Janis Joplin's Scrapbook Days & Summers Is an Intimate Self Portrait of a Rock Icon

Copyright © Fantality Corp. Photographed by Sam Faba

The notion of overnight rock stardom is little more than a compelling myth, but Janis Joplin certainly came close with her back-to-back performances at the Monterey Pop Festival in June of 1967. The 24-year-old wowed the crowd of hipster hippies and industry elites with an anguished airing of Big Mama Thornton's gutbucket R&B standard "Ball and Chain" while filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker's documentary cameras whirred. They captured what's become the most enduring image of the singer. She stomps. She growls. She shakes. She wails. Her face is contorted in agony as she punctuates lyrical accusations with a scornful thrust of her finger. When the song ends, she appears to emerge from a trance. As the rapturous applause echoes throughout the pavilion, her face erupts into an enormous grin. She retreats from the stage with a jubilant skip, a momentary display of ecstasy that shatters any illusions of her hardened blues mama persona.

"Janis nailed it and she knew it," her younger brother Michael tells PEOPLE. "That little dance is so sweet and innocent. It's like, 'I did it!' I love it because it makes her so human and approachable. Anyone can relate to it, even though she's a stranger from another decade who lived a different lifestyle. You can recognize that emotional moment. It's a beautiful thing."

This funny, warm and achingly fragile side of the vocal powerhouse is revealed in Janis Joplin: Days & Summers, a new book that showcases the scrapbook Joplin kept during the time she shot to fame between 1966 and 1968. Packed with rare photos, articles, artifacts, letters, and in-depth commentary from friends, family and fellow rock icons, the first page features a question handwritten in her distinctive script: "Doncha wanta see me be a star?" It's a line utterly devoid of hubris or ego. More than half a century after she put pen to paper, it's impossible not to detect a desire to make the reader proud, and prove herself more than a misfit from a Texas oil town.

Her notes can be charmingly childlike, brimming with wonder and amazement as she gleefully takes in every moment of her ascent to rock royalty. "Your first-born is really doing great in the music business," reads one letter to her family. "Did I tell you about all my reviews? Can I tell you again? This is all so exciting to me!"

The scrapbook is a touching self-portrait presented through mementos and small private moments, illustrating both how she saw herself and how she wanted to be seen. "You save stuff because it means something to you, and you can share it with somebody special," says Michael. "That's what this was for her." For years, he and sister Laura — executors of their elder sibling's estate — grappled with whether to keep the scrapbook private. "It's so personal," Michael admits. "It's Janis' handwriting and her notations and what she cut out of magazines with her little scissors in her apartment with her Elmer's glue. The personal aspect is one of the reasons we hadn't shared until now."

Copyright © Fantality Corp.

Scrapbooking was a tradition in the Joplin family, dating back to their years growing up in Port Arthur, Texas. Joplin was born on Jan. 19, 1943 to Seth, a Texaco engineer, and his wife Dorothy, who worked as a registrar at a local business college. Sister Laura arrived six years later, followed by brother Michael in 1953, when Joplin was 10.

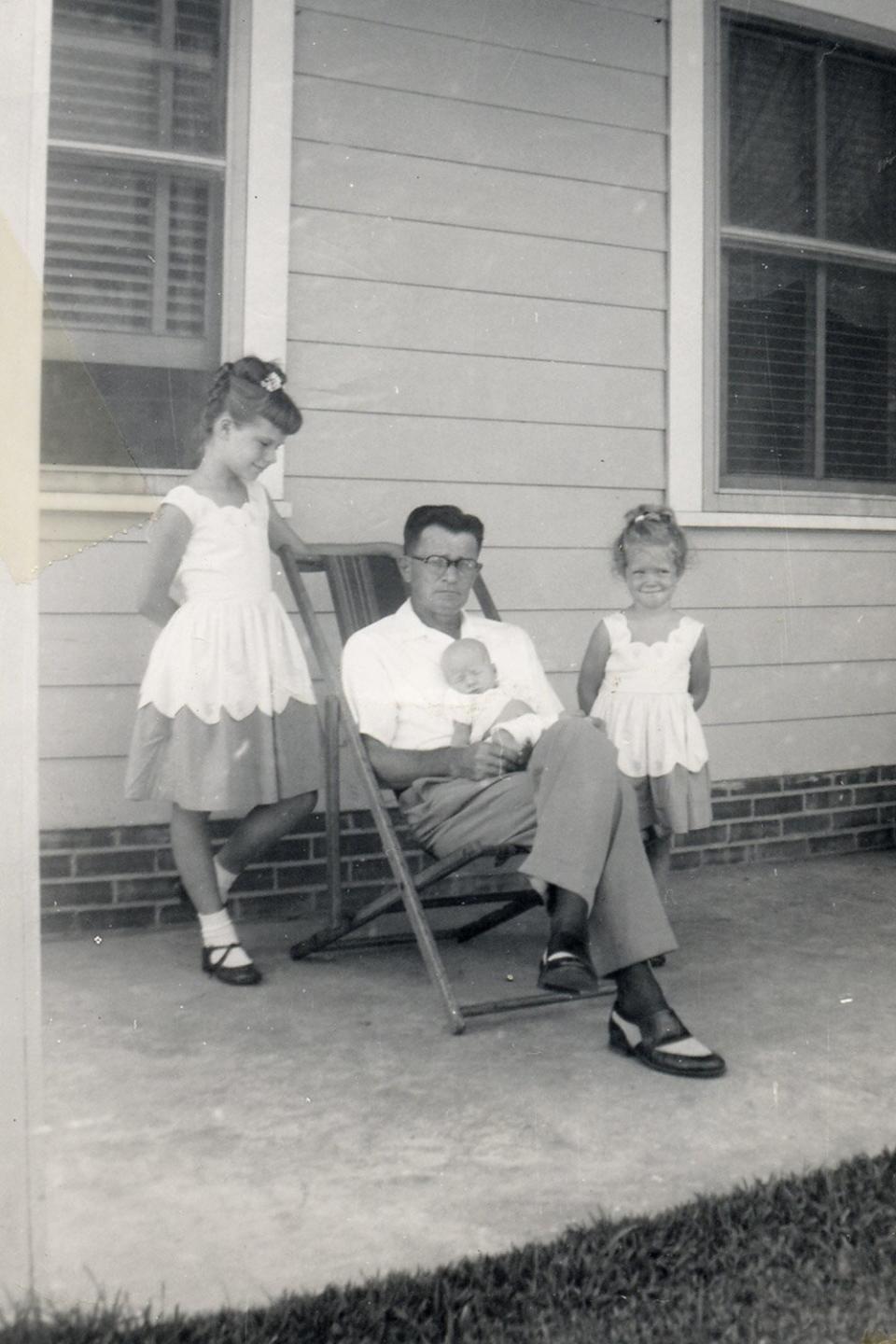

Copyright © Fantality Corp. Joplin and Laura in matching dresses made by their mother, Dorothy. Father Seth holds baby Michael.

It was a household that valued free-thinking and individuality — unusual in Eisenhower-era Texas. The parents led by example, integrating creativity into their daily lives. Seth designed and built playground equipment for the kids, while Dorothy sewed clothes for her brood and crafted needlepoint designs.

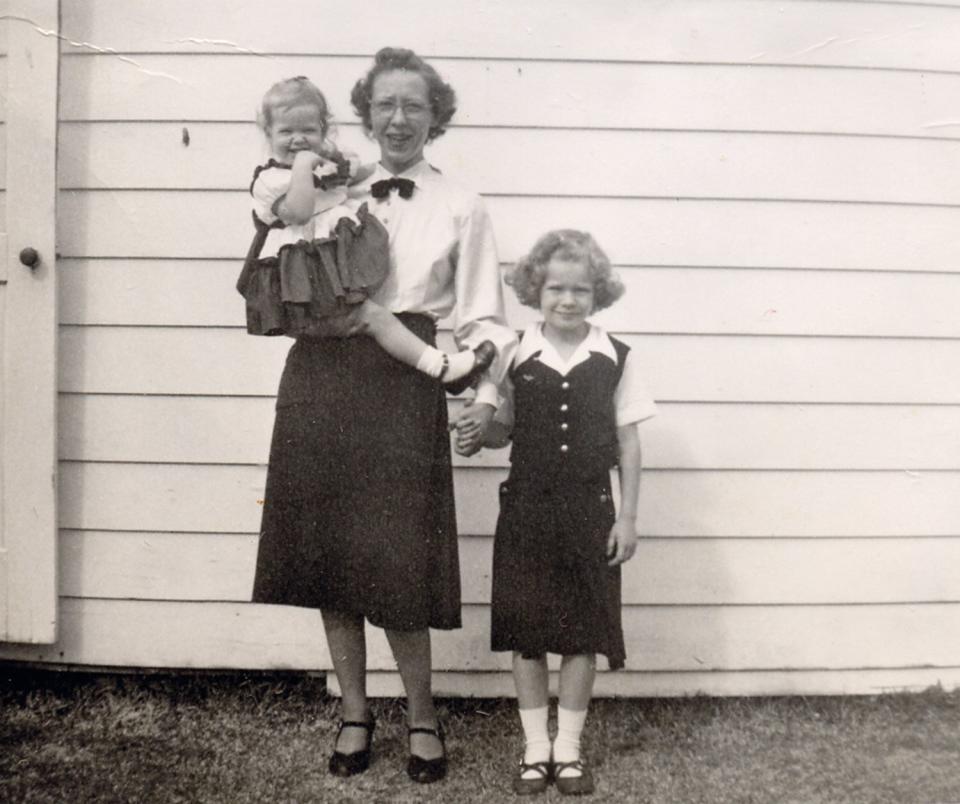

Copyright © Fantality Corp. Dorothy Joplin and her daughters, Laura (left) and Janis.

"Pop was a semi-frustrated artist who got a [day] job," Michael explains. "He had studied art. Mom was a semi-frustrated singer who had some surgery on her throat as a young woman and it hurt her vocal cords. They were cut off from their passion at a young age, so they allowed us to experiment." Instead of being given store-bought board games, the Joplin children were handed blank paper, crayons and pieces of wood and encouraged to make their own goals and rules. As adults, they approached life in much the same way.

A trip to the library was a weekly highlight. "That really anchored our family," Laura tells PEOPLE. "It was a real family value. We were given freedom in the library." Reading material was discussed each night at the dinner table. "Our parents felt it was important that you express yourself and that your ideas be ones that had meaning and value to you. They liked to teach, but they also listened. As a young person, that's pretty significant. It's how you grow. Knowing that someone listens is pretty significant. It means that you better take yourself seriously. That was an important lesson."

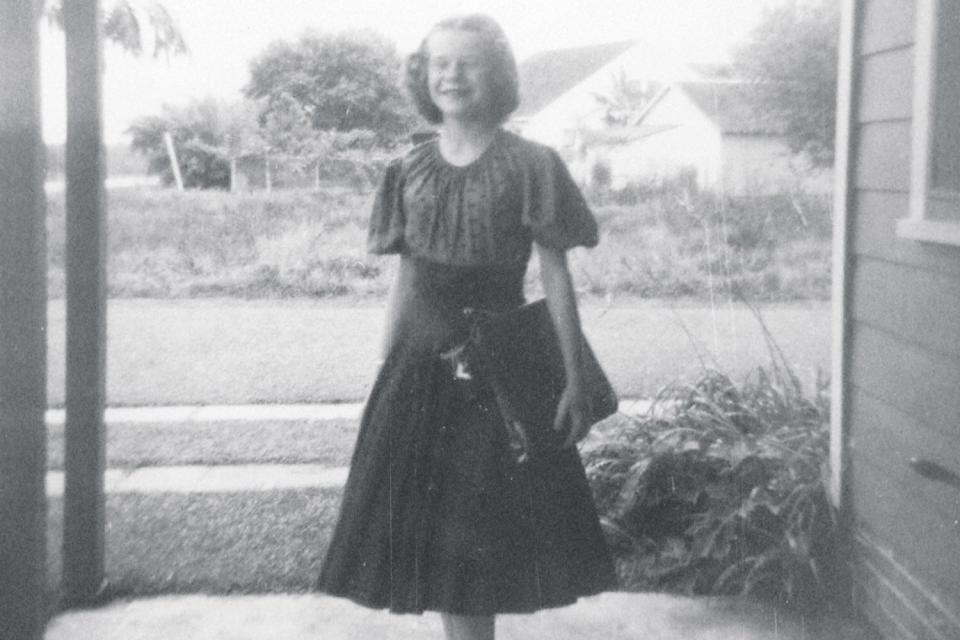

Copyright © Fantality Corp. Janis Joplin's first day of school in September 1955.

As a teen, Joplin shared her ideas through her writing. She won an award for English journalism in Junior High (reprinted in Days & Summers), and even wrote letters to the editors of TIME while still a student. But as she grew older, Joplin discovered a better way for her to get people to listen. It started with family singalongs to pass the time while doing chores. "Saturday was cleaning day," Laura remembers. "Everybody got their assignments. But first, the record went on the record player. It was cranked up full volume and everybody ran around doing their job and singing along. Music was always a part of our life."

Their mother, an operatic soprano who had harbored Broadway ambitions as a young woman, preferred show-tunes. She instilled in Joplin a lifelong love of the Gershwin classic "Summertime," which became a staple of her concert repertoire. Their father's tastes ran towards classical. "He would say, 'Sit down, sit down! Listen, just listen!'" remembers Laura. "He would play a particular phrase on a classical LP that he had. And he would look at you with this question: 'Can you feel it? Can you?'" Dorothy, meanwhile, was focused more on the mechanics, urging her children to sing from their diaphragms and enunciate. "Our parents had very different approaches to music," Laura continues, "but both of them felt music was important."

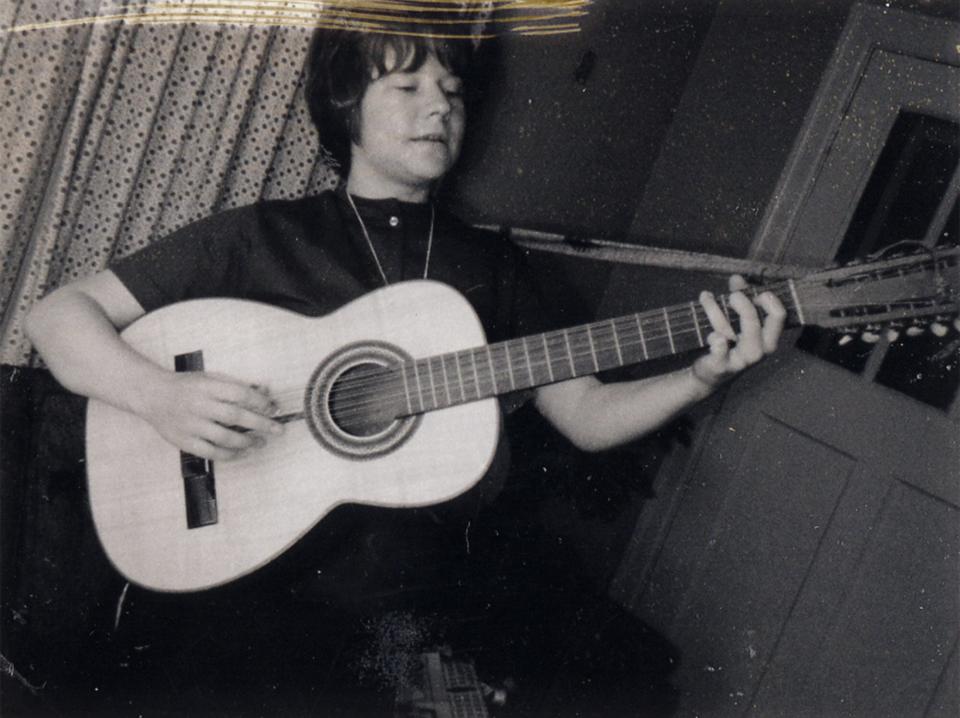

Copyright © Fantality Corp. The budding beatnik. Joplin plays guitar in the living room of her parents' Port Arthur home in 1964.

These twin influences, technique and emotion, formed the foundation of Joplin's developing vocal talent. "She sang church choir stuff when she was young," says Laura. "But what I remember most is when she picked up the guitar and started singing. That was partially influenced by her high school friends, because they listened to folk music and went out to concerts." Port Arthur was a musical hotbed, so Joplin and her gang of burgeoning beatnik cohorts didn't have to go far for a live music fix. "There was music everywhere at every nightclub," remembers Michael. "The Johnny Winter Brothers played every other Saturday at the roller-skating rink. ZZ Top played at my high school prom!"

When the opportunity presented itself, Joplin would climb onstage and join in. "She just kind of made it her own," says Laura. Later, Joplin embraced the sounds of blues pioneers like Leadbelly, Bessie Smith and Odetta. Port Arthur in the late '50s was still racially segregated and Whites were not welcome in venues that catered to Black patrons. So Joplin and her like-minded friends ventured across state lines to Louisiana, sneaking into blues and Cajun clubs while underage.

Her unorthodox interests and mile-wide individualist streak set Joplin apart from her peers, and the illicit late-night trips across the border — which drew the attention of local police on one occasion — solidified her reputation as a "bad girl" and an outcast. Joplin spent most of her adolescence ostracized by her community, and she resented it for the rest of her life. "We all wanted to get out of Port Arthur immediately. It was hell," says Michael. "Our parents even said, 'You need to leave as soon as you can.' It was just nasty. I got beat up because I wore bell-bottoms. It wasn't good…"

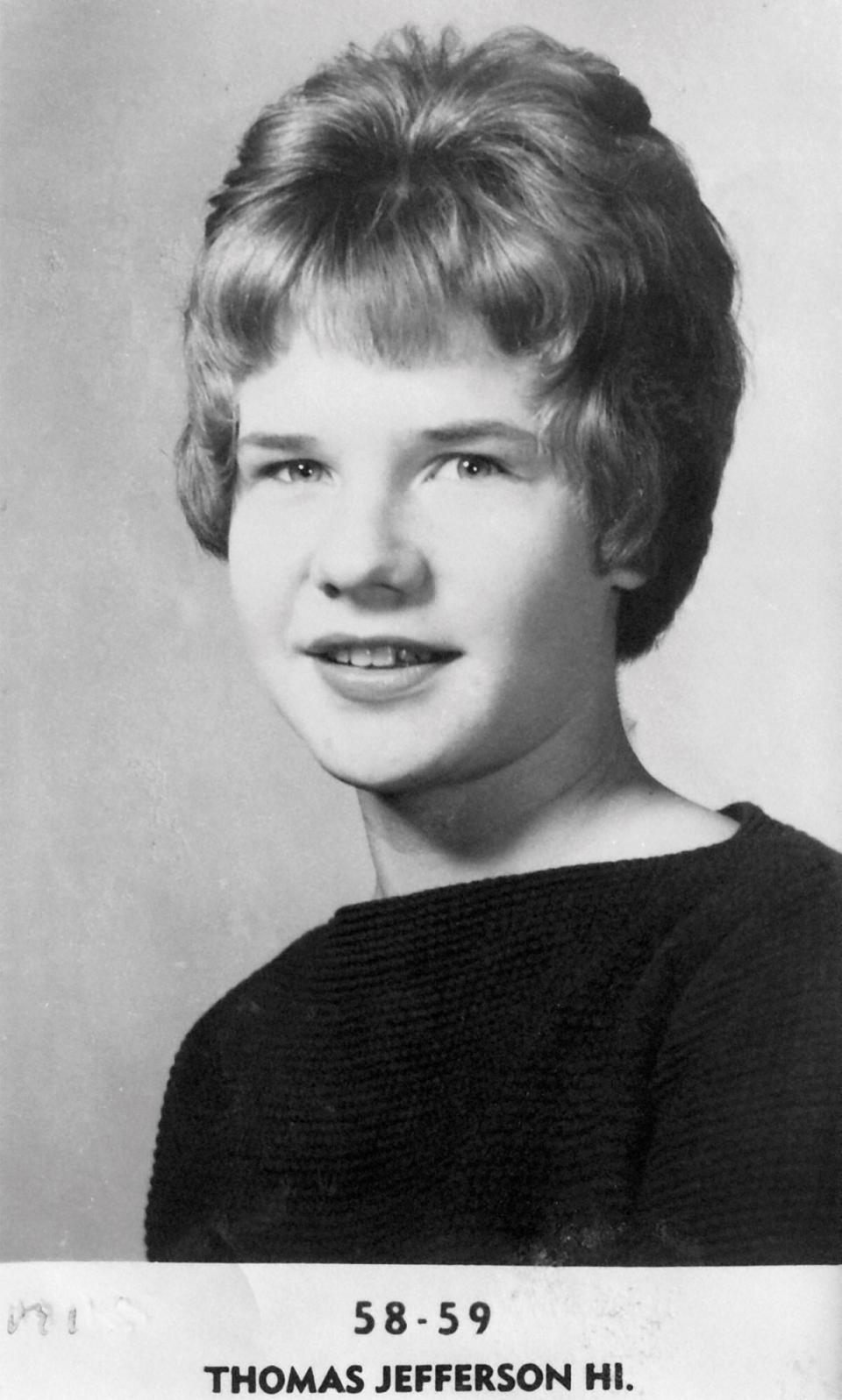

Copyright © Fantality Corp. Joplin as a junior at at Thomas Jefferson High School, circa 1958.

As a star, Joplin told Newsweek, "There wasn't anybody like me in Port Arthur." Michael agrees with the assessment. "Looking back on it, I think, 'Oh my God. In that town, our family was weird.' We were listening to classical music. Nobody else listened to classical music. Nobody listened to show tunes. That was too weird. But I didn't know we were weird. I relished whatever weirdness factor I could get. And I'm sure Janis did, too."

While attending a Texas college in 1962, Joplin was profiled by the campus newspaper under the revealing headline: She Dares to Be Different. Instead of following the crowd, she stood in front of one and earned acceptance through singing. "It gave her an identity," says Laura. "Music made her unique and appreciated. It gave her a feeling of importance and made her feel alive. It was something that she wanted to share that was important to her. Music was not casual. It was serious."

Music led Joplin to San Francisco in 1963, where she soon fell in with a destructive clique. She returned to Port Arthur two years later, broke and addicted to methamphetamine. Her emaciated frame weighed less than 90 pounds when she arrived at her parents' door, and she spent much of the next 18 months trying to, in her words, "straighten out." She re-enrolled in college, briefly became engaged, wore her hair in a modest beehive 'do, and generally followed the path expected of women in town. Her siblings were thrilled to have their big sister back home, but it quickly became clear that this wasn't the life she wanted.

When Joplin announced her intent to return to San Francisco in 1966 and throw herself headlong into her music, the response from her parents was mixed. "They were excited and also a bit scared," says Laura. "On the one hand they were worried because she'd been out there before and had problems. But they also knew she was doing what she needed to do. So they had their fingers crossed."

In the mid-'60s, San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood was a magnet for truth seekers, nonconformists and young runaways eager to tune in, turn on and drop out. Laura and Michael Joplin were probably the only kids who traveled to the hippie Shangri-La with their parents in tow. The family took a trip to the Bay in the summer of 1967, driving all the way from Texas to visit Joplin. "My father told me they just wanted to be sure she was okay," says Laura.

Any fears were allayed when they saw her perform at the Avalon Ballroom, one of San Francisco's premier psychedelic palaces. "As a young wannabe hippie, that was awesome," remembers Michael. "I was excited as all get out." Joplin had written letter after letter — many included in Days & Summers — breathlessly describing her new life and career, but that hadn't prepared her family for the experience of actually seeing her center stage with her new band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. "It was completely eye-opening," says Laura. "She told us stories in letters and telephone conversations, and we'd heard her [early] records. But sitting in a huge audience while she was up there controlling the emotional power of the room gave us an incredible awareness of what she had been living."

Copyright © Fantality Corp. Performing in 1969.

As far as Michael was concerned, his sister was in her element. "I remember thinking it wasn't strange to see her up there," he says. "Watching her, it just seemed perfect. It seemed like it fit her. Because it did." At last she belonged, and people were listening. "I remember turning around watching the audience more than watching Janis. We'd heard her sing a million times, so that wasn't an unexpected event. But looking around I thought, 'Oh my God, she's really reaching these people.' The way she touched the rest of the audience was very moving to me as her brother."

Fresh off her slot at the Monterey Pop Festival that June, Joplin quickly went global. As her notoriety increased, the entries in her scrapbook became more infrequent. "She just didn't have the time," says Michael. "It was like, 'Ah, whatever. I've been in every magazine now!' So that's an interesting personal touch, because it showed what fame was doing to her."

No matter how famous she became, she was still the same ol' Janis around her family. "Certainly there was a lot more drama when she was onstage," says Laura. "But when we went backstage to go visit with her after a show, she'd say, 'Hmmm, do you like these pants?' She was just always her."

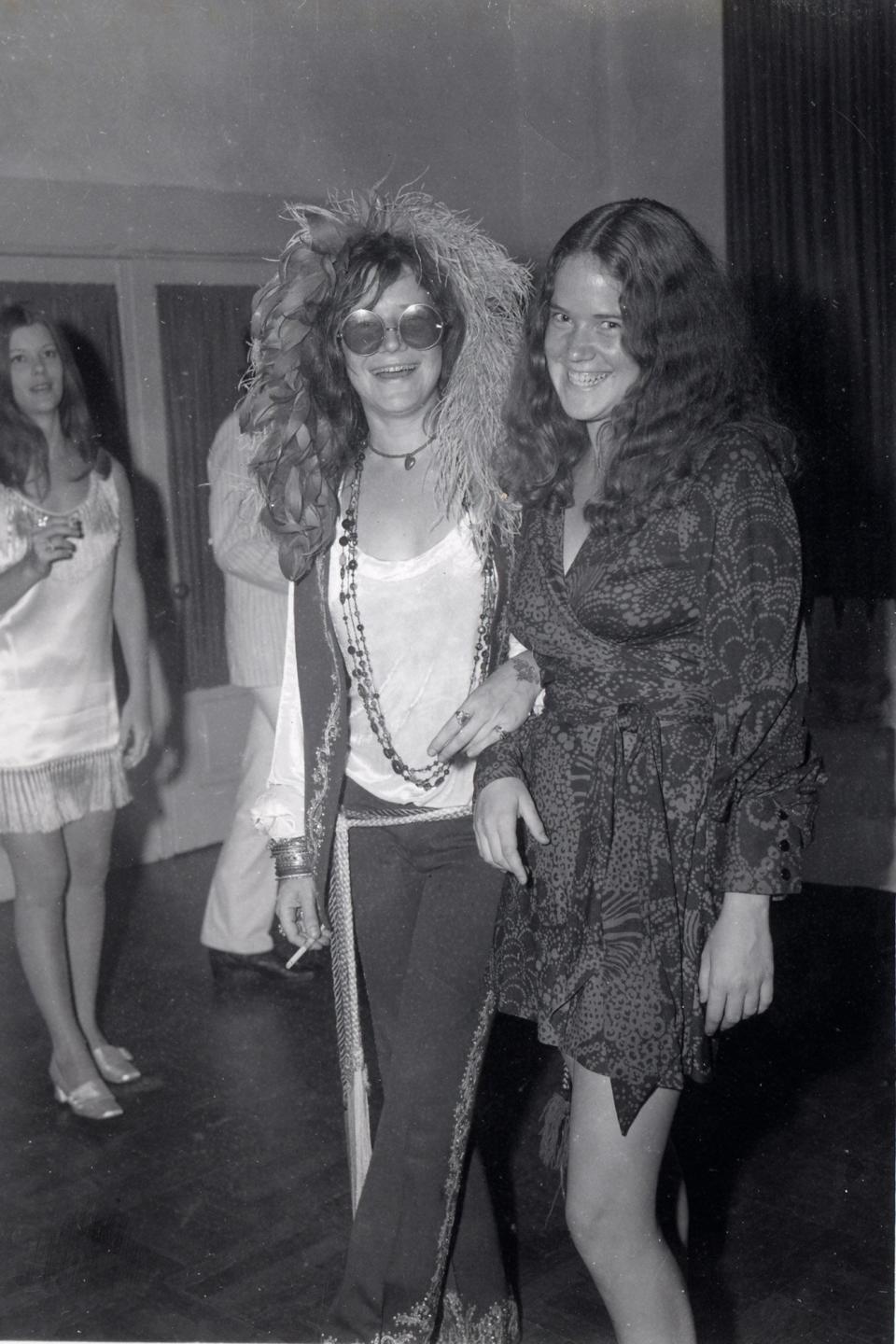

Copyright © Fantality Corp. With sister Laura at Joplin's 10-year high school reunion in August 1970.

Joplin continued to live up to her role as the elder sibling by recommending books to Laura, like Rosemary's Baby or J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy, and offering sisterly style tips. "She helped with my hair and told me how I should do my makeup," Laura says. "She was older, so I kept trying to get her to teach me how to do this or that. That was just the way it was — girl stuff." Joplin encouraged Michael's artistic side by sending him psychedelic San Francisco concert posters. When he painted a mural for a local youth club, she was effusive in her praise. "Honey, just congratulations + pride & all the love I have for your work," she wrote in a postcard included in Days & Summers.

Being the little brother of rock's reigning queen did have some advantages at Michael's high school, but fewer than one might think. "It was cool for a year. Before that, so many people were like, 'You f—ing hippie with your long hair…' It was a pretty redneck town. But then 'Piece of My Heart' was on the radio." The song became a Top 10 hit in the fall of 1968. "That's when I could get dates. So that was good!"

Yet there were times when sharing their sister with the world could be frustrating. Once, Joplin paid Laura a visit at her college dorm. Word of her arrival spread fast, transforming the campus into a minor mob scene. "I was in my room waiting for her," remembers Laura. "Then all of a sudden all these people were screaming, 'Janis Joplin is here!' I found Janis running up the stairs. We looked at each other and said, 'Let's go!' It was a shock. These were my friends and I thought they'd [be respectful] that my sister was visiting, but it wasn't that way at all."

If sharing Joplin's life was hard, sharing her death on Oct. 4, 1970 was even more difficult. This moment of private grief was unbearably public, echoing across televisions, radios and through hallways of Laura and Michael's schools. To Joplin's family, the songs that made her loved around the world became excruciating reminders of her absence. "It was really hard," admits Michael. "For years I wouldn't listen to her music because it hurt. I couldn't listen to her [interviews]. I didn't want to hear her talk because that was the person I knew."

Assembling Janis Joplin: Days & Summer was cathartic for the surviving Joplin siblings, who've each enjoyed rich and highly individual careers of their own. Laura earned a master's degree in psychology and a Ph.D. in education. In addition to working as an educational consultant, she wrote the superb 1992 memoir Love, Janis, which was later adapted into a stage musical. Michael is a master craftsman who works in glass out of his studio in Arizona.

Revisiting the scrapbook has allowed them both to reconnect with Joplin. Through Days & Summer, they hope fans will get to know their sister and not the superstar. "[The book] is like someone chatting with you about things and sharing stories," says Laura. "It's nice to see what a good time she was having. She had a short life, but at least she was having a really good time."

Copyright © Barry Feinstein Photography Inc. From the photo shoot for 'Pearl,' Joplin's final album, released posthumously in January 1971.

Michael concurs. "Janis loved to laugh. She was the center of the party. She always was. She laughed loud and she laughed hard. She was out to enjoy herself. I'm hearing her laughter right now. She had a great cackle." As evidence, he cites the track "Mercedes-Benz," recorded just days before her death, which concludes with a mischievous chuckle.

The song no longer causes him pain. Like the little skip offstage at Monterey Pop, it's a fleeting moment that reveals an unguarded moment of humanity. Days & Summer is filled with them.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance