Flea Wants to Get to the Other Side

The bass guitar never knew what hit it when Michal Balzary started playing as an aimless teenager in Los Angeles. The world would later know him as Flea, parlaying his angst into one of the most successful rock bands of the past 30 years, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and a respected film career.

It’s the angst leading up to his fame that’s chronicled in the bassist’s new, raw memoir, Acid for the Children, an exploration of an upbringing full of high highs and low lows. Flea writes about his younger years here, starting with his earliest memories of an idyllic home life that was shattered when his parents divorced, ending with the first Chili Peppers show. Along the way, he explains his instant obsession with live music (“If I grew wings and flew it wouldn’t have been any more miraculous”) and tells harrowing tales of a budding heroin addiction that almost derailed his life, with hints of the subsequent insanity—nearly nude performances and all—that would define the Chili Peppers in later years. Flea writes with gratitude of someone who is amazed he survived everything thrown his way and with a deep thoughtfulness for someone who explains he’s “often felt misunderstood by people who don’t know me and assume that I’m just a raving lunatic or shirtless dumbo jumping around slapping a bass.”

GQ spoke to the famed bassist about the book, and the life that he writes has been “a search for my highest self and a journey to the depths of my spirit.”

GQ: This book is about the period of your life before the earliest Chili Peppers show, back when the band was known as Tony Flow and the Miraculously Majestic Masters of Mayhem. Was it always the plan to focus on this specific portion of your life?

Flea: Originally I just wanted to write about the band, my relationship with it, how it affected me and my growth as a person. I thought it would have been arrogant for me to write about anything else. I thought: Everyone has an interesting life, so why should I write about mine? But once I sat down and put pen to paper, I started writing about my childhood and feeling all of these feelings. They were lodged inside and running me, without me knowing or really understanding them. It became fascinating for me. It was also a reaction to “rockstar books,” which I didn’t really want to do. In terms of the style of the book, it’s laid out like short stories: I’ve always loved short stories and the great writers, like Chekhov. So I decided to write these little stories in order to form a bigger narrative.

How do you think the music industry has changed since the period you write about?

These days it’s completely different from when I decided that I was going to be a musician and play in a band with my friends. Now they say, “We’ll get you an image consultant and set you up with social media and a publicist and a haircut and an outfit.” Back then, it was you choosing to be an outcast and a weirdo in your life. It was a ludicrous proposition to do that, even though rock music was really popular. But it was like being in junior high school and being 5’8” and saying you wanted to play in the NBA. You might be the luckiest person on earth and actually make it, but don’t fool yourself. I just didn’t care. For me, the excitement and power of music was so inspiring that it was never a question. It was just what I was going to do.

One of the more dramatic themes in Acid for the Children is your relationship with your stepfather, Walter. He was a talented jazz guitarist, but he struggled to make ends meet, and he was a very angry alcoholic. But you still wanted to pursue music: Why didn’t his fraught life and personality deter you from pursuing a musician’s life?

Well, the flip side for me wasn’t so much his lack of success as a musician; it was that he was a scary guy. He was a drug addict, and he was prone to these really terrifying episodes which traumatized and scared me, my sister and my mom. But he was a fantastic, incredible musician and watching him play just inspired me. In terms of his relationship with the music industry... there was none. He was such a dysfunctional person and played a style of music, bebop jazz, that was so marginalized at this point that there really wasn’t a place for him.

Early on, you were captivated by the power of music; you write about vivid memories of your initial musical forays and discoveries, even when you were very young. Do you think passions are learned or something akin to having a genetic trait?

I know that I was always fascinated by music. When I first heard it, I just didn’t understand how it happened or how it could be done. It was this unsolved mystery that really grabbed me. The first time I saw Walter and his friends playing hardcore be-bop jazz in our living room, it literally shook my world. The music threw me on the floor; it was like someone speaking in tongues at a church meeting or being in an ecstatic trance. It was as if it was a magic trick or Moses parting the ocean. If I grew wings and flew it wouldn’t have been any more miraculous than what those guys were doing. My yearning and my curiosity being piqued to such an extent that it absorbed me.

The first time you met Anthony Kiedis, right off the bat you were inseparable. Did you know right away that he was going to have an impact on your life when you met him?

It is really rare and I’ve been lucky to feel that a number of times in my life—to meet people and say, “This is my lifelong friend” or “This is a person that one way or another, I’m going to be connected to for the rest of my life.” There’s your family you have that are close to you and no matter what, they’re connected to you. But particularly for me, growing up in a household that was very unstable and oftentimes scary—where I just wanted to go out into the street and run away—I found a real sense of family amongst my friends. I met Anthony when I was 15, and our relationship has not always been easy. It’s been antagonistic and we battle like brothers would do—though I don’t know because I’ve never had a brother. We fight, we argue, we hurt each other’s feelings, and we’re different people. But the meaningfulness of the connection was in some ways more profound than those that I felt with my family, and obviously it’s why we’ve been hanging out hard for over 40 years now.

It sounds like you and Anthony have some of the same dynamics of other bandmates who have been together for decades and decades. There’s a lot of love there, but there’s also that mix of fame, money, drugs and creativity that tends to complicate things.

I don’t know how the relationship is between the Rolling Stones or Aerosmith—you never know what’s really there, because only they know. But clearly there’s been a lot of antagonism. Maybe that’s just par for the course in any long term relationship. But particularly when you’re in a creative relationship, you’re always making yourself vulnerable especially when thinking about something artistic, Someone will say “No, I don’t like it” and your feelings get hurt. It manifests in your life in all of these different ways. But if you’re both the same and you’re bringing the same thing creatively or the same way you saw the world, you wouldn’t have a powerful creative relationship, because you’d both be bringing the same things and it wouldn’t have that meaning. Each person has to bring something completely different. That can be difficult to deal with, but from my experience that’s where the good comes from. What’s the point of having someone there who’s going to do the same shit as you?

In the book, you write with honest objectiveness about negative moments in your life. I’m thinking in particular of an experience at a movie premiere 30 years ago, when you embarrassed someone. What was it like revisiting your wild days with the wisdom of hindsight and age?

It’s one of the reasons why I only wrote about my childhood and decided to end it where it did. While I fully consider myself an adult, even though I embrace and still nurture my childlike spirit, I felt like I could have some degree of objectivity about my childhood and understand what happened and what was going on. Part of that was having to come to terms with parts of myself that I don’t like. Part of writing—and it’s scary and difficult to confront—is dealing with the parts of myself that I’m not proud of.

That particular story you mention was something I needed to deal with, which happened at the premiere of this movie Suburbia I was in. There was a tense scene with an actor, and I was drunk with my friend and yelled out things during the film that were insulting, and I hurt his feelings. He was there with his mother and family during what was supposed to be a big night for him. I felt like such an asshole about it and I’ve always wanted to apologize to this guy. At one point I said, “I just have to find him and apologize to him.” So I'm looking him up and find him and I discovered that he was dead. He killed himself. Such is life, man. It’s heavy.

You did include a letter to him in the book. In that sense, was writing Acid for the Children cathartic?

It was cathartic in that I learned about myself. My greatest hope in expressing my feelings of loneliness and sadness in my life is that I’m able to learn and grow and evolve as a human being, and turn all that pain into art. No one is perfect, and we all have these feelings to varying degrees in different areas and in different ways. But maybe it could help other people who feel pain to feel less alone in the world. So it’s cathartic for me in that way. Coming to terms with things like forgiving people who hurt me and forgiving myself for my missteps—that is always an evolution in my life.

There are also moments in the book where you essentially scold your younger self. For example, you write about shooting heroin with the same dirty needle passed around at a party at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

All of these things I wrote about are all things that were swimming around in my consciousness. I wanted to look at them and try to understand them. Like in the instance of doing drugs in the stupidest way possible, I just feel so grateful—and watched over—that I was able to survive that stuff. And though it’s been 27 years since I’ve done drugs like that, it hurt me. It slowed down the process of learning about myself and learning to be a functional, loving light in the world, which is all I ever wanted. But, I was wild and I was in the street and didn’t know better and I made big mistakes. I was always yearning for a feeling of connection and love, but I didn’t know how to go about it. When it came time for me to stop doing drugs and drinking alcohol, I just felt everything that hurt. And from that pain, I learned. I want to walk through it, I want to grow, I want to get to the other side and be the best person I can be and I never want to stop being better.

In the book, you call fighting “an ill-conceived attempt to prove manhood” and you refer to the power of saying sorry, noting that if being punk means never having to say you’re sorry, then you’re not punk. Despite your wild days, it seems there was this level-headed kid inside you. Would it be fair to say that you were a victim of your circumstances?

I do recognize and I think it’s inherent in me that I always have cared and I always wanted to connect and build loving connections, but I was also confused and didn’t know how to articulate that in the world or deal with the pain and the hurt I felt. There were times that people gave me very enlightened messages, but I wasn’t ready to hear it yet. You have to be in a place to be ready to learn a lesson and to be able to hear, process and internalize them. Even if you know it’s right, you might be so caught up in the moment of what you’re doing that you don’t see it till afterwards. While I always consider myself a loving person, I didn’t know how to express it. Sometimes I thought I was doing things that were funny or stirring the pot and being crazy and shock value and all that, when I was really just being an obnoxious asshole. But as time has gone by, I’ve grown up. A lot of this book is really about my search for my moral compass, this thing inside of me that was really good and caring and strong, but I had to trust that enough for it to be my guiding force.

Throughout all of your drug use, you say that your most powerful psychedelic experience came from a meditation technique called Vipassana. What made it so powerful?

It’s a Buddhist meditation where you observe yourself through the images you see in your head, the sounds that you hear, like your inner dialogue, and your body sensations you have. There’s nothing else. You observe these things in the most objective and unattached way, watching them come and go for 10 hours a day along with a vow of silence and you go all different kinds of places. Eventually, you go deeper and deeper into yourself, and the deepest place in yourself is connected to God, nature and everything around you and every person. It’s so profound. When I had that feeling, it might have lasted five hours or three seconds, I don’t know. But it was a timeless, gone feeling. It was the most fulfilling, peaceful feeling I’ve ever had in my life.

You’re obviously well-read, intelligent and thoughtful. Did you ever feel underestimated just by virtue of being in a rock band known for irreverence?

On occasion. I do feel respected as a musician, and I feel like people appreciate my playing and my artistic contribution to music. There’s the thing with the Chili Peppers: We put socks on our dicks, and we’re never going to outrun it. People are always going to think of that. I feel that ultimately the measure of art that we or I created, as good as it is, over time will stand for what it is. The core essence of it, the cerebral part of it—the emotional, spiritual, and physical—are things that will always survive. But yeah, I’ve often felt misunderstood by people who don’t know me and assume that I’m just a raving lunatic or shirtless dumbo jumping around slapping a bass. But all I can do is be the best artist I can be, the best person I can be, the kindest person I can be. And do my best to uplift. That’s all I can do.

This interview was edited and condensed.

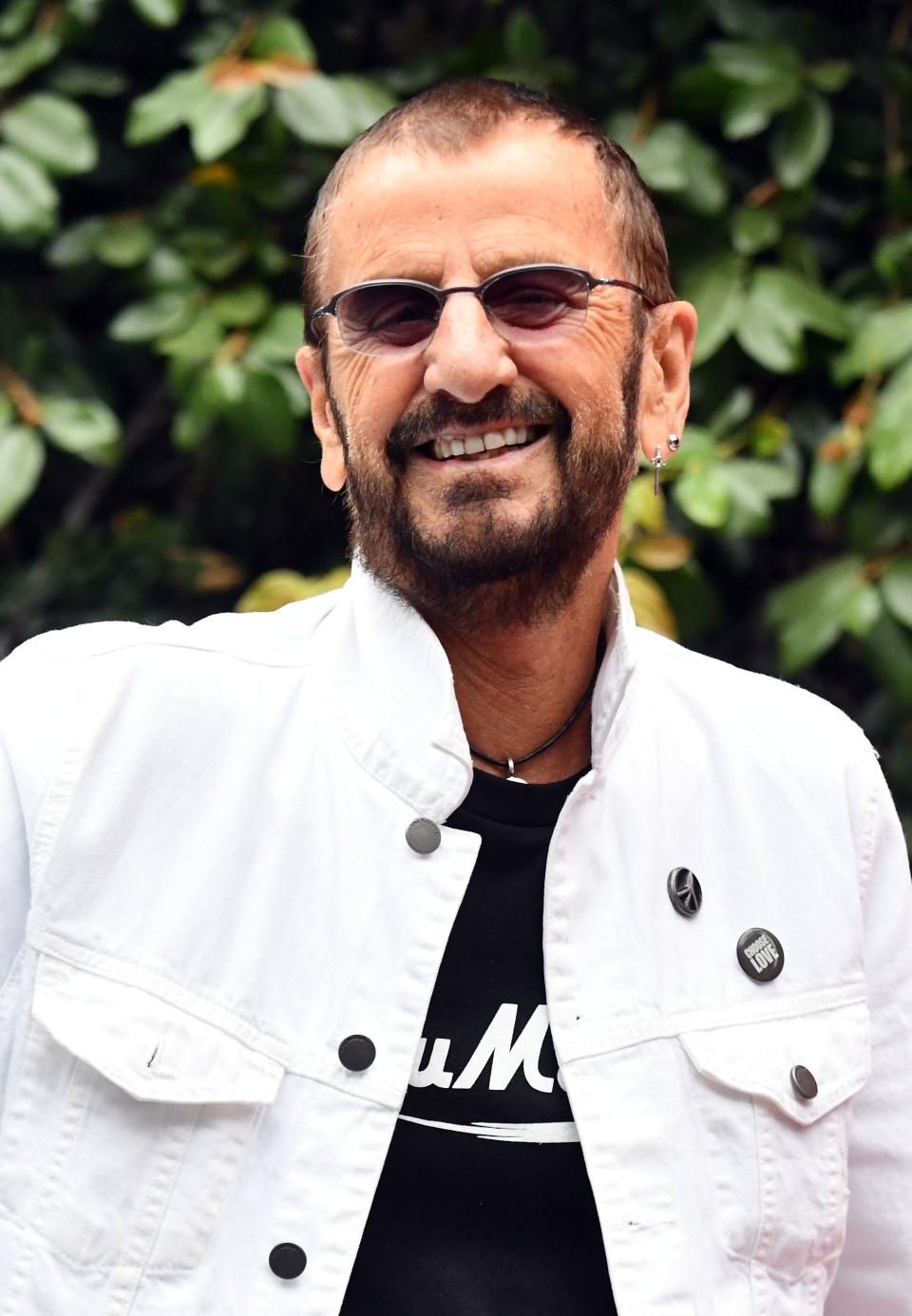

One of the most famous drummers in history tells GQ about his new album, What's My Name.

Icon

He’s as famous and accomplished as a man can be. He could just stay home, relax, and count his money. But Paul McCartney is as driven as ever. Which is why he’s still making music and why he has loads of great stories you’ve never heard—about the sex life of the Beatles, how he talked John Lennon out of drilling holes in his head (really), and what actually happened when he worked with Kanye.

Originally Appeared on GQ

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance