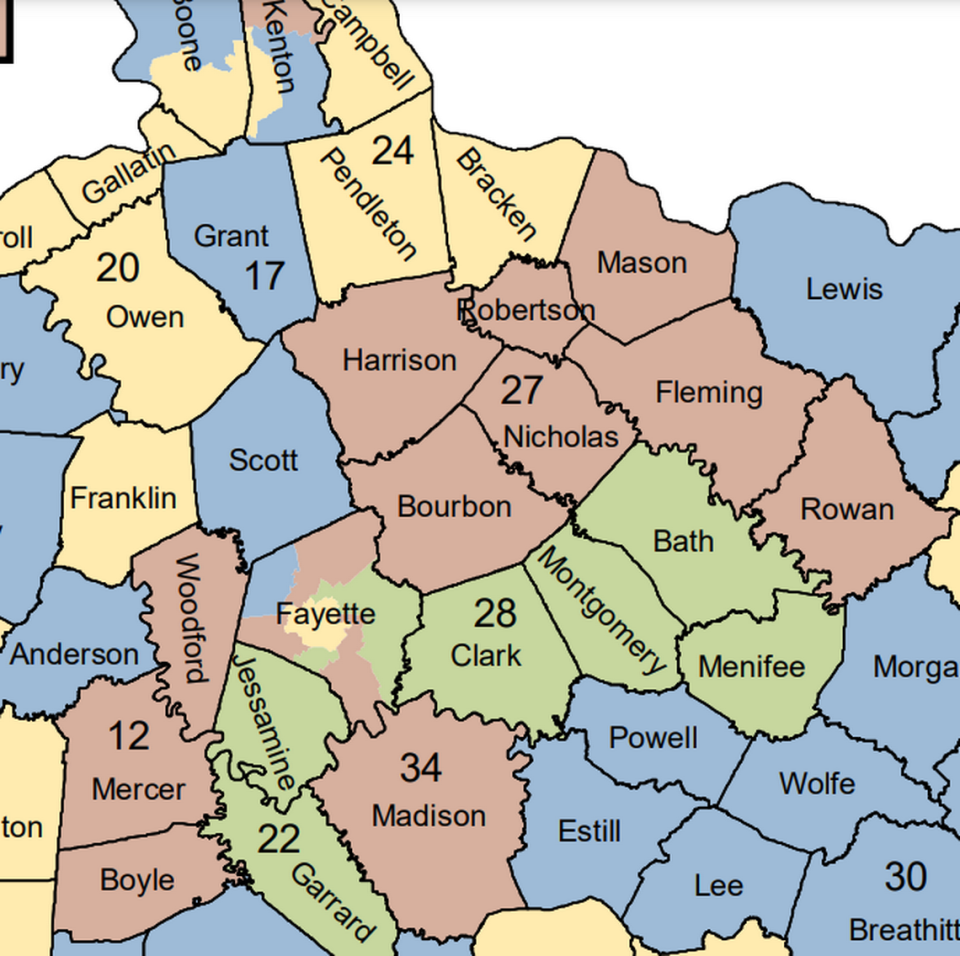

It could be soon that Lexington makes another big ask, Bledsoe said. Her assignment as A&R vice chair in her first term might indicate that Lexington will someday have one of its own in Senate majority leadership – however, she also represents Woodford, Mercer and Boyle counties, which together comprise the majority of her district’s population.

“It definitely helps Lexington for me to be in the position I’m in to be an advocate for Lexington and Central Kentucky,” Bledsoe said. “One of things I hope to do is to have a better, more thorough and comprehensive approach to meeting some of our best needs moving forward.”

As for major projects in Lexington’s future, a new city hall looms large and a new park on the banks of the Kentucky River.

Political lines could also play a role.

Jefferson County has two members of Republican leadership with House GOP Whip Jason Nemes and Senate Majority Caucus Chair Raque Adams in its boundaries — House Speaker David Osborne, R-Prospect, also lives in the Louisville metro area.

Meanwhile, one Fayette County senator whose district is entirely in the county: Sen. Reggie Thomas, D-Lexington.

Louisville has six such senators. Louisville-only House members also outnumber Lexington-only House members disproportionately – 15 to 5.

The Senate’s Fayette County map looks like a donut, with the hole being Thomas’ district. The outlying donut is split six ways between six Republican senators; Fayette Countians make up a minority of all those districts.

Thayer was asked about what effect this might have on Lexington’s needs in the summer of 2022, before Bledsoe was elected.

“None of us live in Lexington, but we live awfully close,” Thayer said.

“I’’m in Lexington all the time. I was here for dinner last night, I come to Keeneland all the time, I shop at Hamburg and in Fayette mall. I go eat at The Summit.

“I think most of us here spend a lot of time in this community, and we’re pretty aware and can talk pretty easily about about what it needs.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance