How to Invest in Coffee Stocks

It's almost hard to believe that just a few decades ago, coffee shops weren't really a thing. In the United States, you got your coffee either from the instant variety at home or from your local mom-and-pop diner. But as the diner has declined, a legion of coffeehouses has stepped in to fill the gap.

Below, we'll discuss what's driving this growth, how big the opportunity is, how investable the three biggest names are, and how you should prepare your portfolio as a result.

Why is coffee so popular?

In the early 1980s, a young man from Brooklyn stepped onto a plane bound for Italy. The trip seemed perfectly ordinary back then, but time has shown it to be the first domino to fall in a complete reshaping of the relationship Americans have with coffee.

This man noticed that, for Italians, coffeehouses were more than just a location to get their caffeine fix. They were a "third place" -- outside of home and work -- for people and communities to gather. The coffee was surely important, but so was the social aspect of how it brought people together.

Image source: Getty Images.

That young man was Howard Schultz. When he returned to the United States, he set about turning a small Seattle coffee roaster named Starbucks (NASDAQ: SBUX) into the global behemoth it is today. He accomplished his success by focusing in equal parts on the coffee and beverages he provided and the ambiance of the stores in which people spent their time.

Fast-forward to today, and coffee consumption has grown by leaps and bounds. Since the 1990s alone, demand for coffee has increased by 50% worldwide.

Top coffee companies to invest in

Of the coffee companies you can invest in, here are the biggest names in the game, with approximate sales of coffee and other beverages for the most recent fiscal year.

Company | Key Brand(s) | Approximate Annual Coffee & Beverage Sales |

|---|---|---|

Starbucks | Starbucks | $18.3 billion |

Nestle (NASDAQOTH: NSRGY) | Nescafe, Nespresso | $9.3 billion |

Restaurant Brands (NYSE: QSR) | Tim Horton's | $4.9 billion* |

Dunkin' Brands (NASDAQ: DNKN) | Dunkin' | $4.9 billion |

Keurig Dr Pepper (NYSE: KDP) | K-Cups, Green Mountain | $3.2 billion |

J.M. Smucker (NYSE: SJM) | Folgers, 1850 | $2.5 billion |

Data source: SEC filings. Numbers approximate annual sales based on most recent available data from 2017 or 2018.

*Because Restaurant Brands does not break out coffee and beverage sales for Tim Horton's, a proxy of 74% of sales was used, as this is the breakdown at rival Starbucks.

How big is the coffee market?

The global market for coffee in all its forms -- instant, prepared-in-store, K-Cups, you name it -- has gone through tremendous growth over the past 20 years.

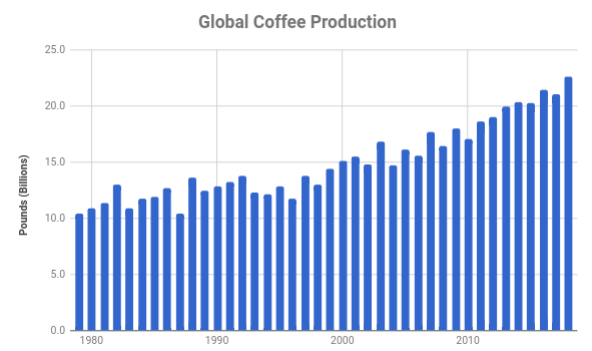

Luckily for those of us who rely on our daily fix of caffeine, production has kept pace. In 1978, the world's coffee growers -- almost uniformly small family farms, because of the inability of large corporations to mechanize the coffee-picking process in mountainous regions -- produced 79 million bags of coffee. At about 132 pounds per bag, that's roughly 10.4 billion pounds of coffee.

And while that might sound like a lot, it would be nowhere near enough to meet demand today. Thanks in large part to production surges in Brazil and Vietnam, this is what the production has looked like since.

Data source: SEC filings.

Even more impressive is the fact that the amount of land devoted to coffee growing has shrunk by about 30% since the late 1960s to 10 million hectares. At the same time, however, the amount of coffee the average hectare produces has doubled -- to 2,600 pounds of coffee as of the period between 2005 to 2014, the most recent available figures. We can thank improved efficiencies in both agricultural practices and chemical use for that increased production.

To give a rough estimate for the total global coffee market, let's combine the production and approximate price per pound of the two major types of coffee -- arabica and robusta -- in 2018.

Type | Production | Approx. $ per Pound | Production Value |

|---|---|---|---|

Arabica | 13.5 billion pounds | $1.29 | $17.4 billion |

Robusta | 9.2 billion pounds | $0.78 | $7.2 billion |

Total | 22.7 billion pounds | $1.08 | $24.6 billion |

Data source: USDA, YCharts.

While $24.6 billion might sound like a big number, it's actually just the tip of the iceberg. That's just how much money goes toward the farmers who produce the coffee. When that coffee is shipped to companies throughout the world, the beans are in their green (unroasted) state.

Because some weight is lost in the roasting process, this is equivalent to about 18.8 billion pounds of roasted coffee. That roasted coffee gets sold as is, used to make packaged goods, added to things like ice cream, or brewed and sold as a hot (or cold) beverage.

That's a wide range of uses, and it's impossible to break down how all of that coffee gets used. For hypothetical purposes, let's say the average pound of roasted coffee -- the lowest gross-margin use -- sold for $10. That would make the low end of the annual global coffee market worth almost $190 billion.

The high end would come from assuming that all of the coffee gets brewed and sold as a ready-to-drink beverage. Let's say the average pound of coffee produces 20 16-ounce cups of coffee -- each valued at $2.50 apiece. That means a pound of coffee is worth $50 in gross profit for a coffee shop. This is an incredibly high-margin endeavor, and it should help you understand why companies like Starbucks can be so profitable. It pegs the high end of the annual global coffee market near $940 billion.

The reality is somewhere between these two huge numbers, but suffice it to say this: The global coffee market is enormous, probably well over $350 billion per year.

Why is the coffee market growing?

Three areas have driven the lion's share of growth in global coffee consumption over the past 20 years: the European Union, the United States, and Brazil. Combined, these three consume 50% more coffee per year than they did in 1998.

This growth is owed not to a single factor but to a combination of forces. Schultz and Starbucks turned Americans into a nation of coffee drinkers. While soda got a bad rap for its sugar content, coffee became the vehicle of choice to get our caffeine fix. And while Schultz originally planned on making Starbucks a "third place" for people to gather, the ubiquity of drive-thru options to help us meet the demands of our ever-busier lives probably hasn't hurt either.

Younger generations have also embraced coffee culture en masse. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of 18- to 24-year-olds consuming coffee jumped from 34% to 48%, according to Mordor Intelligence. Over the same time frame, daily consumption by 25- to 39-year-olds jumped from 51% to 60%.

Concurrent with that has been the rise of the global middle class. Brazil is a perfect case in point: Its coffee consumption has grown the most -- over 75% -- in the past 20 years. But it's not alone. In 1965, roughly 27% of the world's coffee was consumed in either emerging or coffee-producing economies. By 2015, that ratio had jumped all the way to 46% of the world's coffee consumption. Coffee is becoming a staple of middle-class life around the world.

Finally, there are the economics of coffee. As I stated in the above section, selling brewed coffee can be incredibly profitable. Coffee shops can buy a pound of coffee for as little as $1.50. They can roast it, brew it, and extract as much as $50 in revenue from it. Of course, there is a bevy of other expenses to consider -- like rent, employees, energy consumption, and the like. But margins like that are hard to come by.

Risks in the coffee market

Just because coffee is both wildly popular and incredibly profitable doesn't necessarily make it a great investment. There are two aspects to consider: the cost of coffee beans themselves and the onslaught of competition when it comes to coffee shops. Let's tackle them in order.

Environmental threats drive coffee prices higher

Nothing is more fundamental to the business than the supply of coffee beans. Advances in both agricultural practices and chemical usage have made lands far more productive today than they were 60 years ago.

But that's come at a price -- one I'm very familiar with, since I live with my family for part of every year on a small family coffee farm in Costa Rica. Many coffee farms of the 1960s produced far more than just coffee -- they offered up fruits, vegetables, and legumes for their communities as well.

Part of the increased production has simply come from adopting full-scale monoculture. The same way that the cornfields of my native Wisconsin rarely have any other forms of life living in them, the same is true for mountainous coffee regions -- they are now bare hills with coffee planted, with sparsely spaced cover trees.

That lack of diversity has consequences. Starting in 2009, for instance, a rust fungus started showing up on the leaves of coffee plants in Latin America, causing farmers to lose the beans before they were picked. Coffee production in Colombia, to name just one affected area, fell a whopping 40% between 2008 and 2012.

The farm we live on -- which started practicing biodiverse farming in the 1990s because chemicals made the owners sick -- was far less affected. This was due mainly to diversity: The fungus had more plants to attack, and its natural predator -- a white fungus -- already lived on the farm.

Since then, farmers have discovered rust-resistant coffee plants to boost production. Even then, however, farmers in Honduras started reporting in April 2018 that those "rust-resistant" plants aren't as resistant as once hoped. Only time will tell what the next "rust fungus" is and where in the world it might strike.

The use of chemicals, combined with the side effects of climate change, looms on the horizon. The International Coffee Organization predicts that by 2050, huge swaths of Brazil, Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia will no longer be suitable for arabic coffee production. That means coffee producers need to make significant investments now to prepare for this change.

Many of these farmers, however, are dealing with historically low prices for coffee. That's great for coffee companies right now -- but it's a double-edged sword. Because many coffee-producing countries don't have the resources to make these investments, they could suffer mightily in the not-so-distant future. That could lead to significantly lower yields, which in turn could mean much higher prices for coffee.

And when those higher prices hit, those coffeehouses are going to either pass those costs along to customers or keep prices the same and deal with lower margins. And when those lower margins hit, expect coffee company stocks to respond in kind.

Competitive risks

Remember, most of coffee's growth in the United States is coming from millennials. A whopping 60% of older millennials and 48% of the younger cohort drink coffee on a daily basis. That's a ton of coffee drinkers.

According to research by former hedge fund manager Mike Alkin, millennials predominantly want three things from the goods that they buy:

They want them to be, when possible, organic.

They want them to be local. In the case of coffee, that would mean local roasters.

They want them to be from a small company rather than larger behemoths.

While the coffee companies I'll describe below would have little problem providing organic coffee for their customers, they can't fit into the latter two categories. Part of the nature of being a publicly traded company is that your shareholders demand that you at least try to grow your presence. That means there's little chance of being considered "local" or "small."

But smaller, private, independent roasters don't have that problem, and they're cropping up all over the place. In my hometown of Milwaukee, for instance, Starbucks isn't even the first or second option when people get coffee. We have a wide array of roasters that are packed on a regular basis. And Milwaukee isn't alone: According to Statista, the number of specialty coffee shops in America grew 47% between 2005 and 2015 to 31,400.

If we really want to get down to brass tacks, coffee businesses have no moats around them -- no sustainable competitive advantage over rivals. Moats come in four primary forms:

Network effects: Each additional customer adds value to other customers. This doesn't apply with coffee, since my coffee doesn't taste any better just because you bought your own cup.

Low-cost production: One or more companies can offer up a product of equal value for less than the competition. This might be true for some companies when they sufficiently scale, but as we discussed in the case of millennials, low costs aren't always the biggest driving force.

High switching costs: It would be prohibitively expensive for customers to switch providers. Admittedly, some companies use rewards points and loyalty cards effectively enough for this to be considered a moat. But it's still a relatively weak one.

Intangible assets: patents, government protection, and brand value. Typically, brand value is the main driver of coffee companies' moats. Indeed, it's what's been driving Starbucks' results for over two decades. But that, too, is being turned on its head by millennial preferences.

Starbucks dominated the industry for so long for two reasons: Schultz saw what others didn't in creating these third spaces with a coffee focus, and for previous generations, big brand names mattered.

On the former, the cat is out of the bag: The business world is well aware of the favorable economics of the coffee business. On the latter -- as I've harped on for much of this section -- brand power simply isn't what it used to be.

To be clear, I do not think these companies are doomed. They will continue to do business and provide coffee for legions of people across the globe. But we need to separate the companies from their respective stocks. Using Starbucks, Dunkin' Brands, and Keurig Dr Pepper as examples, here's why I don't think you should be investing in any coffee stocks.

Starbucks

As you might have already guessed, Starbucks is by far the most important coffee-related company in the world. It is valued at more than $85 billion today and has more than $25 billion in sales over the past 12 months alone. It also has an enormous presence globally.

Number of Locations as of 2018 | Countries |

|---|---|

Over 14,600 | United States |

Over 3,500 | China |

Over 1,000 | Canada Japan Korea |

Over 500 | United Kingdom Mexico |

Over 350 | Taiwan Turkey Philippines Indonesia Thailand |

Data source: SEC filings.

But recently, the trends have not been in Starbucks' favor. Coming out of the Great Recession, many smaller coffee shops folded. Though Starbucks' stock fell as the market did, the recession actually helped -- it cleared out swaths of smaller, more local competition. As the economy recovered, the company dominated.

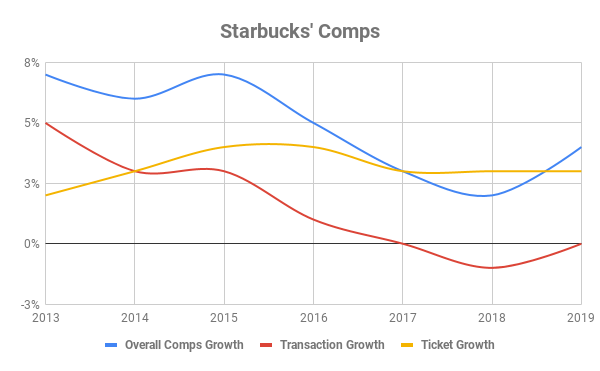

One of the most important ways to measure a restaurant stock like Starbucks is via comparable-store sales (comps). This takes all the stores that were open one year ago and compares them to sales in the current year of the same cohort. That last part is important, because it backs out the effect that opening up new stores has and drills down to the core strength of the company.

Here's how Starbucks has fared, domestically and abroad, over the past six-plus years.

Data source: SEC filings. Note that 2019 is for first fiscal quarter of the year.

While a recent bump up to 4% comps (blue line) is very encouraging, it's important to note where that growth is coming from. It is entirely from increases in what Starbucks is charging its customers (yellow line). Traffic into stores -- or the number of people buying coffee at existing Starbucks stores -- hasn't increased in two-plus years!

Those who believe in the company will point to enormous growth potential in China. They're not wrong. But in 2018, traffic in the China/Asia Pacific region shrank 1%. That's not the type of growth many were expecting.

And almost overnight, competition has begun showing up. Luckin Coffee didn't even have a Chinese location in 2017. Two years later, there are more than 600 -- with plans to continue that brisk growth.

Like I mentioned, I don't believe this is a death knell for Starbucks. Even after you back out a huge one-time payment it got from Nestle for the Global Coffee Alliance, the company has churned out plenty of free cash flow. But given the dual headwinds of increased competition and the very real possibility for increased coffee input prices in the not-so-distant future, I don't think Starbucks is a very solid investment.

Dunkin' Brands

Next up is America's long-standing No. 2 source for prepared coffee: Dunkin' Donuts. Whereas Starbucks owns and operates about 60% of its locations and franchises the rest, Dunkin franchises all of its locations. Baskin-Robbins ice cream shops also fall under the Dunkin' Brands umbrella -- so this isn't a pure play on coffee, either.

The advantage of the franchise-only model is that overhead costs are very low. Franchisees pay Dunkin' to obtain a location, plus royalties based on sales, advertising fees, and, in some cases, rent for land that the company owns. While Dunkin's overall revenues are much lower, margins are much higher.

Because you can't just invest in the coffee side of this business, we need to take a look at the broader picture, which includes international operations and Baskin-Robbins. Here's how the segments broke down in terms of locations and sales in 2018.

Type | Total Locations | 2018 Annual Revenue |

|---|---|---|

Dunkin' U.S. | 9,419 | $607 million |

Dunkin' International | 3,452 | $22 million |

Baskin-Robbins U.S. | 2,550 | $47 million |

Baskin-Robbins International | 5,491 | $115 million |

Data source: SEC filings.

It's important to note that those sales figures don't mean that all of Dunkin's stores in the U.S. brought in $607 million in sales. That would be ridiculously low, equating to roughly $176 in sales per location per day.

The truth is that Dunkin's U.S. operations brought in $8.8 billion in systemwide sales, with coffee and beverages accounting for 58% of those sales.

The figures above, then, represent payments to Dunkin' from franchisees. The agreements between Dunkin' and franchisees generally last 20 years -- which means that they are largely locked in. That being said, royalty payments depend largely on how each location is doing. Each Dunkin' U.S. location, for instance, pays 5.9% of gross sales back to Dunkin' in the form of royalty fees.

The important thing to note is that you can see how important Dunkin's U.S. operations are to the entire business, followed by Baskin-Robbins' international operations.

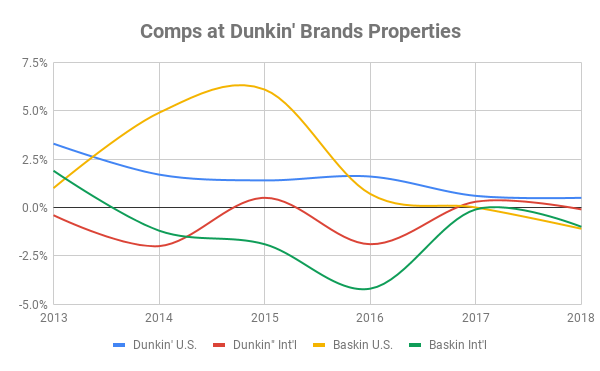

While Dunkin' has been benefiting from the operating leverage that this franchise-only model has offered, the long-term trends are not moving in the company's favor. Peeking at comps over a similar time period as Starbucks, we see a familiar trend.

Data source: SEC filings.

As with Starbucks, I hardly think the company itself is in serious trouble. Millions of people go to Dunkin' -- and Baskin-Robbins -- every day. But as a long-term investor, I'm concerned that the company's comps are so low, and I see serious input (coffee prices) and competitive pressures on the horizon.

Keurig Dr Pepper

Finally, we have Keurig Dr Pepper. The coffee part of this company used to be Green Mountain Coffee Roasters -- makers of the K-Cups for coffee machines that became so commonplace 10 years ago. In fact, in 2015, Green Mountain provided more coffee for Americans than Starbucks -- though at a much lower sales level.

But then the patents on the K-Cups and their machines ran out, and competition quickly flooded the market. Green Mountain went private in late 2015 and reemerged last year in a Keurig-Dr Pepper merger.

We don't have a ton of visibility into how the coffee side of the business -- Keurig -- has performed over the past few years, as the company has only been publicly reporting for a few months. As it is, the combined company includes K-Cups and coffee machines on the Keurig side and a stable of beverages and soda products that includes Dr Pepper, A&W, Sprite, Canada Dry, Snapple, and Yoo-hoo, among others.

But in the combined entity, coffee is definitely the most important part, bringing in a majority of sales and operating profit.

Again, the trends in the coffee business aren't encouraging:

Losing patent protection has eroded K-Cups' sales, pricing power, and competitive advantage over rivals. Consumers are shopping for the cheapest product, with little consideration for brand loyalty.

Coffee machines -- which include a number of new releases -- are adding hope but not much more. Appliance sales were essentially flat in 2018.

As with the other companies I've talked about, I don't think Keurig Dr Pepper will disappear. But given that the business has demonstrated little in the way of competitive moats, I don't think it's a promising long-term investment.

Who should (or shouldn't) invest in these stocks?

If it seems like I'm not optimistic about the future of coffee stocks, you're right. While I think coffee will remain popular for years to come, I think the main benefits will accrue toward those who start up small and local coffee shops.

And again, all of these coffee companies -- Starbucks, Dunkin', Keurig Dr Pepper, and their brethren -- will continue to be just fine. But we have to look at what's happening versus the optimism priced into their stocks. To me, there's too much optimism in those stocks as of this writing.

Keep a close eye on these companies' price-to-earnings (P/E) and price-to-free-cash-flow (P/FCF) ratios, especially in relation to those of the broader market. Broader market P/FCF ratios are harder to come by, but over the long run, P/E and P/FCF mirror each other. In general, I like P/FCF better because it measures the amount of money a company gets to keep in its pocket after all is said and done, whereas P/E has more accounting gimmicks that can mask what's really going on.

When coffee companies' P/Es exceed the S&P 500's P/E, both current and long term, it suggests that investors think coffee stocks will do better than the overall market in the future. Given the challenges I've outlined above, that seems unlikely to me.

Should these stocks' prices or ratios fall significantly, I might reevaluate my opinion. For now, I think -- as far as coffee is concerned -- your best investment is to find your favorite coffee, buy a grinder, and make your own coffee at home.

More From The Motley Fool

Brian Stoffel has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Starbucks. The Motley Fool recommends Dunkin' Brands Group and Nestle. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance