Why a UNC professor is on a quest to remove the ‘trip’ from psychedelic drugs

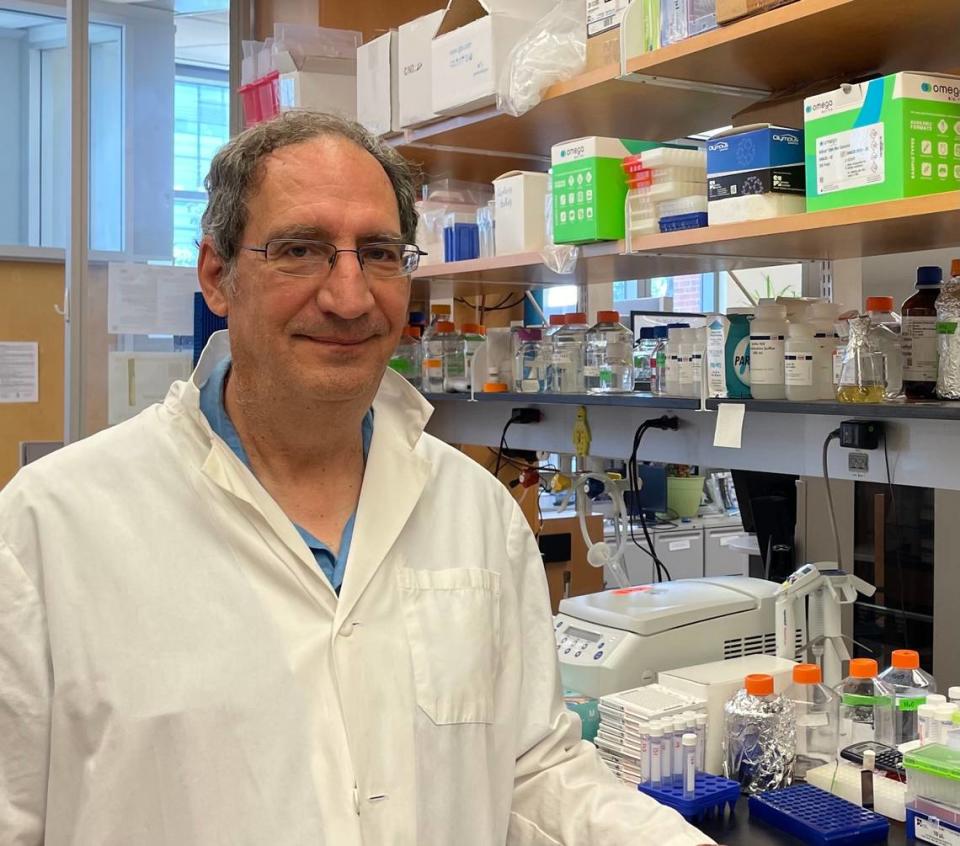

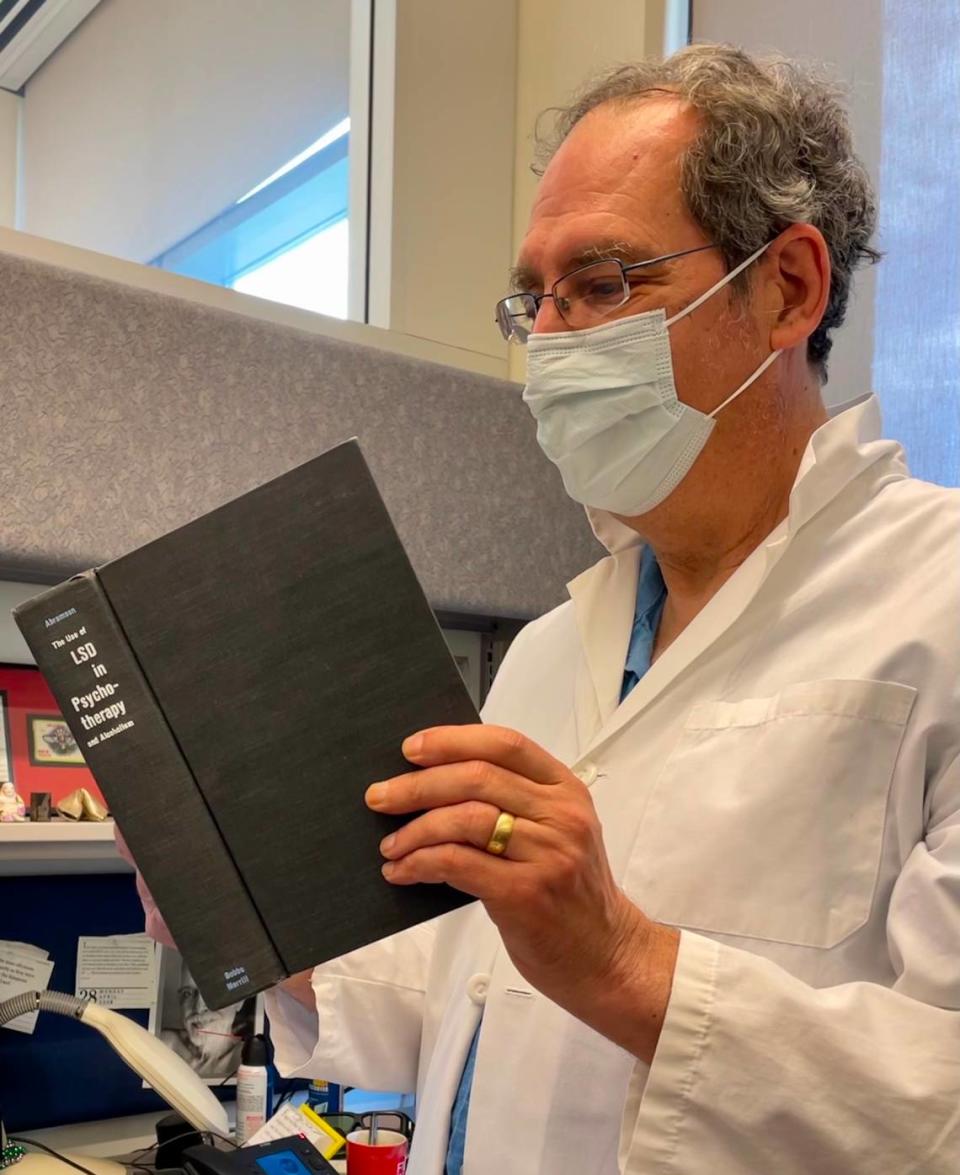

Dr. Bryan Roth’s office on the fourth floor of UNC’s Genetic Medicine Building looks like a shrine to the psychedelic era and the perception-distorting drugs that defined it: psilocybin and LSD.

On the wall above his desk, there’s a framed ticket from a Grateful Dead concert. On the other side of the room, there’s blotter paper signed by the 1960s counterculture icon Ken Kesey. Lined up on the bookshelf are copies of half-century-old academic literature on LSD.

But if Roth — one of the world’s preeminent researchers of psychedelic drugs — has his way, psychedelics could change forever.

From his two-story lab in Chapel Hill, experiments are underway to remove the powerful hallucinogenic effects from psychedelic drugs. The effort could be worth billions of dollars, and everyone from the Department of Defense to venture capitalists are monitoring his work.

Is it an oxymoron — a psychedelic drug without the trip? “Basically,” Roth said in an interview with The News & Observer.

But the fact that this research is even happening is a sign of the changing thinking around psychedelics, which are still illegal throughout most of the U.S. but are increasingly being recognized as promising therapeutics.

From recreational to therapeutic

For the past decade, privately funded clinical research has repeatedly shown the value of psychedelics to treat depression, anxiety and substance use disorders. MDMA, or ecstasy, was found to be effective in treating post-traumatic stress disorder. And in 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first ketamine-based antidepressant.

There’s also been momentum behind the use of psilocybin. In April, the first randomized controlled trial of the substance found it had similar amounts of relief as the most common antidepressants on the market.

Roth, who is a trained psychiatrist and pharmacologist, told Double Blind Magazine that from the data he’s seen psilocybin has “the most robust antidepressant effect I’ve ever seen, particularly when you consider it’s a single dose and that it appears to be long lasting.”

But those drugs will never see mainstream use, if they come with hours-long hallucinatory trips, Roth told The N&O. “Most of my patients would not want to take a psychedelic trip,” he said. “It can be frightening for people.”

And the treatments require intensive psychotherapy, with sessions sometimes lasting all day. “It’s not just, ‘Here’s a bag of magic mushrooms, call me in the morning,’” Roth said.

Yet if psychedelics were to even take a small fraction of the mental health treatment market, they could be worth billions of dollars. In 2019, more than $225 billion was spent in the U.S. on mental health treatments and services, a number that is growing quickly, according to a report from the market research firm Open Minds.

Roth, for his part, has been instrumental in revealing the science of how these psychedelic drugs actually work.

Last year, he helped publish in the scientific journal Cell the structure of how LSD binds to serotonin receptors within the brain. It was the first time anybody had shown this, and Roth said it is crucial to scientists finally getting a grasp on why the drugs can have hallucinogenic and therapeutic effects.

“There’s one receptor in the brain that psychedelics bind to,” he said, referring to the serotonin 5-HT-2A receptor. “What we’re trying to find is drugs that bind to that receptor (and) activate it, but don’t cause a psychedelic experience and are anti-depressant.”

“There are plenty of psychedelics out there,” he added. “We don’t need any more psychedelics.”

Creating new drugs

That idea prompted a $27 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a secretive research organization within the U.S. military. DARPA funds what it calls “high-risk, high-reward” research — the kind that will likely fail but could provide outsized benefits.

The organization can claim partial credit for a host of technological breakthroughs, such as the internet, GPS, weather satellites and, most recently, Moderna’s mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

“They want to transform the treatment of depression, with a pill, basically,” Roth said of DARPA. And with the money, Roth says he has brought together a “dream team” of scientists to work on the project, including ones from Stanford and Duke universities.

The initial research is happening on computers that can crunch enormous amounts of calculations. The computer program, called Ultra Large-Scale-Docking, is able to generate a billion theoretical psychedelic compounds, all of which score differently in how they activate the 5-HT-2A receptor.

The compounds don’t exist in the physical world yet. But Roth’s team plans to make the ones the computer identifies as being the likeliest to activate the serotonin receptor without triggering hallucinations.

That’s all in theory, though. It requires testing to determine if any of those compounds can achieve that — let alone have a therapeutic benefit.

“We may fail,” Roth acknowledges, noting it might be impossible to separate the therapy from the trip. But that’s all part of the game for DARPA. It could be transformational medicine, or Roth and his team may just have created new psychedelics.

Military population’s mental toil

Dr. Tristan McClure-Begley, a program manager at DARPA, said the military was interested in funding Roth’s research because there aren’t enough treatment options for depression, anxiety and substance abuse. The military, he said, is especially in need of it.

“Acute psychiatric conditions actually account for a huge proportion of medical evacuations for active duty military personnel,” McClure-Begley said in a telephone interview. He said the active duty and veteran population is more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety, and soldiers often turn to alcohol and other substances to cope with trauma. Suicide rates among soldiers also hit a six-year high last year, USA Today reported.

And selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors — SSRIs — which are the most commonly used antidepressants and include medications like Prozac and Zoloft, are not effective for everybody, McClure-Begley said.

“The indication is that the military medical operations could really use more options for treating more individuals,” he said.

And it’s not just the military that is interested.

Psychedelics are having a moment, Roth notes. Money is flooding into the research, especially from private equity firms, and multiple companies making psychedelic therapies, like Atai Life Sciences and MindMed, have gone public with high valuations.

Roth said he has met with venture capital investors who have learned about his work, and he knows it could be a big money maker.

“We have patents on some compounds, so we might license the patents out,” Roth said. “That’s something we’re looking at right now.”

The DARPA contract is expected to last for four years, depending on the success of the experiments. Roth said his team already has identified psychedelic compounds that shouldn’t trigger hallucinations, and expects to publish several papers in the coming months.

“We’ll be able to make compounds that are not psychedelic — we already have them,” Roth said, noting the compounds have been tested on mice. “Whether they’re therapeutic or not, I don’t know.”

But, eventually, Roth will know whether the effort did work.

“If we succeed, it would be huge (and) huge for UNC,” Roth said. “They could build a building.”

This story was produced with financial support from a coalition of partners led by Innovate Raleigh as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work. Learn more; go to bit.ly/newsinnovate.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance