How Canada’s COVID-19 response is faring

Over the past weeks, Canada has rolled out its fiscal measures to curb the impact of COVID-19 on Canadians, as the global economy continues to shrink. As of April 7, Canada had 17,860 cases of COVID-19, with Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia recording the most cases. Experts say the government has responded with a measured approach, providing a reasonable amount of certainty in a very uncertain time.

The federal government has plans for workers, businesses, seniors, and homeowners. The total emergency stimulus plan amounts to $202 billion. A relief program to help students is also expected this week.

Alongside these measures, the Bank of Canada cut its benchmark rate three times in March by a total 150 basis points, leaving the current rate at 0.25 per cent.

Layoffs ensued, restaurants closed, and since March 15, over three million people have applied for emergency benefits and income, government officials announced on Tuesday. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the flood of calls to Service Canada has been “historic.”

Costas Christou, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) mission chief for Canada, told Yahoo Finance Canada that the federal government has “adequate policy space to respond to the [COVID-19] crisis” because of Canada’s “relatively low levels of public debt and strong institutional framework.” He believes the government “should be prepared to do more in order to support the economy” if the situation warrants.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently launched its global policy tracker, which focuses on the COVID-19 responses taken by countries including Canada, the U.S., the U.K., Australia and China.

“The tracker gives a sense of what ministers of finance, central bankers and financial sector authorities are doing to limit the human and economic impact of COVID-19,” said IMF’s senior economist Maurico Soto.

In addition to the shock of COVID-19, IMF’s policy tracker highlights challenges oil producing countries face as they are hit by two shocks: the potential spread of COVID-19 and the sharp decline in oil prices, which has dropped below US$20 a barrel, a first in nearly two decades.

Looking to Europe, IMF says that Europe’s welfare system and social market model can support firms and households during the crisis, and like Canada, policymakers have “made good use of their policy space and institutions, putting in place large monetary and fiscal expansions to blunt the impact of the crisis.”

Germany, a country with over 100,000 cases and one of the largest number of cases of COVID-19, is offering relief such as interest-free deferrals until the end of the year, as well as access to short term work (“Kurzarbeit”) opportunities, according to the IMF’s tracker.

The COVID-19 impact

Following along in real time, Grant Thornton’s national tax leader Tara Benham says Canada seems to have taken a similar response to the U.K.

“It looks like Canada and the U.K. are focusing first and foremost on the employee, and supporting the worker,” says Benham. “Whereas the U.S. and Australia, their focus is just as large but it seems to be more about maintaining liquidity in the economy which in turn will support the employee and the workers.”

It’s a different way to do it, she says, which sees a “trickle-down effect” in the U.S. and Australia. Canada and the U.K., however, “have gone directly for a wage subsidy,” which in Canada means a 75 per cent subsidy on employees’ wages for all businesses, up from the 10 per cent figure announced in March.

The wage subsidy could take up to six weeks to be implemented. Many employers have already had to lay people off, but the hope is that with a wage subsidy, those employers could hire back staff. Employers are required to show a 30 per cent drop in revenue as a result of the pandemic in order to apply for the subsidy, which can be cumbersome to prove.

Benham says the government introduced the Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), which is intended to figure out “how we enable more Canadians to keep their jobs,” as well as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), to address, “how do we help people who’ve lost their jobs, keep food and water on the table?”

Benham believes Canada has done things the right way so far, which is to start with providing a “baseline of physiological needs [food and water] and then move forward from there.” She’s “quite impressed” with the response, and said Canada is leading by concept and filling in the holes afterwards, adding that we are getting “really broad brushes of relief that’s coming but not the details yet.”

Support Programs for Canadians

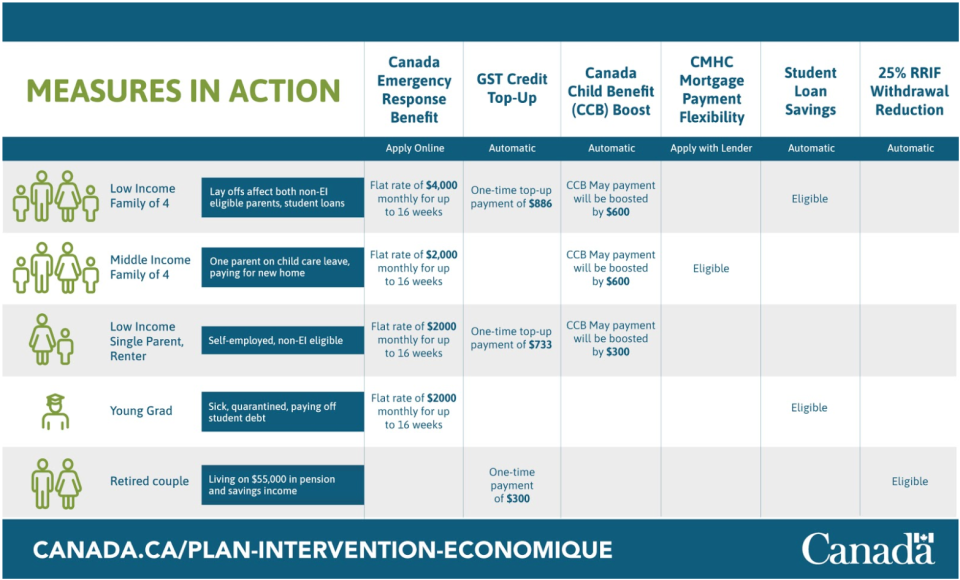

In Canada, there are now measures that will help seniors, with a 25 per cent reduced minimum for withdrawals from their registered retirement income fund (RRIF). Student loans will be placed on a six-month interest-free moratorium with no payment needed. A low-income family of four will receive a flat rate of $4,000 a month, for up to 16 weeks, and a one-time boosted GST credit is offered to eligible Canadians.

Banks are deferring some mortgage payments, and rent subsidies have been announced in provinces like British Columbia, where a freeze on rent increases and support of up to $500 a month, for up to three months, is being offered to struggling tenants.

Benham says Canada now needs to form strategies around getting customers buying from businesses again, and for the time being at least, this could be done through more online selling.

“We can’t rely on online but I think we could use it as an additional push during the next six weeks when we probably will still be in lockdown,” explains Benham.

Another area to think about changing, says Benham, is with defined benefits.

“While many Canadians are feeling the financial impact of this crisis, there are groups of individuals who are not,” says Behnam. “This includes members of defined benefit pension plans whose payments have remained unchanged to date. Those with defined contribution pension plans or private retirement savings plans, on the other hand, have seen their values decline significantly.”

“Anyone who is retiring could’ve lost that 40 per cent retirement fund or taken a hit; I know I did,” says Benham. “Everyone else has taken a hit, so I’m saying, how would others with defined benefits feel if they were asked to share? If you asked every single Canadian to step forward and participate equally, or to some extent, is that unreasonable? Probably not.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer, and other MPs said they’d donate their legislated April 1 pay raise to COVID-19-focused charities working in support of Canadians.

During this unprecedented time, Benham thinks that “we should be looking broader than just our politicians for support,” when it comes to providing aid for Canadians.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance