Larry King, talk-show titan who lit up worlds of politics and showbiz

A measure of Larry King’s impact on American television journalism was that for three decades, the easiest way of giving fictional cinematic politicians credibility was a scene in which they appeared on King’s CNN show.

His peak year was 1998, in which King, who has died aged 87, shared the big screen with John Travolta as a minimally disguised Bill Clinton in Primary Colors, Warren Beatty as a maverick Democrat senator in Bulworth, and Will Smith in the conspiracy surveillance thriller Enemy of the State.

Related: Larry King: 'The secret of my success? I'm dumb'

This visual shorthand depended on the perception in America – and, due to CNN’s reach, around the world – that a politician or political story really mattered if they appeared on King’s show. Proving this view in 2010 was that both the then incumbent American president (Barack Obama) and a recent two-term predecessor (Clinton) appeared on King’s final CNN show, the last in a sequence of appearances with him on the route from candidate to commander-in-chief.

The heart of the brand was 7,445 editions of Larry King Live on CNN over 25 years, featuring guests – or, if it was a president, movie star or bestselling writer, only one – in conversation punctuated by questions from viewers.

Essentially, it was a TV version of a radio phone-in, developed from a three-hour afternoon wireless slot, The Larry King Show, which started on the Mutual Broadcasting System in 1978 and continued alongside his higher-profile screen franchise until 1994.

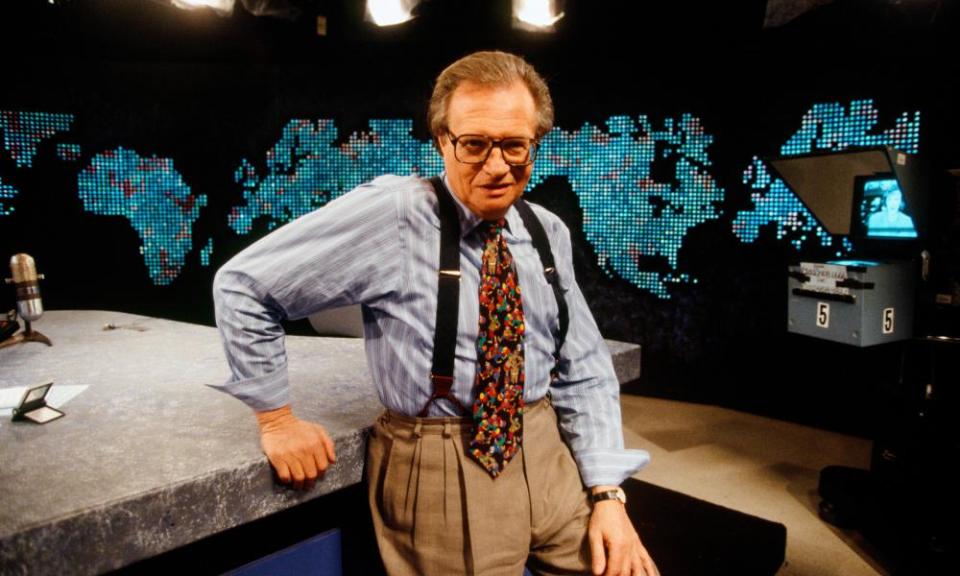

Such was the format overlap that King sat side-on at his television desk (TV presenters normally talk out-front) and the conversational space was divided by an old-fashioned radio mic, like a big silver metal tongue. This audio prop was, counter-intuitively, visual, as was King’s other screen signature: Wall Street-style braces (in American usage, suspenders) usually worn over a block-colour shirt.

Four hours of radio and TV on most days was a brutal workload, eased by King’s declared policy of never reading the books a majority of guests were there to plug. Justifying this low-research approach, the host said he was starting from the same position as the viewers, open-minded and wanting to be persuaded.

Questions that could be as broad as “Why’d you write this?” or “What’s your favourite story in the book?” might be sniffed at by more forensic inquisitors, but King was an intelligent and well-informed guy, and the value came from his “Why’d ya do that?”, “Don’t ya think that?” follow-ups. Unlike some interviewers, he listened to the answers. A favourite tactic, as his backlist of big names thickened, was to quote what Celebrity A had told him and wonder if Celebrity B agreed. Only made possible by the pulling power of his programme, it could be very illuminating.

In a career arc matched by few of his famous guests – except, perhaps, Donald Trump and Joe Biden – King’s major achievements came in the later part of his life. Born in 1933, he was until late middle-age a minor regional broadcaster in Florida. Born Lawrence Ziegler in Brooklyn, he was persuaded, as a young radio announcer in Miami, to change a surname considered by the racist judgment of media at the time too Jewish for mainstream ears. The broadcaster claimed he picked his new identity on whim, from a Miami Herald open in the studio to an ad for King’s Liquor Store, though as a man of marked self-esteem, he may have enjoyed the regal ring of his nom-de-mic.

His new name was not really made until, when he was 52, he started Larry King Live. His first guest was Mario Cuomo, governor of New York and a perpetual potential presidential candidate, who set the tone for a serious political talk-show.

At the time, cable TV was seen as a dribbling tributary of the mainstream media, CNN initially ridiculed as “Chicken Noodle News”. But the network’s visibility through the Gulf War of 1990, the first conflict fought live on TV, brought King attention and audiences maximised by CNN International being the English-language TV option in most hotels around the world.

King’s nearest equivalent in broadcasting history is Sir David Frost (1939-2013). Though English and American by birth, Frost and King each achieved an unusually international televisual identity. In another connection, a studio “sit down” with either man became a rite of passage for any politician seeking the US presidency.

King will be remembered as the first superstar American broadcaster to emerge outside the traditional networks

Like Frost, who he somewhat facially resembled, King was fascinated by fame, becoming so well-known himself by interviewing political and showbiz stars that his studio became the destination for younger celebrities. Both men benefited from the fact that an interviewee was likely to be so pleased with the respectful reception they were given on first appearance that they would willingly, and frequently, repeat it.

A mark of the status of Larry King Live among the US elite came in 2004, when former President Clinton dialled in to the show from his hospital bed shortly before coronary bypass surgery, which King himself had received. In a subsequent joint appearance, Clinton briefly panicked when King introduced him as a “member of the Zipper Club”, seemingly fearing a sexual reference to frequently opened trousers, rather than the image of the distinctive zip-like scar of invasive cardiac procedures.

If it had been the other Zipper Club, King might qualify. Maritally, the broadcaster outdid another King – Henry VIII – by achieving eight weddings, all ending in divorce, although involving only only seven women, as one went through both ceremonies twice. King Larry’s spouses also came to kinder ends than those who married Henry Tudor, various settlements encouraging him to continue a TV career until his death. Since 2012, he had fronted Politicking With Larry King, a weekly talk show on Hula, Ora and RT America.

This turbulent private life meant the presenter was only periodically content, and he also suffered the extreme parental experience of being pre-deceased by two of his five children.

The numerous fictional cameos as himself, of which the 1998 trio was the apotheosis, had begun with a pre-CNN appearance in Ghostbusters in 1984, then the late-20th-century celebrity badge of voicing a cartoon avatar in The Simpsons, in episodes in 1991 and 1994.

Related: Kenneth Branagh to play Boris Johnson in TV drama about Covid crisis

The most amusing of his Hollywood appearances was in Dave (1994), a sharp comedy with Kevin Kline as a presidential lookalike who takes over when the real incumbent is incapacitated. Oliver Stone, sending up his reputation as a conspiracy theorist, appears in a spoof Larry King Live segment, presenting video evidence that the president has recently been switched for an imposter. King tells him he has really gone too far this time.

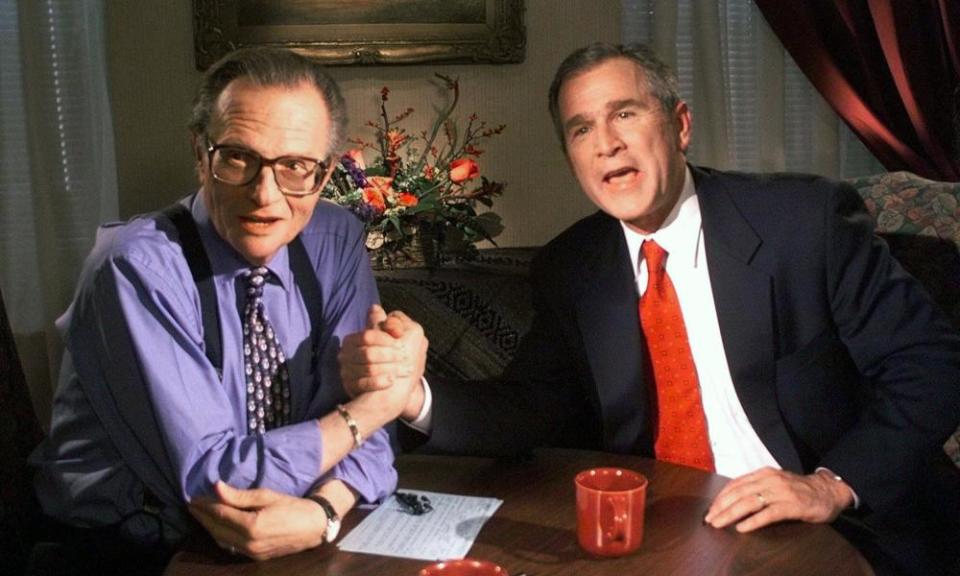

Whether or not King noticed, this was slightly double-edged, as it showed him promoting a Washington-friendly message that misses the real story, which was broadly the allegation of his detractors. The fact it was Obama and Clinton who presided over King’s CNN valediction was also seen by some as politically revealing, and although the Bushes and (in his reality TV and real estate days) Trump were willing King guests, it is reasonable to see Larry King Live and CNN as part of the broadcasting establishment that Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News set out to counter.

King, though, will be remembered as the first superstar American broadcaster to emerge outside the traditional networks, whose access to the stars of Washington politics and Hollywood showbiz greatly helped to illuminate those worlds.

He also had a curious, and accidental, influence on British broadcasting. His replacement on CNN was Piers Morgan, whose cancellation returned him to the UK, where his interviews on ITV’s Good Morning Britain with ministers dealing with the Covid crisis have represented the most sustained opposition to Boris Johnson’s government.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance