How what Opal Lee saw in 1939 sparked her drive for a Juneteenth holiday

We’ve relived the 1930s lately in Fort Worth, and now we realize how much Black and white Texans led separate lives.

On the big screen, we see the Masonic Home “12 Mighty Orphans,” heroes of segregation-era high school football.

On our home screens, we see the retelling of how 12-year-old Opal Flake’s south side home was burned by whites on Juneteenth 1939 to drive the family out of the neighborhood, and how that turned Opal Flake Lee into one mighty hero for civil rights and a federal Juneteenth holiday.

Last week, President Joe Biden knelt in the White House before Lee, now 94. Then he retold the story of what happened in June 1939 at the corner of East Annie Street and New York Avenue in Fort Worth.

“A white mob torched her family home,” Biden said.

“But such hate never stopped her any more than it stopped the vast majority of you.”

I’ve written before about the 1939 white race riot on East Annie Street, and about how Lee never talked publicly about it until the last few years. (She never wanted to claim victimhood.)

Now, thanks to the Star-Telegram’s digitized archives at newspapers.com, we know more about the tension before that night.

White homeowners had been arguing about whether to rent or sell to Black residents. That May, two whites on nearby East Hattie Street bickered and exchanged 12 gunshots.

Police and county prosecutors tried to settle the dispute, the Star-Telegram reported. But one official predicted “serious trouble.”

Only one white resident is named publicly as opposing having Black neighbors.

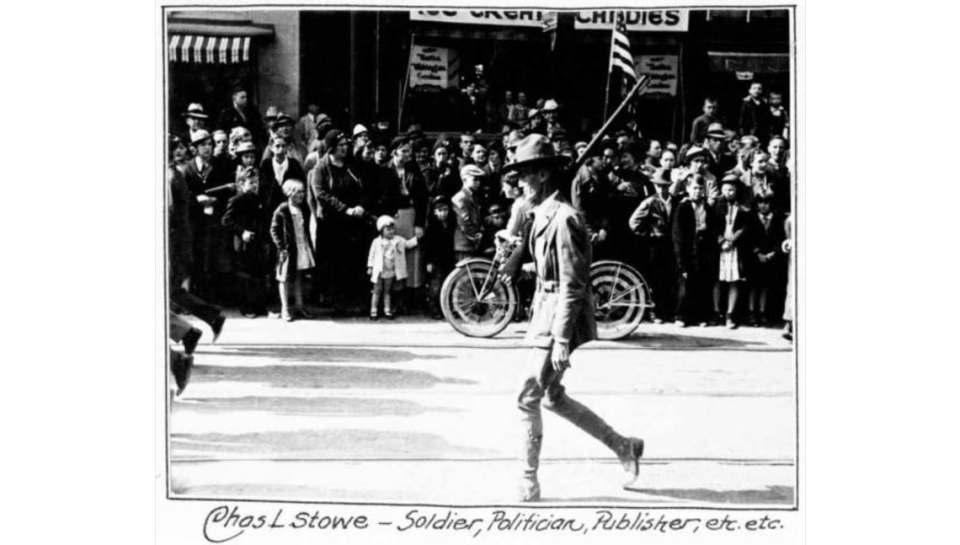

That was Charles Stowe, 65, of East Morphy Street, civic crusader, City Hall gadfly and publisher of a newsletter named “Stowe’s Chronicle.”

Stowe was a Presbyterian. But he also worked as night watchman at First Baptist Church downtown, home of Ku Klux Klan-friendly pastor J. Frank Norris.

A month before the Flakes’ home was surrounded by a mob and burned, Stowe had exchanged shots with East Hattie Street residents B.L. Manley and B.L. Manley Jr. over whether to sell and rent properties to Black residents.

Flyers had been posted in the neighborhood. They warned Black homebuyers to not move there.

The flyers were signed by the “Anglo-Saxon Committee.”

Stowe, holder of a “courtesy card” from Tarrant County Constable Dusty Rhodes approving him to carry a gun, told the Star-Telegram he didn’t post the flyers.

“I know about it but I’m not talking about it,” he said.

The president of the neighborhood association, the Rev. William Sisserson of the Fifth Ward Civic League, said neighbors were “100 percent opposed” to having Black neighbors.

But East Hattie Street resident R.H. Dean, owner of a cleaners, said he would sell property to anyone.

“[Black residents] have a right to expand like anyone else,” he said.

A month later, when the Flakes moved in, an intimidating crowd gathered for three days around their home.

On the night of Juneteenth, they forced the family out. They set the house afire as Opal and her siblings fled.

Ten Fort Worth police units were at the scene for hours along with the Texas Department of Public Safety, the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office and two county prosecutors, but no law officer took action. Police just warned Opal’s father not to shoot anyone.

“The neighbors didn’t want us,” Lee said in 2020 in one of her first retellings of the story after years of silence.

“They burned that place down.”

And sparked a fire in her heart that would change America.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance