Home DNA tests may affect insurance, employment

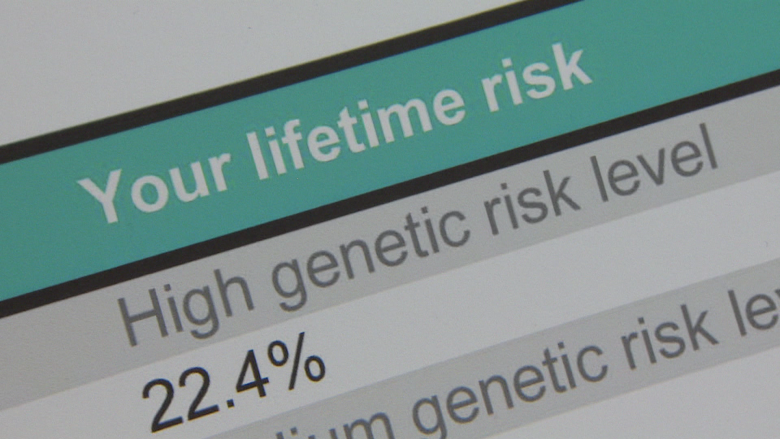

Curious about what your DNA might say about your medical future? Genetic tests may tell you if you are more likely to get sick, but taking the tests could expose you to risks you weren't expecting.

While an increasing number of test kits allow you to screen for diseases in the privacy of your home and send your samples by mail, there's little protection if you want to keep those results private.

Unlike other countries including the U.S., U.K., and Japan, Canada has no legislation that protects you from having to disclose your test results to employers and insurance companies, despite a promise by the federal government in 2013 to introduce protective measures.

And a bill currently before the Senate has lost some of its key protections, including prohibiting anyone from forcing you to take a genetic test or reveal the results.

"Canada is one of the only countries in the western world that doesn't have laws to protect the integrity of your genes," Senator James Cowan, the Nova Scotia Liberal who introduced the bill, told CBC Marketplace co-host Erica Johnson.

"There's nothing to prevent an employer or an insurer or anybody else providing any other kind of service, about saying, 'Have you ever had a genetic test? And if so, what are the results of that test?'" he said.

Marketplace investigated home genetic testing kits and found that kits screened for a limited number of diseases and the results and some of the interpretation varied widely between tests from different companies.

- Watch the full investigation, Gene Genie, Friday, April 3 at 8 p.m. (8:30 p.m. in Newfoundland and Labrador) on CBC TV and online.

'Jolie effect'

Genetic testing looks at DNA taken from saliva or blood, screening for markers associated with an increased risk of diseases or conditions such as heart disease or cancer.

Genetic screening is becoming increasingly mainstream, and greater awareness is fuelling interest, sparked in part by Angelina Jolie's public disclosure of her genetic risk for developing breast and ovarian cancer.

In 2013, Jolie wrote about her decision to have both her breasts removed, and in 2015, she spoke out about a similar decision to have her ovaries removed. Genetic testing revealed that Jolie carries the BRCA1 genetic mutation, putting her at an 87 per cent risk of developing breast cancer and a 50 per cent risk for ovarian cancer, according to her op-ed article in the New York Times.

In addition to screening by a doctor or at a hospital, direct-to-consumer tests have become popular options, with most home kits from companies like 23andMe and EasyDNA costing between $200 and $500.

Information important to assess risk

But you might not realize that if you have genetic testing done, you may be obligated to reveal that information to your insurance company.

According to the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association (CLHIA), "Where genetic testing has been undertaken and a person is aware of the results and subsequently applies for insurance, the insurer needs to be made aware of relevant and material information derived from the test in order to properly assess the risk."

A CLHIA position statement continues, "This policy is based on the general principle that an insurance contract is a 'good faith' agreement. Both parties have an obligation to disclose any information that may be relevant to the contract so that it can be entered into on an 'equal information' basis."

But whether home DNA test kit results must be disclosed is less clear.

The association declined to be interviewed for the Marketplace investigation.

In a statement, Wendy Hope, CLHIA vice president, wrote: "Direct-to-consumer (DTC) tests are relatively new and each company is working to assess their reliability as they encounter them during the underwriting process. We have not developed an industry position on the value of such tests."

'Instances of genetic discrimination'

Cowan introduced the Senate bill, "An Act to Prohibit and Prevent Genetic Discrimination," in 2013. The bill would prohibit any entity from forcing someone to undergo genetic testing as a condition of getting a job or receiving a service, or from forcing individuals to reveal test results.

The bill also would amend the Canadian Human Rights Act to protect individuals from genetic discrimination.

Later that year, in the Speech from the Throne, the federal government committed to introduce measures to "prevent employers and insurance companies from discriminating against Canadians on the basis of genetic testing." The government has not yet introduced any new legislation.

Cowan's bill now would protect only federal employees, because the Senate's Conservative majority removed most of its key provisions.

It would not protect most Canadians from having to reveal results to employers or insurance companies.

"People should be able to make a choice about whether or not to get genetically tested without worrying about whether it's going to have an effect on their insurability or employability," Cowan said.

"I think there are instances of genetic discrimination in Canada, both with respect to employment and insurance. And we're the only major country in the Western world that doesn't have some sort of protection," he said.

"This is not about asking about your current medical situation. We're talking about testing that would indicate to you the likelihood that you might sometime in the future develop a particular condition or disease."

"People should be able to make a choice about whether or not to get genetically tested without worrying about whether it's going to have an effect on their insurability or employability."

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance