Kevin Carmichael: Why Tiff Macklem is willing to risk a recession to crush inflation

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem might be struggling to convince the broader public that inflation will return to two per cent ever again, but he’s managed to change the perception of what counts as a big interest-rate increase.

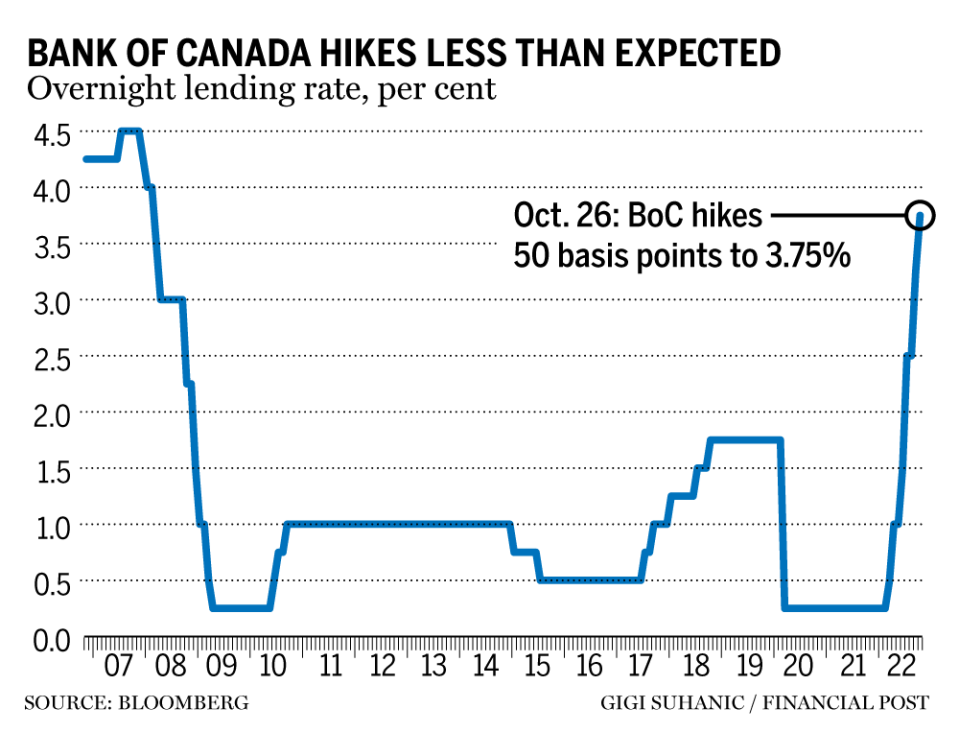

Macklem raised the benchmark interest rate a half-point on Oct. 26, lifting the target rate on which banks base their lending to 3.75 per cent. It was widely interpreted as a softening of the hard line the central bank had drawn on inflation.

Not so long ago, a half-point increase in borrowing costs would have been considered extraordinary, perhaps even a sign of panic.

After more than a decade of a low-for-longer approach to monetary policy, central bankers had become supersensitive about the damage they could cause by raising interest rates too quickly. It was received wisdom that anything greater than quarter-point tweaks could cause consumers to turtle, companies to bail on investment plans and investors to bolt to the sidelines.

That was then. The Bank of Canada’s previous interest-rate increase in September was three-quarters of a percentage point, and the one before that was a full percentage point. So, Macklem had to work this week to convince people that a half-point lift counted as a big deal. “This is a larger-than-normal step, a big step,” he told reporters when asked why he didn’t lift borrowing costs by three-quarters of a percentage point, which is what most currency traders and bond investors appeared to have been expecting.

Yields on two-year Canadian government debt dropped below four per cent for the first time in two weeks after the Bank of Canada pulled up short of market expectations, Bloomberg News reported. Meanwhile, the dollar was little changed, trading at about 74 cents U.S., which might reflect an assessment among traders that the Bank of Canada has joined the Reserve Bank of Australia in releasing the safety brake it had applied earlier this year to keep inflation from racing out of control.

“By hiking less than consensus forecast, the Bank of Canada’s policy decision is reinforcing the notion of a more generalized central bank pivot,” Mohamed El-Erian, the widely followed chief economic adviser at Allianz SE, said on Twitter, adding that by “pivot,” he meant market prices suggest investors see the pace of rate increases slowing, “as opposed to prior definitions of cut and pause.”

Indeed, Macklem was clear that a cut isn’t on the agenda, even though the Bank of Canada’s new economic outlook has growth stalling soon, if it hasn’t already. (The central bank predicts economic growth will slow to 0.5 per cent in the current quarter, and that gross domestic product will expand only 0.9 per cent in 2023.)

The central bank’s policy statement explicitly said “the policy rate will need to rise further,” because inflation is around seven per cent, way off the two-per-cent target. Most Bay Street and Wall Street economists reckon that means the benchmark rate is headed to at least four per cent, and maybe as high as 4.5 per cent before year-end. In the past, the Bank of Canada has opted to pause on its way to a new interest-rate setting to gather more information about how monetary policy is affecting the economy.

But Macklem appears unwilling to risk giving inflation any oxygen. At the press conference, he was asked whether the trajectory for interest rates from here would be “data dependent,” which would imply taking time to assess changing conditions, or whether considerations were simply about “pace and scale,” which would imply the only question on the table when policymakers next gather to set interest rates in December would be, how high?

“I would be closer to your second characterization,” he said. “I think we’ve been pretty clear. We think that rates need to go up further. This tightening phase will come to a close. We are getting closer to that point, but we’re not there yet.”

Those aren’t the words of a central banker interested in testing the lessons of the 1970s, when authorities let inflation run away from them. The Bank of Canada hedged by opting against another “very big step,” but crushing inflation remains the objective, even if that means tipping the economy into recession.

“People don’t necessarily believe inflation is coming down very quickly,” Jean-François Perrault, chief economist at the Bank of Nova Scotia, told the Financial Post’s Larysa Harapyn after the central bank’s policy announcement on Oct. 26. “So, how is it possible for the central bank to stop raising rates at 4.25 per cent when inflation is still above six per cent? That, I think, is the bigger challenge that they’ve got. How do they slow down, how do they stop raising rates when inflation is still so far away from their target?”

Macklem was asked about the 1970s this week. He said one of the main reasons inflation broke its tether back then was that there was no anchor because of the Richard Nixon administration’s decision to end the policy of linking the U.S. dollar to gold. It took the economics profession a couple of decades to settle on inflation targeting as a suitable replacement. Macklem, who was then an up-and-comer at the Canadian central bank, took part in some of the formative research.

The whole idea that the best way to execute monetary policy is targeting the year-over-year change in prices now faces its greatest test. Macklem emphatically said he has complete confidence in the Bank of Canada’s approach to monetary policy. That suggests he’s prepared to keep pushing interest rates higher until inflation breaks lower.

Bank of Canada opts for lower half-point hike, but says more to come

Bank of Canada swerves in 'game of chicken' with inflation: What economists say

FP Explains: Behind the Bank of Canada’s surprise 50 bps rate hike

Staying on the path he has chosen will be hard. Journalists who cover the Bank of Canada on a regular basis know monetary policy is resonating with the broader public when they find themselves competing with television reporters to ask questions at press conferences. All the networks had representatives at the press conference this week. Their questions all sounded something like this: Why are you killing the economy?

“We need to do what we have to do,” Macklem said. “We are trying to balance the risks on both sides.” He added that “Inflation is not going to fade away by itself.”

• Email: kcarmichael@postmedia.com | Twitter: carmichaelkevin

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance