‘I don't like acts of dishonesty by the state’: Jolyon Maugham QC on Covid cronyism

Over the past few years, Jolyon Maugham QC, founder of the Good Law Project, has become an unmissable presence on Twitter. But unlike most keyboard warriors – anonymously vocal about Brexit, trading memes over mask-wearing and gender politics – he has only ever seen the social media platform as a means to an end. “I really don’t like this phenomenon of disinterested observers pointing out things that are going wrong,” he says. “I want to be in the club of people who actually put skin in the game to make it better, rather than merely making clever observations from the sidelines.”

Related: Boris Johnson ‘acted illegally’ over jobs for top anti-Covid staff

The most visible expression of this commitment was the legal case that Maugham brought, in August 2019, along with Joanna Cherry MP, that saw the prime minister’s attempt to “prorogue” parliament overturned, stunningly, first in the Scottish courts and then by the supreme court. While the Twitterati had clutched their virtual pearls about Johnson’s trampling of democratic norms, Maugham saw the gaps in the legality of the government position and got swiftly to work on a strategy to expose them.

The Good Law Project was in part set up to harness some of the righteous outrage that Maugham saw on social media. It relies on crowdfunded donations of £10 or £20 from thousands of sympathetic supporters to pursue its cases – £200,000 was raised to fund the prorogation action. That case file is now focused very directly on the culture of cronyism and the highly secretive use of billions of pounds of public funds that appears to have infected every corner of the government’s response to the pandemic.

Maugham has, over recent months, launched crowdfunding for a legal challenge to the appointment of Dido Harding – wife of Tory MP and government “Anti-Corruption Champion” John Penrose – as head of the newly formed National Institute for Health Protection, without any interview process or open competition. It has ongoing proceedings aimed at answering the question “Just how does public money end up in the pockets of Cummings’s friends?” Separately, last week it opened the latest in a series of cases against the Department of Health to shed light on the award of PPE contracts worth more than £250m to Saiger, a Florida-based jewellery company with no experience of supplying PPE. That involved a £21m payment to a middleman – a contract offered without any advertisement or competitive tender process.

The latter cases form part of the material behind this week’s explosive National Audit Office Report, which revealed how suppliers with favourable political connections have been directed to a “high priority channel” for government contracts, giving them ten times more chance of success. The report appears to vindicate what has been a stubborn gathering of evidence by Maugham and others over many months.

When he set up his project, at the beginning of 2019, Maugham’s colleagues at the bar told him that he was “setting sticks of dynamite” under his lucrative tax law practice, “and blowing it to smithereens”. Maugham, 49, found that idea not only liberating but also cathartic. It gave him a personal outlet for a widely shared mid-life anger about the drift of our politics. From the end of this year he will work at the Good Law Project full time and draw a salary that will be “about one-twentieth” of his recent take-home from his chambers. The Good Law Project has a staff of 10, which he plans to expand. “The fact is I really, really don’t like acts of dishonesty by the state,” he says, of his motivation. “I don’t like the government misleading the public. It feels to me, every time I hear it, like a direct attack on democracy. And that was really winding me up.”

Having spent the Brexit years in intimate study of the ways and means of the current government, Maugham’s antennae started to twitch earlier this year when vast amounts of public money began to be thrown at the catastrophically delayed response to the pandemic. In March and April this meant frontline PPE. “To begin with, we spent seven or eight thousand pounds, a lot of money for us, commissioning very detailed advice about when doctors and nurses denied protective equipment could refuse to treat patients without being sued,” he says. “We were worried that they were being put under immense, improper pressure by politicians and managers.”

It was in early May though, when details emerged of the first contracts designed to plug that gap, that Maugham really started to sit up. The Good Law Project had just fired off a legal challenge that sought to force the government to hold a rapid public inquiry to learn lessons of the pandemic in time for the second wave, when he got talking to Billy Kenber, a journalist from the Times, about some of those PPE contracts. One of the biggest had gone to a company called PestFix, which, Maugham learned, had 16 members of staff, cash assets of £19,000 and a speciality in supplying products to prevent pigeons from roosting on buildings (it acts as an intermediary and its founder calls it a public health supply business). “We were slightly staggered that this tiny little company that ran the website pigeonstop.co.uk had won a £108m PPE contract.”

He called up a “suitably dour lawyer, who I’ve known for ever,” Jason Coppel QC, a leading procurement barrister. They talked through what it would look like to bring a legal challenge to discover more about how that PestFix contract had come about. “And the litigation came out of that, really.”

To give that litigation more bite, Maugham contacted a couple of doctors’ associations. One of them was EveryDoctor, another crowdfunded campaigning organisation that has grown sharply in membership over the past year. Dr Julia Patterson, one of its leaders, was also following the PPE crisis very closely. For two months she had been hearing horrific stories from her members, she recalls, about how, while there was a continued scramble for adequate protection, friends and colleagues were dying. “I’m a psychiatrist, I’m used to hearing desperate stories,” she says, “but these emails were some of the most hopeless things that I have ever read.”

Waiting a couple of years for the inevitable public inquiry didn’t seem enough for Patterson. EveryDoctor itself had partly grown out of a Facebook group, the Political Mess, that she had established, in which healthcare professionals could share information. “What we were noticing was that there was a total dissonance between the speed with which clinicians have to respond to situations at work and how our professional bodies behave, which is mostly in established committee meetings, where things take months to decide.”

So when Covid arrived, the immediate thought at EveryDoctor was, “this is going to get bad really quickly – and no one is going to move fast enough to hold the government to account”. Patterson watched the government falling over itself trying to control the media cycle, releasing information without proper checks, launching “world-beating schemes” while on the ground little was changing.

While EveryDoctor helped to assemble that real-life strand of testimony for the Good Law Project’s PPE case, Maugham continued to investigate those companies that had won contracts. In July he tweeted what he called “the most extraordinary thread I’ve ever written”, which revealed how a company called Ayanda Capital Ltd had won a £252m contract to supply millions of face masks to the Department of Health in April, at the height of the pandemic. The firm specialised in “currency trading, offshore property, private equity and trade financing” and was based in Mauritius.

Maugham discovered that this deal had been brokered by a man named Andrew Mills, then one of 12 advisers to the Board of Trade, chaired by international trade secretary Liz Truss. According to his LinkedIn profile, Mills had been a “senior board adviser” to Ayanda Capital since March. (Mills states that his position at the Board of Trade played no part in the award of the contract.)

“What could possibly go wrong?” Maugham wondered. Plenty. The Ayanda contract included an order for 50m high-strength FFP2 medical masks, which on arrival were found not to meet NHS standards (Ayanda maintains that they adhered to the specifications they had been given). The FFP2 masks had elastic ear-loops, not straps that went around the back of the wearer’s head as required. The Good Law Project further discovered that Pestfix, the stop-the-pigeon company, (its founder calls it “a public health supply business”) had actually been awarded PPE contracts worth £313m.

Last week at prime minister’s questions, Keir Starmer raised the question of Ayanda Capital’s role in PPE procurement. The prime minister ruffled his hair and made baffled grunts before suggesting that the leader of the opposition was falling short in his patriotic duty to leave unscrutinised the efforts of the private sector in responding to the crisis. Maugham was slightly annoyed that the Good Law Project did not get a namecheck.

It is Maugham’s contention – disputed by government and the companies concerned – that the circumstances not only reveal gross ineptitude, but also a pattern of procurement that at the very least falls gravely short of required legal transparency. The case against the government over Ayanda and PestFix is scheduled for hearing in February – the Saiger case may well be added to that action. Maugham is pushing for funding for a separate case, which will examine the mass-testing programme, Operation Moonshot, which has an eye-watering promised cost of £100bn – “yet we know nothing about who has made the decision to spend it, or with what safeguards, or with whom, or why with these counter-parties.”

Stewart Wood, Lord Wood of Anfield, former adviser to Gordon Brown during the financial crash and fellow in the practice of government at Magdalen College Oxford, is a board member of the Good Law Project. He agreed to work with Maugham because he knows at first hand that “our unwritten constitution with gentlemanly rules is fine until someone comes along and doesn’t observe the rules”. When I spoke to him, Wood suggested that as a result of the prorogation case last year, the Good Law Project could become a significant player in politics. “It’s like a band that had a novelty hit, but then wanted to get on and do the stuff that it really cared about,” he says.

Critics of Maugham’s approach, and there are many, accuse him of the antique offence of “barratry”, or vexatious litigation – drawing the courts into consideration of questions that they do not traditionally answer. Wood suggests, rather, that if ministers with a large majority are going to stand up in parliament and announce that they are breaking laws, then “the courts can be used not in place of parliament but to clarify what you might call the ‘wild west’ parts of our regulatory system. All we are asking for is rules and transparency.”

At the heart of this issue, Wood says, is the fact that in the midst of this pandemic the government has essentially invented a new centralised entity, the Cabinet Office, “which does not have any scrutiny in the parliamentary system. The government are suggesting that scrutiny should be suspended in a crisis; we think they should be doubly enforced.” Billions of pounds are being spent and huge decisions are being made, he says, in a kind of governmental “black hole”.

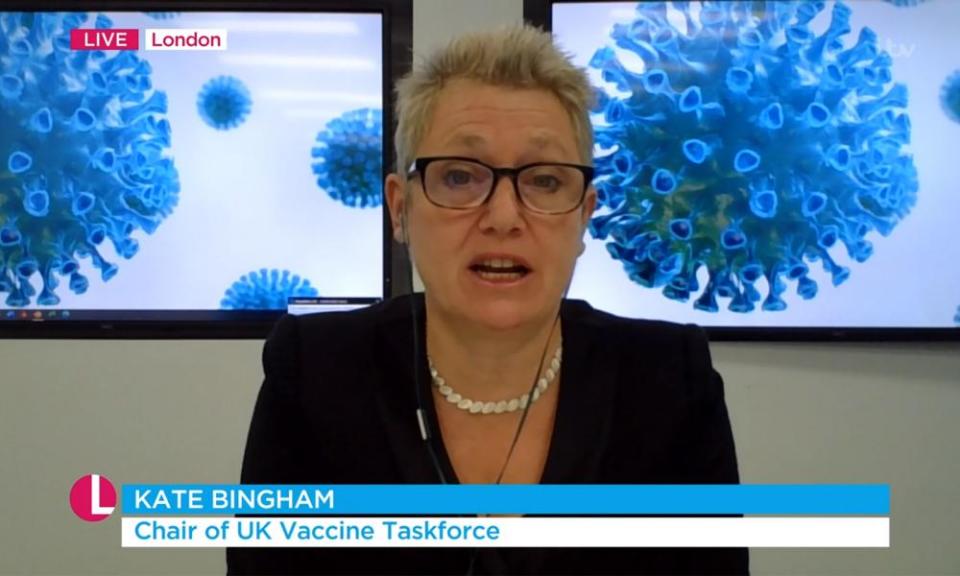

The £670,000 spent on PR consultants by Kate Bingham, the Tory insider appointed without formal process as “vaccine tsar” is one example among many. “It may be there are good reasons why these contracts were awarded, but there is not even an attempt to provide any case whatsoever. When [ministers] are pressed they immediately go to the ‘lefty lawyers are trying to undermine Britain’ argument”, Wood says.

Over the Brexit years – Maugham’s cases include defending the rights of British expatriates in Europe, a case to clarify whether the Brexit process can be reversed by Parliament, and the successful legal challenge to unlawful referendum spending by Vote Leave – Maugham believes that he has gained unusual insight into the strategies of Dominic Cummings. “Certainly, post-referendum, he and I were often chatting on Twitter,” he says. “He had, initially, a sort of opponents’ respect for what I was doing. But as we became more and more inconvenient, Cummings became more and more short-tempered. So he started accusing me on his blogs of being dishonest. He tried to crowd-source a referral of me to my professional regulator. If you’re sitting across the chessboard – I don’t want to heavily elevate my importance – but if you’re watching somebody and engaging with them, over a period of time, you do get a sense for how they operate.”

Maugham believes, without evidence, that Cummings was instrumental in briefing against him and his work to the BBC. Certainly it is striking that, over the past four years of wall-to-wall Brexit talking heads, there appears to have been an unexplained ban on invitations to Maugham, though he has been a pivotal figure in many of its debates. Only the second occasion on which he has ever been interviewed by the Today programme came earlier this year after what his office has learned to call TIWTF: the incident with the fox.

On New Year’s Day, Maugham had taken to Twitter to announce that, hearing a kerfuffle in his hen-house, he had gone out to his garden hastily clad in his wife’s kimono, and killed a fox that had become trapped in chicken wire, with a baseball bat. This ill-judged admission brought down a huge storm of outrage on Maugham. Enemies in the press, and critics on social media, seized on it as delicious evidence of his entitlement and cruelty. Though an RSPCA investigation concluded that Maugham had done no wrong, and that the fox had been killed swiftly, that didn’t stop the death threats against him.

In early March, the BBC invited Maugham on to talk about his experience of that social media harassment in light of the death of TV personality Caroline Flack. Mishal Husain surprised Maugham by opening that interview not with any reference to Flack, but by laying out in graphic terms how Maugham had “beaten to death” a fox, before going on to ask if his experience of subsequently being threatened by an internet mob might give him pause before attacking Brexiteer opponents in government.

Maugham’s lawyerly voice wobbled a bit in response – “I was sitting in the studio next to the chief rabbi, who was on Thought for the Day,” he recalls, “and I was trying to hold back the tears, actually, because the whole thing was still very, very raw for me.” Even so, he summoned enough presence of mind to argue that while journalists pulled back from “speaking truth to power” and scrutinising government, he would go on trying to fill that gap.

You don’t have to be much of an armchair psychologist to see the ways in which Maugham was born to that vocation. He knows the ways of the English establishment, but is resolutely not of it. In a response to a typically ill-informed sneer from the far-right provocateur Katie Hopkins labelling him “the son of an old Etonian”, Maugham set out this background in a piece for the Guardian. He was born in 1971 to an “impressionable young woman studying sociology at North London Poly”, who had a brief affair with David Benedictus, then famous as the writer who had exposed the snobberies and sadism of his Eton education in his novel The Fourth of June, and was subsequently producer of Radio 4’s Book at Bedtime. Maugham has the letter his mother wrote to Benedictus. “I do not expect you to marry me,” she said, “but you need to know I am pregnant.” That letter is kept on a shelf in his office next to carbon copy responses from his father’s lawyers. “Our client denies paternity,” they say, “but will make a nuisance payment of £5 a week until she marries.”

When his mother graduated, she emigrated to New Zealand with her parents and one-year-old Maugham. She married a man she met at a teachers’ training college, who adopted him. At 16, he fell out with his parents and they kicked him out of the house. He took a job cleaning at a girls’ school and moved in with a “depressed bachelor in his 50s who vacillated between unsuccessful ventures with prostitutes and passes at me”.

After finishing school, Maugham came to England and stayed with his maternal grandfather in the north-east. He met his natural father for the first time, and Benedictus pulled in some favours to get him a clerical job at the BBC. From there, having written a play that was accepted by Radio 4, he won a place to study for a law degree at Durham University.

Every line of that potted autobiography in the Guardian seems revealing of how Maugham might now be moved to uncover uncomfortable truths. He has maintained a distant relationship with Benedictus, who reminds him, he says, of Boris Johnson – “that same Etonian thing”. He is reconciled to a “loving relationship I would never have thought possible” with his mother and stepfather, but only after “several years with a brilliant psychotherapist, Paula Barnby, who led me to what I can only describe as an epiphany”.

When we read these stories, our default is to assume it’s not as bad as it looks, there will be some innocent explanation

In our conversations, Maugham referred to himself a couple of times as “a Kiwi iconoclast”. He accepts that maintaining that rebellious self-image while standing in a tweed suit outside the central criminal court and enjoying a tax lawyer’s salary might grate with some people. “I’m a middle-aged, married QC. And so my ability to pretend to be an outsider is conditioned by those realities,” he says. “But I do remember the 16-year-old who was homeless. I remember my sense of outrage on arriving in the north-east of England, at the divide between the haves and the have-nots. I remember being really angry listening to Radio 4, staggered by just how complacent the English middle class at rest was.”

The baby who was raised on “nuisance payments” is not about to go easy on such complacency. Does he believe he can undermine it in the courts?

“I was asked this question by a German public service broadcaster,” he says. “They look at what’s happening here, as do my relatives in New Zealand, and are totally flabbergasted. And the question was put to me by the German TV producer was: ‘Why is it that the German media thinks all of this behaviour by the British government is shocking and the British public seems not to care?’ I had to put it quite delicately, but I said: ‘I think in Germany, you know what it’s like for government to do profound wrong. And in England, we don’t, necessarily.’”

For much of this year he has been dismayed at the reluctance of large parts of the media to share his litigious anger about government secrecy. In recent weeks, he has sensed that opinion shifting. Even the Daily Mail, which led the hounding of “the fox-killing barrister”, has started giving in-depth coverage to the Good Law Project’s procurement findings, suggesting a change of editorial heart as to who or what might actually represent “the enemy of the people”.

Such shifts will not have gone unnoticed in government. Last week Maugham revealed the results of more freedom of information requests, which exposed a desperate behind-the-scenes paper trail, involving the army and the Department of Health, to assemble some vestige of a defence for another PestFix contract. He is confident that by the time of the hearing next February, many more such cases will have surfaced.

“When we read these stories, our [British] default is to assume that it’s not as bad as it looks, there will be some innocent explanation for it all,” Maugham says. “And so we sort of put it in the drawer marked ‘to worry about later’.” That is resolutely not his style.

With the news last week of the departure of Dominic Cummings and the promise of a “reset” of Johnson’s government, I wonder if Maugham believes that the culture that resists scrutiny will change?

He is not convinced, particularly in light of the footnote that Cummings will continue to “work from home” on Operation Moonshot. “The harm that is done when someone shoves cultural norms around truth-telling and governance off a cliff, isn’t undone if you push him off after them,” he suggests. “It will take a concerted effort to reverse that harm – and as yet there is zero evidence of that intention.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance