The China dilemma: U.S. CEOs face whiplash and tough choices as tensions mount

The scale of the raids was modest. Their psychological impact was huge.

Last March, Chinese authorities shut down the Beijing office of a U.S. consulting firm, Mintz Group, detaining five employees for 24 hours. A few weeks later, authorities visited the offices of another American consultant, Bain & Co., reportedly seizing phones and computers. Months later, a Beijing municipal department said Mintz had carried out “foreign-related statistical investigations” without obtaining approvals. The Bain visit remains unexplained. At least two executives of U.S. companies, one from Mintz and one from the risk and advisory firm Kroll, have been put under exit bans; they cannot leave China.

The events sent a chill through the hundreds of U.S. companies doing business in China. Before Moody’s Investors Service downgraded China’s credit rating in December, the Financial Times reported, it advised staff not to come to the office that week. “Everyone knows why,” a China-based employee told the newspaper. “We are afraid of government inspections.” Today, the CFO of a U.S. company doing business in China wonders, “If we send in auditors to audit our business there, are they in danger of being detained?” “Fear is rampant,” says a high-level executive at a U.S. business services firm that operates in China. “No one wants to talk about what they’re thinking or what they want to do.”

Three years ago, all of this would have been unimaginable. For decades China welcomed U.S. companies with open arms and generous incentives, part of the nation’s efforts to convert to a market economy. Now, for many of those companies, the relationship has become uncomfortably icy. The shift reflects broader, rising tensions between China and the U.S.—tensions that include not only geopolitical clashes, but also economic conflicts with world-changing implications. And as China’s homegrown industries increasingly compete successfully on a global level, the battle for market share is a new front in the superpower rivalry.

That rivalry is becoming hotter in both actions and rhetoric. Beijing now routinely sends military planes into the airspace of Taiwan, a U.S. ally, asserting more loudly its long-standing territorial claim to the self-governing island. That conflict could heat up now that Taiwan has elected a president, Lai Ching-te, who vows to defend the island against Chinese threats. The U.S. House of Representatives, meanwhile, has established a Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party; the panel declared in a recent report that the CCP “has pursued a multi-decade campaign of economic aggression against the United States.”

China’s government in turn argues, as it has for years, that Washington has launched trade wars and has unfairly subsidized many U.S. industries—including with recent legislation that backs makers of semiconductors, aerospace technology, electric-vehicle batteries, and other goods.

For many U.S. companies, the environment in China has turned dark and threatening. A strict data privacy law enacted in 2021 prevents some ships from broadcasting their locations or cargoes. China last year barred many Chinese organizations from buying products made by the U.S. company Micron Technology, saying they were not secure. China’s counterespionage law, expanded last year, invokes national security in new language so broad that the U.S. State Department warned U.S. companies they could risk punishment by conducting ordinary business. Meanwhile, the two nations are increasingly trading tit-for-tat sanctions. For example, in October the U.S. imposed controls on the export of advanced semiconductors to China; in December, China curbed exports of graphite, a central element in electric-vehicle batteries, to the U.S.

The shift is profoundly influencing the world’s most important bilateral relationship, and businesses in both countries are suffering the consequences. But U.S. companies, having invested far more effort and money to compete in China than Chinese companies have in the U.S., are particularly vulnerable as the business climate changes.

How are U.S. business leaders responding to the new reality? To find out, we interviewed four dozen CEOs, CFOs, and board members of U.S. companies doing business in China, plus other China experts and consultants. Most of them insisted on anonymity so they could speak candidly. Nearly all the interviewed businesspeople are lowering expectations and planning to bring capital out of China. But at the same time, they’re adapting to the new environment and trying to stay in business there as long as possible. Their attitudes ranged from wonderment to grim perseverance to bafflement about what to do next. Many are braced for more surprises.

The consulting-firm raids continue to stun executives who spent decades building businesses and relationships in China. Some feel they face personal risks as well as business risks. A U.S. CEO who has overseen Chinese operations for multiple companies—he estimates he has visited 1,000 Chinese factories—says he has not traveled there since the pandemic. Would he go today? “I have no reason to believe I would be targeted,” he says. “But the partner of our U.S. law firm who’s based in Hong Kong says, ‘You should not go. I don’t want to be the one negotiating to get you out of there.’ ”

The newly hostile environment is rewriting corporate plans, as surveys of U.S. companies in China show. When the U.S.-China Business Council polled its members last summer, record-high percentages reported unprofitability, reducing or stopping investment in China, and moving or planning to move operations out of China. For the first time in the poll’s 20-year history, the No. 1 issue affecting respondents’ five-year outlook was geopolitics.

The deteriorating business environment seems like a strong case for leaving. “The vast majority of companies are trying to figure out how to reduce their supply chain from there, manufacturing there—everything that has to do with coming out of China, they’re trying to reduce or eliminate as fast as they can,” says the recently retired CEO of a company doing all those things. Even so, most U.S. companies are caught in the new China dilemma: Dissatisfied and fearful though they may be, they feel they can’t afford to leave anytime soon.

The problem begins with why they are there. It’s no longer because of low labor costs; those costs have steadily risen in China in recent years. These companies are in China because they’re relying heavily on Chinese-made products, on the vast Chinese market, or frequently both. As one CEO tells Fortune, “I’ve got 20% of my business in China. I can’t get out.”

They feel chained to China because, like it or not, its products frequently offer the best combination of quality and cost in their industries. Consider an extreme case: Huawei, which makes equipment for telecom companies. Much of its gear is banned in the U.S. and several European countries because of fears that it could be used to spy on communications and send information to China’s government. (Huawei has repeatedly denied that its products could be used in that way.) Still, Huawei is the largest player in its industry by far because in markets where it’s welcome, it very often wins. A recently retired top executive at a global telecom company says, “I’m not an expert in politics, but they produce superior technology. Today Huawei will outperform any vendor in terms of cost, quality, speed of delivery, and service operations, hands down.”

Multiply that example across the economy. China makes all manner of intermediate industrial products that Western companies buy—bulk antibiotics, engine parts, 3D printers, polyester fibers, pharmaceutical ingredients, and countless others. If U.S. companies bought those components elsewhere, they’d struggle to compete. The recently retired chief of a U.S. heavy equipment manufacturer says that’s why he kept buying Chinese parts even after the environment turned unfriendly. “It’s not because I love China,” he says. “It’s because that’s the only place I can buy a given part at anything close to the price I have today. That’s a big problem.”

Separately, many U.S. companies feel they can’t leave because they gain powerful advantages by selling their Chinese-made goods in the uniquely vast Chinese market, reaping significant revenue and saving money through huge economies of scale. They can also export those products to the U.S. and other countries under their own brand names.

For years this multipart system worked great for both sides. It still works for many U.S. companies. The problem is that, increasingly, China doesn’t need those companies anymore.

In China, “the door opened to foreign participation for very strategic reasons,” says Kenneth DeWoskin, professor emeritus at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business and a longtime China consultant to U.S. companies. “Those reasons are inbound foreign direct investment capital, technology, and immediate access to foreign markets.” With each of those elements, China now needs much less U.S. participation, because many of its companies have achieved the competitiveness and scale to do without it.

Inbound capital to China from the U.S.? It rocketed to an all-time high of $126 billion in 2022, the most recent year for which data is available. U.S. companies have since begun bringing their China profits back to the U.S., but China seems willing to bear the loss. Access to the U.S. market? Even with higher U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports since 2018, the U.S. imported $564 billion of goods and services from China in 2022, a new record.

Technology? That is by far the most valuable asset U.S. companies have contributed. As they clamored to access the market, China often insisted that they hand over some technology as the price of entry. In a common arrangement, a U.S. entrant would be required to form a joint venture with a Chinese company. The partner would thus see the U.S. company’s proprietary software, formulas, processes, and other technology. In addition, some technology would inevitably be stolen (a problem not unique to China, as Chinese officials note). But the technology alone wasn’t enough to transform Chinese companies into competitors. They needed two other factors, both of which required time. They needed know-how—years of experience using the technology. They also needed growth. One former CEO of a U.S. company with a substantial Chinese business says that partners stole from him multiple times. “It didn’t matter,” he says. “I still beat them. When they’re at scale, though, making more units than I am and investing more in technologies, that’s called competitiveness.”

After decades of development, Chinese companies using leading-edge tech are achieving lift-off. As they do so, U.S. companies’ roles are changing. “If they need you, they will help you,” says a former U.S. CEO who oversaw multiple Chinese operations. “But the day they don’t need you, they’ll cut you off.”

China has reached a historic turning point in its journey from a poor country to a prosperous one, from a struggling economy to a superpower. “The reform-and-opening phase is over,” says a former longtime U.S. diplomat. For U.S. companies, “risks are definitely up. Profit is definitely down.”

How is your company adapting to U.S.-China tensions and other geopolitical concerns? Share your thoughts, experiences, and insights here. Fortune will honor all requests for confidentiality.

China now dominates several strategically important industries—telecom infrastructure, batteries, solar panels, and others—with more in its crosshairs. And it’s using a game plan that has been hard to beat. A key element is creating overcapacity, which has helped China become the world’s largest producer of steel, aluminum, cement, and many chemicals, as well as solar panels. By building more manufacturing capacity than the market requires, China can flood that market with products, achieving economies of scale while pushing prices down to ruinous levels for competitors—what a longtime China hand calls “global price destruction” (a characerization that Beijing contests). Chinese companies, often helped by state ownership or subsidization, have been willing to endure the short-term financial pain; in a sense, foreign firms are competing not so much with Chinese companies as with the CCP.

Government support helped Huawei achieve global telecom dominance, and the CCP shows every sign of running the same playbook in other industries. The most striking example is EVs. With more than 100 companies, China’s automotive industry could produce about 50 million light vehicles a year—more than double China’s light vehicle sales in 2023. (For comparison, global new vehicle sales in 2023 were about 86 million.) Though final data isn’t in, China likely surpassed Japan as the top car exporter in 2023. The biggest Chinese automaker, BYD, recently passed Tesla as the world’s largest EV producer. And it doesn’t hide its ambition to be the global No. 1 for all kinds of vehicles. It has announced plans for a new plant in Europe and has ordered new ships to carry its vehicles around the world.

83%of U.S. executives doing business in China are less optimistic about the business climate than they were in 2020. Source: U.S.-China Business Council

Arguably even more important is being the world’s No. 1 EV battery maker. China’s CATL dominates that industry globally. “For a long time, Japan’s Panasonic and South Korea’s LG couldn’t get registration to sell automotive batteries in China,” says a U.S. China expert who lived in the country for years. “CATL was the only real player. China used central government investment, regulatory management, product registration, investment approval, product safety—every tool in the toolbox to give advantage to domestic makers.” Now CATL, like BYD, has overtaken every other manufacturer.

It has all happened so fast. BYD was mainly a maker of small batteries (for cell phones, for example) until it invested in an auto company in 2002. By then General Motors had been in China for five years, Ford for 10, and Volkswagen for 24. Today BYD far outsells GM and Ford in China. VW has long been China’s No. 1 vehicle seller, but its sales have been declining, and in 2023, BYD overtook it, too. Ford, meanwhile, is dropping out of the contest. CEO Jim Farley told the Financial Times last year that Ford will reduce its capital in China, explaining, “If you just reinvest in a new cycle of EVs in China, there is no guarantee, or no data, that would suggest the Western companies win.”

What is a U.S. company’s best strategy in today’s China? In the near term, the answer depends on its industry and its business relationships.

The future looks bright in industries that aren’t technologically sensitive. With China still welcoming many U.S. consumer goods and services, McDonald’s recently announced plans to add thousands more restaurants. “We’re incredibly bullish on the opportunity,” CEO Chris Kempczinski tells Fortune. “There’s no reason China couldn’t be our largest market.” Like other U.S. companies, McDonald’s set up its China operation as a freestanding entity that pays dividends to the parent; McDonald’s owns 48% and state-owned China International Trust Investment Corp. owns 52%.

U.S. financial services companies have performed well in China because they achieve efficiencies by being global. Chinese finance companies, in contrast, have a poor record outside China; for example, few Westerners know of ICBC (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China) even though it’s the world’s largest bank by revenue. But last December the CCP published an article stating that the finance sector will be expected to follow Marxist principles. In practice, U.S. firms may now struggle to invest Chinese clients’ funds in U.S.-based assets. Citigroup announced in October that it is selling its mainland consumer wealth business to HSBC Bank China, while Vanguard said it will close its mainland operations.

Consulting firms face an even dicier future, as the Bain and Mintz raids underscore. Recent laws broadly regulating how companies can possess data or move it across borders are especially restrictive for consulting firms, since their business is gathering, analyzing, and communicating data.

Facing the toughest futures are companies making products that China wants to produce on its own. As an executive with decades of China experience notes, “If you are anywhere near a product that has been put under export controls by the U.S. government”—sectors include semiconductors, AI, robotics, biotech, and more—“you know the Chinese government is doing anything it can to support your Chinese replacement.” Other high-priority technologies for China include pharmaceuticals, aerospace, electronics, and renewable energy. Going against Chinese competitors in any of them will be a long, hard slog.

A few companies are special cases by virtue of their scale; still, their actions suggest they’re mulling life beyond China. Apple assembles and sells millions of iPhones in China. But as the CCP has helped Huawei become a stronger competitor, Apple has explored other options; it reportedly plans to move 25% of its iPhone manufacturing to India. Walmart imports massive quantities of merchandise from China, but it, too, has diversified its sources. Over the past five years its Chinese imports to the U.S. have dropped from 80% to 60% of the company’s total, Reuters reports, while imports from India have grown from 2% to 25% of the total.

While every short-term case is unique, the long-term trend seems to be toward China squeezing most U.S. companies until they have to leave. One CEO of a U.S. company with a significant business in China says that 10 years ago his Chinese operation generated 23% of his profit. Now it generates 15%. He predicts it will go to 5%, at which point he will have to shut it down. Some companies have decided not to put new capital into China, opting to use only the money their existing operations generate. Others are taking capital out. “Eventually, China will have less need to regulate foreign companies out of their marketplace because their domestic competitors will outperform them,” says DeWoskin. “That’s the dynamic which to me is the most basic rule of thumb about how China is evolving.”

Xi Jinping, China’s president since 2013, has helped set the new economic agenda. For now, his vision doesn’t seem to be bearing fruit. The World Bank predicts China’s economic growth will continue to slow, from 5.2% in 2023 to 4.5% this year and 4.2% in 2025. The Shanghai Stock Exchange index has been plummeting since last May. Deflation in consumer prices could spark a downward growth spiral. Xi came to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in San Francisco in November and implored U.S. CEOs to bring their capital back. But he isn’t changing direction. Instead, he’s preparing China for hard times. In a recent speech to the nation, Xi said, “On the path ahead, winds and rains are the norm.”

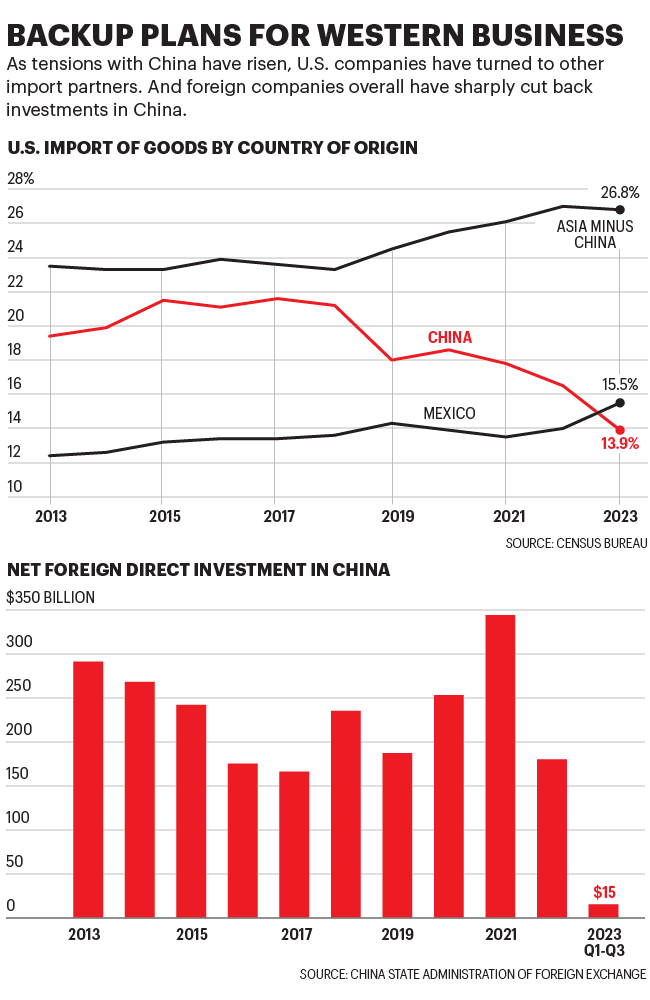

Many U.S. companies are already going “China-light” with reshoring and near-shoring. In 2023, for the first time in at least 20 years, the U.S. imported more goods from Mexico than from China. Some are finding opportunities in the largest countries of the global south—India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Brazil. A worsening geopolitical atmosphere might encourage some to speed up those efforts. As tensions rise and hostilities potentially escalate, U.S. CEOs may want to play out a scenario exercise: What if the U.S. imposed sanctions on China like those imposed on Russia after it invaded Ukraine? Those sanctions heavily restrict U.S. companies’ interactions with Russian individuals, banks, and businesses. “It’s not a far-fetched idea,” says an executive with years of China experience. “CEOs are finding they have a lot more China vulnerability than they thought.”

Nearly every American executive working today has known China only in its reform-and-opening phase. Now that it’s over, as the business climate deteriorates, CEOs face one of the hardest challenges in business and in life: discarding the old playbook and looking ahead to new risks and opportunities. “There’s a big shift with the current leadership,” says a prominent former CEO, now a director of a U.S. company with Chinese operations. “I sense that in every way. And it’s scary.”

How is your company adapting to U.S.-China tensions and other geopolitical concerns? Share your thoughts, experiences, and insights here. Fortune will honor all requests for confidentiality.

A bigger role for Capitol Hill and Uncle Sam?

Congressional Democrats and Republicans don’t agree on much, but both concur the U.S. should take a much tougher economic stance toward China—and in defense of U.S.-based companies. A new House select committee on U.S.-China competition released its first report in December. The report frames the U.S.-China business relationship as an urgent matter of national security, a term it uses some 65 times. As the report observes, “Never before has the United States faced a geopolitical adversary with which it is so economically interconnected.” It also urges the federal government to take a more active role in supporting U.S. multinationals in the economic rivalry.

Notable among its 130 recommendations:

–New controls on access of foreign adversaries including China to technologies including AI, quantum computing, biotech, optics, and space-based technologies.

–Tax breaks and other incentives for U.S. companies developing technologies with national security uses.

–Stress tests for U.S. banks to gauge their ability to withstand sudden loss of access to China.

–Tariffs on commodity semiconductors from China, to prevent it from dominating that market.

–Public disclosures of key China-related risks by large U.S. public companies.

Geoff Colvin is Fortune’s senior editor-at-large. Ram Charan is an advisor to CEOs and boards of directors worldwide. Geri Willigan also contributed to this article.

This article appears in the February/March 2024 issue of Fortune with the headline, “The China Dilemma.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance