Can you still make money without a 'dirty' investment portfolio?

If you took fossil fuels out of your portfolio, would return potential drop? 688 institutions and 58,399 individuals across 76 countries would say no.

According to a global divestment report in December 2016 — “divestment” is the opposite of investment, where assets are sold instead of bought — institutional and individual investors have already committed to shedding their portfolios of $5 trillion worth of fossil-fuel assets.

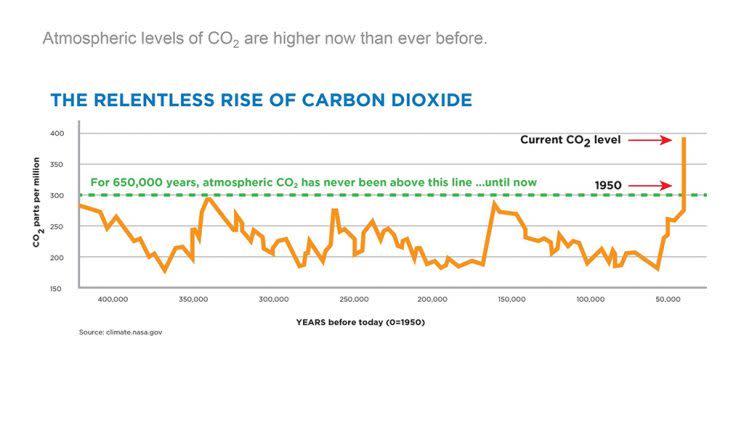

There are two main reasons people quit investing in hydrocarbons. The first is ideological. Green investors believe that by pulling their money out of fossil fuels, they can stop or at least slow down the “dirty” energy economy. According to Greenpeace, one third of all global carbon dioxide emissions come from burning coal. Because it is used to generate nearly 40 per cent of the world’s power, coal energy is currently the gravest threat to the climate.

“It’s about aligning your portfolio with your values,” says Wayne Wachell, CEO of Vancouver-based fossil-free investment fund Genus Capital. “Activist Leonardo DiCaprio divested about a year ago. If you’re talking the talk, you better walk the walk.”

The other reason is declining long-term profits. In a December 2015 meeting of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) members, 195 countries agreed to limit climate change to less than two degrees of warming. This means much of the world’s existing fossil fuel reserves cannot be tapped. Known as the Paris Agreement, this comprehensive climate pact exposed hydrocarbon investors to huge stranded asset risks.

“Reaching the goals of the Paris Agreement means most of the fossil-fuel reserves in the world will have to stay in the ground,” says Karel Mayrand, David Suzuki Foundation’s director general for Quebec and Atlantic Canada. “This is based on calculations of our carbon budget and how much more we can throw into the atmosphere before hitting the ceiling that we set for ourselves.”

It’s already happening. On Feb. 23, U.S. oil giant Exxon Mobil Corp revised down the amount of its proved crude reserves by 3.3 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The day before, ConocoPhillips revised down oil sands reserves by over a billion barrels.

“People are thinking more about the devaluation of their carbon-based assets,” Mayrand says. “There are coal companies such as Peabody Energy that lost about 90 per cent of their value in the last five years.”

Canada’s Genus Capital was one of the first to introduce a fossil-free investment division, and it currently makes up approximately 25 per cent of its $1.2 billion in assets managed.

“It wasn’t even 10 per cent three years ago,” Wachell says.

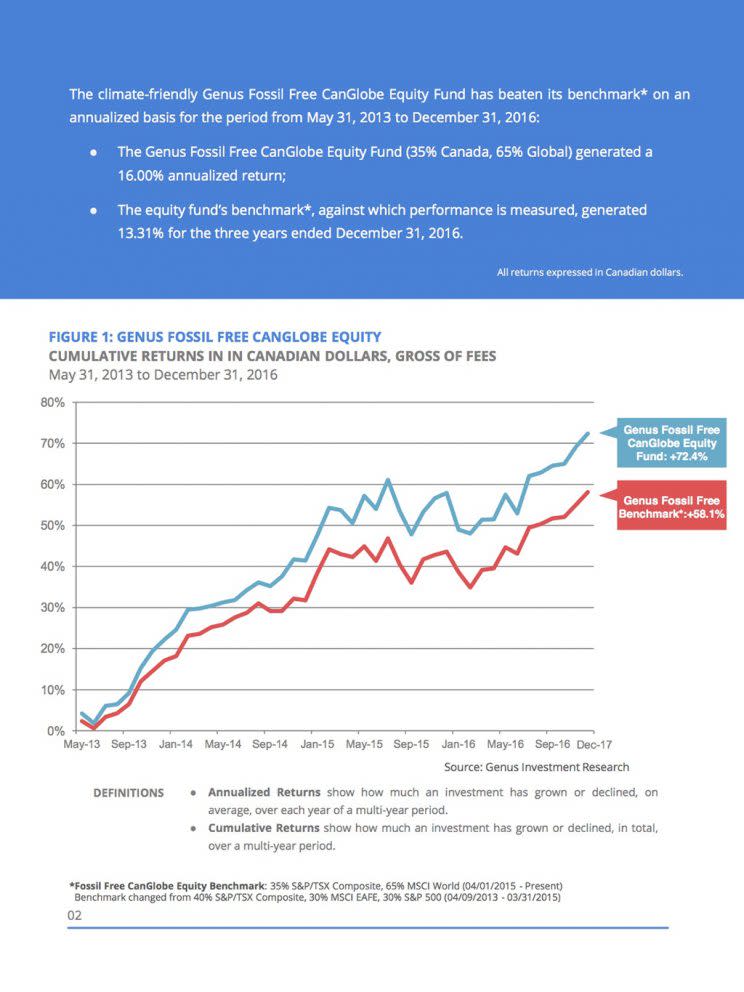

But will returns on your portfolio be lower if you divest? Not according to some fund managers. Hydrocarbons make up around eight per cent of the global market but in Canada, around 20 to 30 per cent of market share is energy stocks. Wachell believes it’s more than possible if you approach it in a smart way.

“You don’t need hydrocarbons to get performance,” Wachell explains. “But it’s a very naïve approach to just pull all the fossil fuel companies, rebalance and see what happens. We use a risk model that looks at the correlation of energy with other sectors, so we replace energy with other things that are the same sort of economic sensitivity and market behaviour. We focus on technology, financials, consumer discretionary and telecom services.”

Genus Capital saw returns on its balanced funds, Wachell says, that beat benchmarks even in 2016 when oil rose from US$30 to about US$52 a barrel. On its site, Genus shows that even if an investor had chosen to divest as early as 2000, annualized returns up till 2013 would still have been higher than the benchmark.

As demand in Canada grows, so do the investment options for fossil-fuel alternatives. Genus Capital is looking at lowering its minimum investment to $50,000. Desjardins is offering a “responsible investment” option with its SocioTerra fund, which requires an initial investment of as little as $500. NEI investments, a Canadian mutual fund of which Desjardins owns 50 per cent, offers the Ethical Balanced Portfolio with a total net asset value of $205 million. Banking giant BMO also launched its Fossil Fuel Free Fund in April 2016, which currently manages $4.66 million in total assets.

But the shift in investing is not due to a decline in coal consumption. In fact, coal consumption has decreased very little. Stock prices are based more on how coal energy will fare in the future.

“The value of fossil-fuel producing companies is based on future exploitation of their reserves,” Mayrand says. “As future projected consumption doesn’t materialize, the market corrects the difference between expected value and real consumption.”

Canadian universities are starting to divest — Laval was the first — but many institutional investment funds are not. Wachell believes it’s because policymakers need to make a stronger push for it, but aren’t because the donor class simply isn’t coming through. He says many boomers made their money in the resource sector, and to get them to adopt a new kind of strategy now is challenging.

“Our story doesn’t resonate at all in Alberta, for example,” he says.

But the time to divest is now, Mayrand warns, because later on the decision may be based on panic. Being fully divested is not something that can be done in one or two weeks, but is a process that will take several years. Despite green energy being a relatively uncertain and potentially volatile market, he emphasizes that people are going into a world that will use less fossil fuels, not more.

“Green portfolios right now are in the same situation the Internet industry was 20 years ago,” he says. “People were investing in all kinds of crazy things and some of those things turned out to be Facebook and Google and the iPhone. These new technologies became the norm.”

And what about U.S. President Donald Trump’s promises to end the war on coal? There isn’t much cause for concern, since U.S. solar energy provides more jobs than coal, oil and natural gas sectors combined.

“Most big wind and solar farms are in Republican states,” Mayrand says. “Trump can stop the wave but he can’t stop the tide from rising.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance