They Hunt Cartel Killers

YOU NEVER FORGET your first murderer, they say — though few cops recall the killers they caught as charitably as Vargas does. At the wheel of his seven-seat Escalade — a car that drives like an opium dream and is fancied equally by narco bosses and the retired federal agents who chased them — Vargas speaks of the Camacho-Higuera brothers like promising kids who made a rash mistake. That isn’t, strictly speaking, the official view. The brothers were the nephews of Ismael (El Mayel) Higuera-Guerrero, the chief of operations for the Arellano-Félix Organization. For most of the 1990s till the mid-to-late aughts, the AFO ran Tijuana, Mexico, like a Chicago slaughterhouse. It killed and beheaded street cops, cooked the flesh of its rivals on flaming tires, and delivered bodies by the hundreds to a man it called El Pete. Pete then dissolved the corpses into chunks of stew and poured the liquid remains down a drain. The AFO didn’t invent those horrors, but it certainly seemed to take more relish than most in its merry disembowelment of the dead.

Vargas, who retired last summer as a special agent with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, doesn’t despise the cartels or demonize the killers who did their grunt work. Those “mopes,” as he calls them — the hit men, kidnappers, bent cops, and smugglers — were pawns in an industry with no way out, and whose wages were generally paid in blood. “Not to excuse them, but these people are human,” he says. “They have wives, they have kids; someone loves them.” (Vargas — at the insistence of his wife and children — asked that I change his name. So, too, did the other cops on his squad who spoke to me for this story, out of concerns for their safety and that of their loved ones.)

More from Rolling Stone

Mexico to Level Massive Fine Against Ticketmaster After Bad Bunny Ticket Disaster

Ivan Cornejo Goes Through Every Stage of Heartbreak on 'Ya Te Perdi'

His solicitude aside, Vargas hunted those men to the exclusion of all else. While his friends and colleagues at the alphabet shops (the FBI, DEA, ATF, et al.) obsessed over the top-of-org-chart types — the kingpins, lieutenants, and logistics wizards of the cartels — Vargas went after their murderous gunsels on the streets of San Diego. He and his extraordinary team of trackers — a crew of six detectives in the Criminal Aliens Squad (or CRIM, for short) — did something undreamed of in the nearly 100-year history of the CBP. Rather than chase migrants, they chased menaces instead, and caught 300 felons in five years. In the process, Vargas flipped the role of Border Patrol agents: He turned them into bloodhounds for other feds. “Because we were quote-unquote ‘Immigration,’ we could sack up bad guys no one else could touch,” he says. “Even if they had a legal right to be here, we had tools to take them off the chessboard.”

“They could reach out and touch anyone on this side. Even bad guys who weren’t on our radar,” says Steve Duncan, a retired special agent for the California Department of Justice. Duncan was assigned to the Group One Task Force, a legendary squad of state and federal agents who broke the AFO after 20 years.

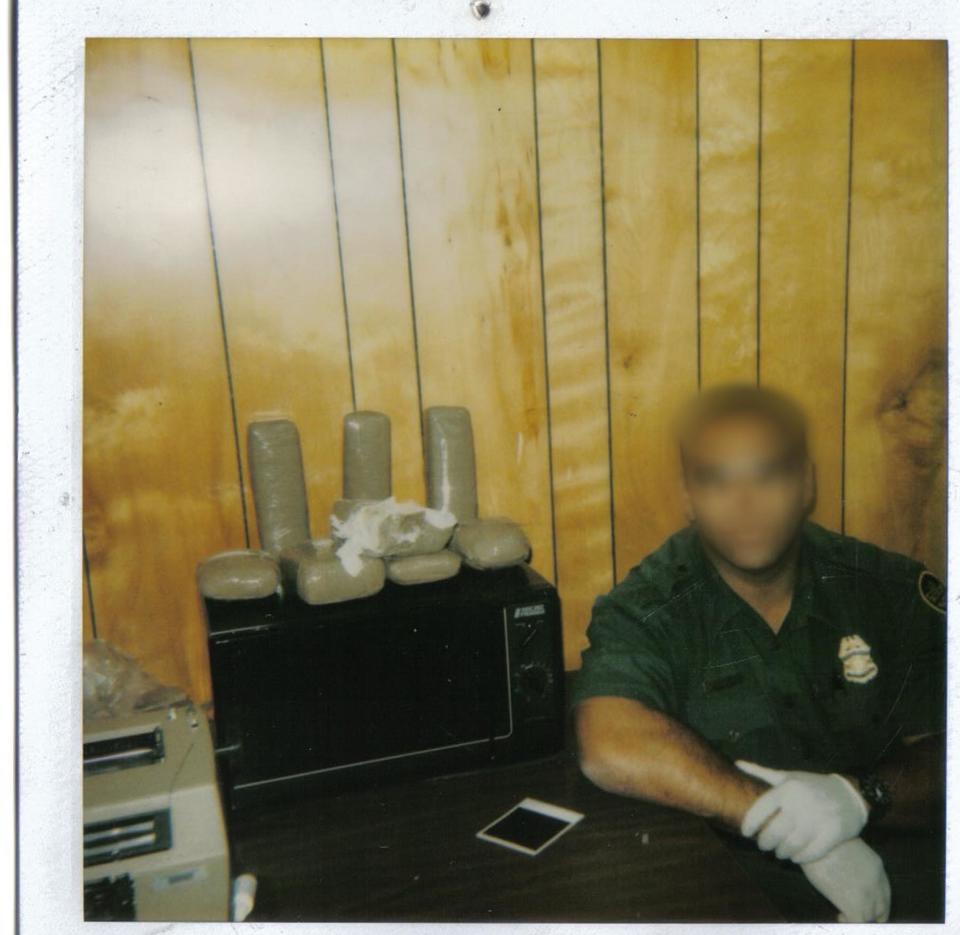

That list includes Carlos and Ismael Camacho-Higuera, the hothead brothers whom Vargas’ squad collared in the spring of 2006. “They were narco-juniors working their way up the line: moving loads across for AFO,” Vargas says. In the fall of 2003, one of their U.S. clients flew to Baja California to do a drug deal. While sitting and drinking beer at the brothers’ house, the buyer remarked on the shrine they’d erected to their imprisoned Uncle Mayel, the cartel capo. (Mayel had been busted by the Mexican army in 2000 and sentenced to serve decades in prison.) “If Mayel’s such a badass, what’s he doing in a cell?” snarked the visitor, misreading the room by a mile of blow. Some days later, he was found in the mountains; 18 slugs were fished out of him. “There are certain jokes you don’t make,” says Vargas. “To those boys, their Uncle Mayel was a saint.”

I haven’t met a fed as empathetic as Vargas in 20 years of covering the War on Drugs. Of the 14-year-old sicario who beheaded another kid, then casually confessed to the cops, Vargas winces, saying, “I talked to his mother. He had a brutal childhood; he was raised by the streets from age seven.” Of the man they called El Yeyo, a former cop in Tijuana who took part in AFO crimes so vile they don’t bear summaries, “they told him, ‘Take our money or take a bullet in the head.’” There’s no animus or moral insult in his tone — just a feel for the context of such acts. It was his wide-lens view of the War on Drugs that made Vargas a brilliant cop: the ability to see patterns, not pointless depravity, in the crooks coming over from Tijuana. From those patterns — and a set of underutilized laws — Vargas built a web to catch cartel killers before they killed again, in the U.S.

Cartels don’t send many killers anymore; instead, they just send poison. In 2021, 107,000 Americans died of overdoses, two-thirds of which were caused by synthetics, according to a high-ranking official with the DEA, who, for political reasons, asked that I not name him. “Six of every 10 pills we seize off the street carry a potentially lethal dose of fentanyl,” he adds. “Those pills are mass-produced by the cartels — and their chemists don’t care about dose strength. For every 100,000 they kill in this country, they know there are 3 million users right behind them.”

Still, we’ve never before had an account of the days when sicarios roamed our streets, hunting civilians and fellow soldiers on U.S. soil. Vargas, a hand-to-hand combatant of that war, is taking me on a tour of his biggest busts in San Diego. Over there, off H Street, is the mini mart where Vargas’ CRIM Squad ambushed Furcio and a woman. Furcio (cartel slang for “big ears”; real name: Andrés Ramos Castillo) ran a crew of hit men who were hunting for Los Palillos, according to Vargas. The Palillos, a maniacal squad of sicarios who had turned against the AFO, were gunning for yet a third crew of killers in San Diego. Vargas shows me the place on Brandywine Street where the Palillos ditched a van stacked with corpses. When the stench summoned the cops, they found the van full of cash; there were toothpicks strewn across the victims’ corpses. “They left the cash to show that this was vengeance, not money,” says Vargas. “Toothpicks were their calling card.” (“Palillo,” of course, is “toothpick” in Spanish.)

The madness of such doings in a setting this splendid is hard to reconcile. East Chula Vista is a magic place, the topographical love child of the American Southwest and the Pacific Ocean. It climbs the khaki foothills of the Otay Mountains as it takes the eastbound pass out of San Diego. Pines and jacarandas shade the rutless roads that jog by ivy walls of gated enclaves. A salt breeze scrubs the air a shade of topaz-blue, and the light that hits the roofs of these seven-figure villas gives the low spark of high-heeled money. With one note of grace that bears mentioning here: Nearly everyone is brown. Here, the American dream goes big — a class of Mexican strivers who came, saw, and conquered for the right to be soccer moms.

We loop back down to the suburbs of National City, where the CRIM Squad cornered the Camacho-Higuera brothers. On K Street stands the complex where the brothers were hiding. The buildings in National City are old and stooped. Backed by a tactical unit, Vargas’ squad approached the door. One of the brothers answered when they knocked politely; as they cuffed him, the other brother pulled up. He parked behind the building and met a second car. Feds with long guns swarmed both cars. They arrested four men, including the brother. One of the other collars was a kid they called Pelon, a.k.a. Ponciano Frausto-Lopez. His name rang a bell; he was connected to Los Palillos, the gang that was shooting up San Diego. Pelon, however, wasn’t holding drugs or guns, so they brought him to the station, then cut him loose.

I brought in CRIM Squad ’cause those guys were regulators. The best bunch of hunters you ever saw.

Within hours, Vargas’ CRIM Squad was handing off the brothers to their Mexican counterparts at the border. There used to be a gate there called Whiskey Two: a door in the wall that only the feds could unlock. The brothers froze; one of them shrieked as men in balaclavas dragged them off. “The police there play by different rules,” says Vargas. “They do what you’d call ‘enhanced interrogations,’” which may or may not feature a shaken can of Coke sprayed up the nostrils of detainees. Vargas wasn’t told what crimes the brothers copped to, but he does know a couple of salient facts. First: The brothers got decades in prison. Second: They were the lucky ones. That kid they called Pelon? He was last seen in a bar, then taken, tortured, and dismembered. His killer, an AFO lieutenant named Victor Escobar-Luna, had a compelling motive. Pelon’s crew had kidnapped Escobar-Luna’s brother, then killed him despite being paid a ransom. Rather than make Pelon “stew,” however, Escobar-Luna stored his remains in a freezer. “Whenever [Escobar-Luna] moped about his brother,” says Duncan, “he’d go and open the freezer. I guess that’s what [sicarios] do for therapy.”

WITH APOLOGIES TO Narcos and the countless films and series sipping from the goblet of cartel content, there’s little or no profit rehashing the narco feuds that have exacted a hellish toll, making life all but lawless for our southern neighbors. Since the big-bang moment of mob butchery in 1993 — the unintended murder of Archbishop Posadas by a crew of hit men aiming for El Chapo — narco warfare has claimed or poisoned millions of Mexican lives. Kingpins like Chapo are now imprisoned or dead, their empires a jumble of chockablock shards that their successors kill to reclaim. Journalists, police chiefs, women, and tourists: Everyone’s in the crosshairs these days. Of the 10 deadliest cities, per capita, in the world, Mexico scores five or six in a given year.

It’s an article of faith among the men and women who patrol our southwest flank: What happens in Mexico doesn’t stay there. In cities that host a major port of entry — Laredo and El Paso, Texas, and Nogales, Arizona, for starters — there’s a complex balance between commerce and crime for cops to confront. Nowhere is that riddle harder to solve than in greater San Diego. By all objective measures, it’s a model metropolis. Ranked among America’s safest, cleanest towns, it’s praised for fiscal health by good-governance groups, and exalted for both its beaches and civic stability.

But it’s also home to the busiest border crossing of any land-based port outside of China. Seventy thousand vehicles travel north each day, as do 20,000 workers walking in from Tijuana. Once across the border, it’s a straight shot up I-5 to the distribution hub of Los Angeles. Meanwhile, under the border, dozens of narco tunnels link warehouse districts on either side of the fence. Through those durable holes pour billions of dollars a year in fentanyl, methamphetamine, and the tainted pharmaceuticals that kill U.S. teens on campuses every day.

All of which explains why the plaza of Tijuana is paved in blood and treasure. It is where Chapo commissioned his first tunnels, baiting the AFO into a gunfight. It is where the AFO, a clan of seven brothers, killed anyone else who trucked product through their streets without kicking up to the family. And it is where, after the brothers’ arrests or violent deaths — one of them, Ramon, was shot by a cop; a second, Francisco, was shot by a clown at his 64th-birthday party — war broke out between a series of butchers who broke the golden rule: Don’t kill civilians, especially rich ones.

The worst of said butchers was the monster called El Teo. A lackey who killed his way up the ladder as an enforcer for the AFO, he rose to lieutenant, then broke with the AFO when the last brother fell in 2008. He announced his intention to seize the plaza with a shootout that left 13 people dead. From that day forward, the streets ran dark with blood. Each morning dawned on fresh atrocities: corpses hung from the balustrades of bridges; cops beheaded and their bodies arrayed to spell out Teo’s nickname: 3L. Teo, untouchable, paraded through town in his convoy of SUVs, while his crews snatched innocents off the streets and tortured them to squeeze money from their families. “He killed doctors and the middle class, even when they paid the ransom,” says a Mexican official we’ll call Seven. Seven, a former police chief of Tijuana, worked closely with Vargas for most of a decade. They would often meet discreetly at a 7-Eleven in San Ysidro — he liked the American Slurpees better than Tijuana’s. “Teo dumped them in the street with their fingers off, and bruises all over their body,” says Seven.

It was into this crucible that Vargas stepped when he took over the CRIM Squad in 2007. For the next five years, he and his men slept in their cars, rarely getting home to hug their wives and kids. Instead, they put in 90-hour weeks, flushing out narcos who had sneaked across the border to kill or kidnap targets in San Diego. No one told them how those captures linked to El Teo or his enemy, Fernandito, of the AFO. They were miners with their heads down, sifting through the dirt. It would be years before they learned the value of what they’d found: the bodies that brought a SWAT team to Teo’s door.

IN 1998, Vargas joined the Border Patrol, when it was strictly a reactive force. “Line watch” was the mission of most of its agents: waiting in their Broncos for “illegals” to cross, then chasing them down and cuffing them for deportation. It was lonely, joyless labor, as Vargas learned. One night, he was sitting in his SUV in the pitch-black desert of Arizona. He and a second agent were parked mirror to mirror, when they heard an H-1 Hummer belching toward them. “We flipped on our wig-wags [dome lights] to tell them, ‘Don’t even try us tonight.’” The next thing Vargas heard was a fusillade of bullets blasting out the windows of his partner’s truck. Hopelessly overmatched — there was a machine gun mounted on the turret of the Hummer — the agents fled in separate directions and called for backup, which never came. “Back at the office, I’m filing my assault-on-a-federal-officer [report], and the supe’s like, ‘Whatever. That shit happens all the time.’”

That shit, Vargas learned in his four years watching the line, was the basic working condition for uniformed Border Patrol agents. They were pelted with bags and bottles of piss by gangsters standing on ladders at the fence. Cinder blocks crashed through the windshields of their trucks as they prowled the frontage roads looking for smugglers. But those four years in uniform taught Vargas two things: The first was how to track men who wished to go unseen. The second was that he never again wanted to wait around for his target to come at him.

So when he was promoted, in 2004, to a plainclothes desk job at a station near San Diego, the first thing he did was attach himself to investigators in the Anti-Smuggling Unit of CBP. He pumped them for ways to mine national-security databases, looking for felons who’d been jailed and deported, but who’d snuck back in with false papers. He picked up tricks for poking holes in statements from the felons they’d arrested for smuggling. “Anyone can tell a lie start to finish,” he says. “But make ’em tell it backwards and you find the holes. That’s when the truth comes out.”

Above all, he learned that the great detectives aren’t “solar-driven,” i.e., arriving at nine and leaving at five. On evenings and weekends, he’d prowl the web for open-source leads on fugitives. Anyone could be found, once you knew where to look. The key was sifting through traces, then putting in the time, sitting vigil on suspects’ houses after-hours. He’d go on to make CRIM Squad in his image: six guys who’d show up, no questions asked, to tail a narco’s car at 3 a.m. They all spoke fluent Spanish and could pass for sicarios — minus the gold Breitlings and Jesus pieces.

“We’d all done the cowboy stuff, chasing FTYs on I-5,” says Sito, the youngest — and most fearless — of the CRIM Squad agents, having served a brutal tour in Afghanistan. (FTY, or failure to yield, is BP shorthand for high-speed pursuits.) “But with Vargas, it was all about the intel-building. Debriefing every collar to get the next guy up the ladder, then doing surveils for five days straight.”

“Yeah, the hours were just stupid — but he worked ’em same as we did: four in the morning till whenever,” says Guru, the workout fanatic and know-it-all gun nut who could fieldstrip an M-4 blindfolded. “We were together so much, we turned the office into our dungeon. Kettlebells here, chinning bar there — and every fucking set was a contest.”

Vargas, an undersized nose guard in college, still looks like he squats 400 in his fifties. His parents, Mexican migrants, slaved for their sons and sent both of them into public service. Raised in a barrio east of Los Angeles, Vargas saw how thin the line was for brown-skinned boys. On this side, the ones who worked their tails off after school; on that side, the ones who flaked in 10th grade and wound up on the yard. But Vargas brought more than a grinder’s grit: He was also, by nature, a connector. Each morning, before work, he would cold-call different shops, chatting up the point man on an anti-gang task force or a higher-up at the FBI’s off-site. He wasn’t just friending cops and fishing for cases. He was also bringing goodies to share with other teams that were chasing after cartel hit men.

Among those goodies was something called TECS — an exclusive database of every person, vehicle, boat, plane, or shipment entering the United States through a port of entry. Even killers with forged IDs left footprints to follow: a time stamp of arrival; an alias to cross-check; a set of known associates to surveil. “There were Border Patrol detectives who’d used TECS to look out for returned felons — wife beaters, child molesters, that kind of thing,” says Vargas. “But we were the first to say, ‘Hey, there are cartel murderers here. Those are the ones we should be hunting.’”

We caught the worst of the worst. My kids know: If something happens to me, the first call is to these guys.

Back then, DHS was the only outfit that could file certain charges against narcos: illegal entry after deportation; illegal alien with a gun; human smuggling, etc. Any violation of immigration law could take killers off the streets at a moment’s notice. Better still, you could arrest perps without them even knowing that they were part of a larger sting. They’d think they were facing fed time for sneaking across the border with a gun and a fake ID. Their bosses and crews would think so, too, and go on about their business — till the task force or DEA dropped the hammer.

“They called it ‘walling off’: bringing pretext charges” while the long-term operation carried on, says Duncan. “That was very useful to teams like ours — and no one really did it before Vargas. There wasn’t a lot of sharing going on.”

Long after the failures of intelligence sharing that helped lead to 9/11, the three-letter law-enforcement agencies don’t play nicely together, guarding their territory fiercely. But Vargas had no use for parochial nonsense and would help anyone who helped him. Beat cops, staties, the Mexican CIA: He built the kind of alliances you could win a war with — though not, alas, the War on Drugs. They’ll still be fighting that one when the sea floods San Diego, and the waves raise all the dead in Mexicali.

JUST WEEKS AFTER clocking in as CRIM Squad chief, Vargas got pinged by an FBI buddy about a very odd kidnap in San Diego. The kidnap wasn’t the story, but its punchline was: The victim wound up captive in Tijuana. “The guy’s drinking at a bar and meets a girl who takes him home,” says Vargas. “Next thing he knows, he’s chained up to a sink, with a big red welt on his ass.” The welt, said Vargas’ source, was from an elephant gun — the kind used at zoos to dart big game. “That was all they told me, along with a name. The perp was some dude called Furcio.”

Usually, Vargas’ crew could take a nickname and get rolling, but Furcio was on no one’s radar screen. Still, Vargas turned over every rock: kidnaps were a menace in San Diego. “When the killing went over the top [in 2007], Mexico sent the army to Tijuana,” says Duncan, the task force leader working the AFO. “That put the clamps on narcotics coming in, so the gangs needed another source of income.” Mexican businessmen were snatched for ransom in Tijuana and San Diego. One of Vargas’ neighbors was targeted by the Palillos. That botched abduction ended in a firefight between their hit squad and a Chula Vista cop.

Vargas checked in with his cartel sources: There were three kidnap crews in San Diego. The scariest of the bunch were Los Palillos, motivated by vengeance, not profit. Back in the day, they’d been enforcers for the AFO, hurting anyone who crossed the brothers. Till one drunken night in 2003, when a Palillo punched an AFO in-law. The AFO retaliated by kidnapping and torturing a Palillo leader. The cops found his corpse wrapped in a garden hose; his crew hastily fled to San Diego. For the next four years, the Palillos terrorized that town, snatching AFO associates, holding them hostage, and, when they felt like it, returning them alive. Often, they got their ransom but killed the captive; they murdered 14 people in two states. “The AFO sent their hit squads here to try and take them out,” says Duncan, who led the Palillos investigation. “Either shoot them on the street or bring them south.”

Furcio led one of those hit-man crews. But in the meantime, he had to earn a living in San Diego; reports cropped up about people being plucked off the streets by men in a panel van. The victims weren’t gangsters, just random civilians held for sums in the low five figures. Nor did their non-cartel status lead their captors to spare them brutalities: They chopped off the fingers of a man and sent them to his loved ones as proof of their bad intentions.

Vargas first heard of Furcio in the fall of 2007. He expected to track him down in weeks, if not days, because that was how it went with his bloodhound crew. “We don’t do like the FBI, where they’re up on a wire forever,” says Sito. “We’ll hunt anyone we think might know you. We’ll put trackers on your mom’s car and tail her to church, if that’s what it takes to find you.”

For months, CRIM Squad members worked lead after lead, sitting on addresses from East Lake to Poway on tips from Vargas’ informants. Now, surveillance is not what you’ve seen onscreen: two cops hunkered in an unmarked car, chatting and wolfing fast food to fend off boredom. Instead, it’s one investigator in the back seat of his car, laying under a sheet perfectly still. Often, they’re in boxer briefs sweating it out, because the car and its A/C are off all day and there’s nothing but window tinting to fade the San Diego sun. “You pull in at 5 a.m. and lay there till nine, not moving while you piss in a bottle,” says Guru. “Nights are even longer, ’cause now you’re on crook time — and they don’t work steady hours.”

It took months, but CRIM Squad got a fix on its target — by way of a gangland slaying. In February 2008, Furcio was drinking with some friends at a condo in the Camelot Apartments. When the beer ran low, he sent the friends for more, tossing them the keys to his Cadillac. As they got in the car, a van pulled up. Three men with rifles opened fire. One of the friends fell dead. Another was abducted. He’d later tell the cops what the gunmen told him: Furcio was their target, and they’d botched the hit. They’d thought that was him in the Caddy.

“At this point, everyone’s looking for Furcio, figuring there’s a bloodbath popping off,” says Vargas. But Furcio went to ground after the botched hit, and the trail promptly stopped cold. The other feds moved on to fresher cases. Only Vargas kept a burner lit for Furcio while he and his squad were out chasing narcos. Case in point: their takedown of the Linda Vista-13. A subset of Mexican-mafia wannabes, they’d moved to San Diego as minors and been busted for cartel crimes as adults. Then, one of their members stabbed a Border Patrol agent; Vargas and his men were summoned. For six weeks, they surveilled gang addresses and caught them out with one thing or another. Fifteen gang members got jail time, then were deported back to Mexico for good. Their set dissolved and was never heard from again. “We wiped ’em off the face of the Earth,” says Sito.

Finally, that November, they caught up with Furcio, after a yearlong manhunt. Vargas got a tip from a friend at ATF; he sent Guru to sit on the address. “I had just put my sunshade up for [a long surveil]” when here came Furcio walking toward him. Guru called Vargas. Vargas called in backup, but they were 20 minutes south in traffic, so Guru tailed Furcio in his Cadillac with blacked-out rims. Furcio pulled off at the H Street exit and stopped at the AmPm mart. Vargas got there just as the backup roared up. Eight men in armor poured out of a van with rifles. Furcio saw them and turtled in his seat. He looked stunned when they pulled him from the Caddy and cuffed him — he surely assumed he was about to be killed.

Back at the station, feds lined up in Vargas’ office. The FBI, DEA, ATF, Group One: Everyone but the Secret Service wanted a crack at Furcio. But Vargas made the collar, so he went into the interrogation room first. He had all the leverage you could ask for with a perp. They’d found the elephant gun allegedly used on kidnap victims, plus his .45, false IDs, and fake-cop get-ups. But Furcio, a short, slight man in his thirties, didn’t even blink through rounds of grilling. He had a story for everything. The tranquilizer gun was “protection” for hiking in the desert; the .45 kept him safe in the barrio. Nor could Vargas charge him on behalf of kidnap victims: None of them came forward to accuse him. He wound up doing fed time for the guns and fake IDs, then was handed to the Mexican military for sweating. They went at him good and hard, but couldn’t break him, either. Released, he melted into the Tijuana streets — literally, per one expert’s guess. “There hasn’t been a peep from him in, what, 12 years?” says Vargas. “When a guy like that goes quiet, the first thing you think is: His teeth are in a barrel on someone’s ranch.”

IN THE MICRO-CULTURE OF COP LAND, word gets around when you catch a couple of high-end bad guys. By early 2009, Vargas was getting calls from the other top outfits in town. Dave Contreras, a boss with the Gang Suppression Team of the San Diego PD, asked for CRIM Squad’s help with Operation Stampede, a massive, task-force takedown of the Southeast Locos. “That set was out of control, just stone-cold killers: five bodies in 15 months in Lincoln Park,” says Contreras, who’s now retired but working a cold case in Los Angeles. “I brought in CRIM Squad ’cause those guys were regulators. The best bunch of hunters you ever saw.”

For that op, the hunt was tracking killers for months, then bagging them up just hours before a murder. “Because we were on wires, we knew when a hit was coming: We stopped at least 20 murders from taking place,” says Contreras. CRIM Squad would find the perp, surveil him for weeks, then sack him up as he left to do his dirt. One of those collars was a guy named Anthony Zendejas, whom CRIM Squad popped holding a Molotov cocktail and an incendiary device. He was on his way over to burn down the house of a rival gangster. Another was Pariente, an older gangster who ran guns to the AFO. He lived in an alley behind Lincoln High School and sold meth and semi-autos to minors. “His whole business model was hurting kids,” says Guru. “I loved bagging that guy: He was evil.”

Finally, on May 1, 2009, 40 cops and feds — including CRIM Squad agents — kicked down the doors at five addresses. They arrested 21 suspects and seized 14 guns that day, and confiscated 60 keys of coke and methamphetamine over the course of the operation. Five of the Locos were charged with murder. The rest went down for conspiracy to murder and other violent crimes. It was the bust of the decade in San Diego, wiping the Southeast Locos off the gangland map and liberating the blocks they’d held by force. Contreras, the task-force chief, wrote CRIM Squad commendations; he calls them the “best federal unit I’ve ever worked with.” That fall, they won the top state honor for cops who bring trafficking cases: the California Narcotics Officers Award. In hindsight, the certificate felt a tad premature for a crew that hadn’t faced its greatest test. They’d earn it, and then some, in the months to come. El Teo’s hit squad was coming north.

One day that fall, Vargas got a call from a DEA agent with the Group One Task Force whom I’ll call Nikki. She and her team were hunting El Teo and his merry band of sadists in Tijuana. By now, half of Mexico was chasing Teo: He’d turned Tijuana — and most of the Baja peninsula — into an abattoir. Thousands murdered since 2007; dozens of cops assassinated by his goons; Mexican-army checkpoints in every barrio. “He committed the cardinal sin of narco bosses,” says David Herrod, the case agent for the Group One Task Force. “He made things bad for business — everyone’s business.”

Group One had wires up on a couple of Teo’s lieutenants; what they needed was real-time intel on his movements. Nikki had a name for Vargas to chase: “Tigre,” Teo’s leg man in the States. CRIM Squad sifted through their intel cross-checks, searched every alias linked to Tigre, and found a car connected to a name. In less than a week, they tracked it to an address. Sitting on that house, they spotted Tigre in a car. “We had a cop stop him for a traffic violation; we didn’t want him knowing what was up,” says Vargas. Back at the precinct, Vargas walked in and wasted no time on the niceties. We know who you are and what you’ve done: You called in a hit on a TJ cop. To prove it, Vargas showed him Teo’s org chart. There, on the third rung, was Tigre’s name and photo. He crumpled, agreeing to spill his guts. Then his cellphone rang: It was Teo.

Tigre’s face went pale as he listened to Teo talk. By the time he hung up, Tigre had changed his mind; he wasn’t going out in someone’s crockpot. Enter Nikki, the Group One agent, with an offer of full protection. Tigre eyed her: Why should I ever trust you? She pointed to the poster on the wall behind her. It was the DEA’s Most Wanted List, bearing the photos of 32 kingpins and their capos. At the bottom was a phone number. Dial it, said Nikki. Tigre did so. Her cellphone rang.

“It was a mic-drop moment,” Vargas says. “The only thing he could do was sign the proffer. We not only got his phone but his total cooperation. Then we found the ledgers at his place.”

Those ledgers — which Tigre parsed for Group One — were far more useful than profit-and-loss sheets. They identified, by code, “who was who in the zoo”: the half-dozen or so narcos who spoke directly to Teo from either side of the border. One of them was a capo called “Timmy.” He lived part time in San Diego, worked in Tijuana — and killed several TJ cops on Teo’s behalf. No one knew Timmy was on U.S. soil till Vargas called his sources in Mexico. The PEPOS, or state police, had a file on him that they hadn’t bothered to share with Group One. That stonewall was standard procedure, says Herrod. “The Mexican cops wouldn’t help us out unless we showed them an actual indictment.” But everyone in TJ helped out Vargas. He’d spent years going down there on his own dime to liaise with the state and city police and to train up street cops in intel tactics. With the PEPOS’ information, he put an alert out on Timmy at all the border crossings. Weeks later, he got a call from Customs agents; they had Timmy in holding.

Timmy poured his heart out at the Group One off-site. In exchange for a stipend and a new place to live, he’d help them locate Teo and his lieutenants. No one at Group One would give me specifics on the nature of Timmy’s assistance: He’s still a “protected informant” 12 years after Teo’s capture. What agent Herrod did convey was that their “actionable information” had been “useful” in the takedown of Teo’s gang. In exchange, Timmy got the “Sammy the Bull [Gravano] deal,” as Vargas calls it, sneering. “Umpteen murders and no time served. Plus a pat on the back from Uncle Sam.”

Days later, he met Timmy himself at a mall in San Diego. He showed up armed, expecting the unexpected. What he got was a small, stubby man in a faux-hawk, mouthing the standard mob subjunctives. Teo told me this … Teo told me that. What’m I gonna do, bro — it’s Teo. “Not an ounce of remorse: just an evil little shit who made my skin crawl,” says Vargas. That night, after taking the long way home — he always changed his route after a face-to-face with narcos — Vargas got down on his knees and prayed. “I asked God, ‘Please! Keep my wife and kids safe — and why are there people like that in the world?’”

WITH NO SMALL HELP from CRIM Squad, El Teo was arrested at a La Paz address in January 2010. Dozens of men in armor crashed his door; Blackhawk gunships circled overhead, anticipating a shootout with his men. But faced with “overwhelming force,” says Herrod, the butcher stood down without a peep. A month later, his top lieutenants were caught in Baja. His organization splintered, his stew-maker was jailed, and a fragile peace broke out in Tijuana. “Murders came down big-time; we set a record low that year,” says Seven, the former police chief of the town. Tijuana’s economy roared back, and so did its nightlife: “People weren’t so scared of being shot,” he says. The biggest cheers went up from TJ’s cops, he adds. “He killed 60, 70 police in two years.”

The response among U.S. cops was rather more restrained. The United States attorney in the Southern District of California failed to indict Teo for mass murder. That enraged Herrod and his Group One agents — but it didn’t surprise them at all. “After the AFO trials, they’d made it pretty clear they were sick of trying cartel cases,” he says. “Too much time, too much manpower, too much money invested. Better to just let Mexico lock ’em up.” Herrod can’t confirm that Teo was charged in Mexico, either, though he has been “indefinitely detained,” says Seven. “They’re supposed to charge you within six years, but sometimes they forget,” he says, laughing. Such is the state of that judicial system that even an ex-police chief can’t be sure that a genocidal ghoul has been sentenced.

CRIM Squad found little to rejoice in Teo’s fall. In fact, they weren’t even told that the arrests they’d made were material to his capture. “Eventually, I heard something about we’d played a part, but no one ever reached out and said so,” says Vargas. “We were soldiers bagging soldiers. They never told us more than we had to know.”

The only shine CRIM Squad got was from their peers in San Diego. News of their exploits was bannered large in bulletins the regional office put out. Young agents stopped them in the hallways: Holy shit! You’re the guys that sacked Furcio! The honor that mattered most, though, came from CBP: It founded a weeklong school in CRIM Squad tactics. Called the SIG Academy, it was mandatory coursework for Border Patrol investigators in San Diego. The chief instructors: Vargas and his squad. “We taught everything from intel to mobile surveillance.” To be sure, those are givens of investigative policing — but till CRIM Squad, no one did that at CBP.

They forever changed the game there, then went their separate ways. In 2010, CRIM Squad joined a bigger unit, the Border Crime Suppression Team. Vargas stayed on to supervise his section before drifting off to intelligence operations. His men jumped onto task-force units with the FBI and DEA. “You’re attached to details with a bunch of shirt-and-tie guys; when that clock hits five o’clock, they’re like, ‘Seeya!’” says Sito. “It’s a shock for a minute, but at least you see your kids. And to be honest, I was fried when we split up.”

Late last summer, Vargas convenes the crew at a cantina in Otay Mesa. It is a curious spot for federal drug cops to dine: a high-end Hooters knockoff catering to narco-juniors and the surgically souped-up women they prefer. Seven of us sit there, sipping Don Julio and recalling the demons of yore. There was El Yeyo, the sad-sack TJ cop conscripted by Teo to fetch corpses to a guy called El Pozolero, who’d melt the bodies at his ranch. Vargas tracked Yeyo to an ex’s in south L.A., then handed him off to the Mexican police. In his confession, Yeyo admitted to heinous acts with deadpan indifference. “But then he’s asked if he was there when they cut a guy’s dick off,” says Vargas. “And he goes, ‘Yeah — but I only held the camera!’”

So it goes for the best part of three hours. The squad members recount the killers they caught at their day jobs, including one guy working at a Cheesecake Factory, and a Sinaoloa hit man who hid in the States after fleeing Mexicali in 2002. And then there was El Chan, the notorious cop turned capo who had made his bones whacking Chapo’s henchmen. When CRIM Squad caught up to him in 2010, he was laying low in Eastlake with two very attractive sisters, living the throuple high life in a McMansion.

“A Mexican who thought he was Mormon!” Sito cackles. “Big Love in Spanish — ‘Grande Amor’!” CRIM Squad revoked Chan’s B-1 visa and pushed him through the gate at Whiskey Two. Hours later, Chan was attacked by his rivals in Tijuana, touching off a two-day shootout. His cousin was among the six slain, along with a schoolgirl hit by stray gunfire.

For five years, these men had been part of something rare: an elite unit led by a brilliant cop who got complete buy-in from his squad. “They were the best — and worst — years of my life,” says Sito. “This man worked us so hard, I’d pull up at my house and just nod out in the front seat.” “I ended up divorced because of the hours,” says Guru. “Not that I’m blaming the job for that. These guys were at my wedding, so she knew what she was in for.” The Squadders drew so close, they’d spend their free time together. There were drunken Friday dinners at Vargas’ house, the wives inside at the kitchen table, the cops on the patio, laughing their way through cases of Tecates. The ferocity of their mission; the foxhole esprit de corps; that sense of doing truly important work — for half a decade, these men fell in love with their jobs and, to no small degree, with one another. “We were lucky enough to say, ‘We caught the worst of the worst,’” says Sito. “And to this day my kids know: If something happens to me, the first call they make is to these guys.”

In light of their achievement, it seems like bad form to ask what all their labors had delivered. Weeks before that dinner, Tijuana went up in flames: Men in balaclavas stormed buses and vans and put them to the torch all over town. For three days, residents locked themselves indoors, waiting out the cartels’ temper tantrum. “The bosses weren’t happy and want to send a message: too much policing,” says Seven, who left his post to work a detail in Immigration, after more than one attempt on his life. The murder rate has soared to peak-Teo levels. Chapo held the plaza following the fall of the AFO, but his capture in 2016 put the town up for grabs — and narcos, like nature, abhor a vacuum.

I speak to Vargas shortly after the Tijuana burnings. He’s sitting on the veranda of his very handsome house, a few miles north of the border fence. He can’t see the smoke but he can smell it, he says. “My next-door neighbor’s a failed nation,” he says. From his tone, it isn’t clear which nation he has in mind: Mexico, the world’s lead supplier of narcotics, or America, the world’s lead consumer.

Best of Rolling Stone

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance