The Unbearable Weight of Diet Culture

Throughout 2021, Good Housekeeping will be exploring how we think about weight, the way we eat, and how we try to control or change our bodies in our quest to be happier and healthier. While GH also publishes weight loss content and endeavors to do so in a responsible, science-backed way, we think it’s important to present a broad perspective that allows for a fuller understanding of the complex thinking about health and body weight. Our goal here is not to tell you how to think, eat, or live — nor is to to pass judgment on how you choose to nourish your body — but rather to start a conversation about diet culture, its impact, and how we might challenge the messages we are given about what makes us attractive, successful, and healthy.

The dawn of a new year is when many scramble to make resolutions, and in the U.S., these are often earnest pledges to shrink, tone, chisel or otherwise alter our bodies. Like years before, in the first weeks of 2021, new signups for virtual workout subscriptions and searches for “diet” on Google are spiking, because after all, every January we’re flooded with urgent broadcasts from every societal megaphone reminding us that it’s time to detox our poor, puffy bodies of the bad food choices we made over the holidays—

Wait. Stop. Just there.

“...detox our bodies of the bad food choices we made...”

This language — and the entire concept — implies that our bodies have been poisoned by peppermint bark, cookies, latkes, and eggnog, and that an antidote must be administered urgently, or else. It assumes that certain foods are “bad” and what’s more, we are bad for eating them, when in reality, this moralization of food and our collective desire to “fix” any perceived wrongdoings is a prime example of diet culture and just how easily it can sneak in under the radar. We can even fall into that trap here at Good Housekeeping, despite our best efforts, when we describe desserts as "sinful" or "no-guilt.” (Editor’s note: Now that the brand is becoming more aware of diet culture and its effects, we are actively looking for ways to be more careful with our language choices.)

“There's a whole lexicon,” says Claire Mysko, CEO of National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA). When we say we need to “burn off” or “make up for” the cheeseboard we shared with friends; when we skip the dessert we want and ponder if even snagging a bite of our partner’s dessert is “worth it”; whenever we ascribe virtue to our food choices, giggling that it’s naughty when we choose to eat what we crave or what comforts us, or good when we opt for low-calorie, low-carb, or other foods diet culture has deemed healthy. “All of that talk is part of diet culture,” says Mysko. And it is so inextricably woven into the fabric of our culture that many people aren’t even consciously aware of the daily inundation.

So what is "diet culture"?

Diet culture has many definitions and facets but, in a nutshell, it’s a set of beliefs that worships thinness and equates it with health and moral virtue, according to anti-diet dietitian, Christy Harrison, M.P.H., R.D., C.D.N., author of Anti-Diet and host of the Food Psych podcast. And it has become our dominant culture — often in ways we don't even notice since it's the water in which we swim.

Think of diet culture as the lens through which most of us in this country view beauty, health, and our own bodies; a lens that colors your judgments and decisions about how you feel about and treat yourself. Diet culture places thinness as the pinnacle of success and beauty, and “in diet culture, there is a conferred status to people who are thinner, and it assumes that eating in a certain way will result in the right body size — the ‘correct’ body size — and good health, and that it's attainable for anybody who has the 'right' willpower, the 'right' determination,” says therapist Judith Matz, L.C.S.W., author of The Body Positivity Card Deck and Diet Survivor's Handbook.

In actual fact, there is no “right” body size, and even if there were, it’s not attainable to whomever does the “right” thing (or whatever weight loss trend may be viewed as “right” at the moment), as evidenced by the 98% failure rate of diets. This stat alone is proof of the no-win norm that we, as a society, have been groomed to abide by. In one fell swoop, diet culture sets us up to feel bad about ourselves — and judge other people, too — while also suggesting that losing weight will help us feel better.

Urging people to examine, question, and ultimately reject diet culture is at the heart of the anti-diet movement, whose prominent voices include Harrison, NEDA, a crowd of activists in the Health at Any Size movement, the body positivity movement, and many others. The anti-diet movement is, in part, working to debunk the diet culture myth that thinness equals health and raising awareness of and helping to end fat phobia and discrimination against people in larger bodies. And because a tenet of diet culture is, well, endlessly dieting to be thinner no matter the mental and physical cost, the anti-diet movement rejects diets for the purposes of weight loss.

And here’s the thing: We are all products of diet culture, so it’s understandable why roughly half of adults have been on a weight loss diet in the last year alone. Dieters are just doing what we’ve always been told is the best thing for our health and appearance, and by implication, will bring us the perceived shiny futures of the people in the “after” photos. To be clear, “the anti-diet movement [is not] anti-dieter,” says Harrison. Rather, the anti-diet movement challenges diet culture and, as result, takes issue with the many restrictive diets that are scientifically proven to have a negative impact on cognitive function, heart health, and mortality, while contributing to social injustice and weight prejudice.

Anti-diet aims to free people from spending every waking moment policing their bodies, wasting precious time and energy obsessing over food choices, calories, macros, and the like. It aims to help people fill their bellies with the food they want and need, and without the distraction of constant hunger, allow their minds to see issues that are much bigger and more important than the way we look and how we eat. It helps us realize that the secret to happiness and freedom is not, in fact, locked within a smaller body requiring a "willpower" key, as diet culture has long made us believe.

Even if you’re not consciously trying to lose weight per se, diet culture often crops up in choices we think we’re making for health, to feel or look good, fit in, or even just make conversation amongst friends over dinner (“oh, I know, I feel this cake making my hips bigger as I eat it,” or, “ugh, we need to go to the gym after this”). But subconsciously, diet culture “creates this idea — and reinforces it at every turn — that you have to be thin in order to be successful, accepted, loved, healthy: All of these things that we want for ourselves that are just understandable human desire,” says Harrison. “It tells us that weight loss is the secret to that. It tells us that weight loss is a way to attain those things.” And it's a house of cards, because it's not.

What are some more examples of diet culture?

Diet culture can be found in Barbie’s thigh gap and 18-inch waist, which influences perceptions of what an “ideal” body should look like. It’s Lululemon’s founder saying publicly that it's a problem when women's thighs touch. It’s Kim Kardashian explaining how “necessary” it is to squeeze into shapewear beneath a dress, saying, “without shapewear, you’d see cellulite and I just wouldn’t feel as confident.” (Also, that her shapewear brand, SKIMS, allegedly sold $2 million of product in minutes when it launched.) It’s the fact that you may have been told (or recited!) that at the first sign of hunger, instead of giving your body the food it’s asking for, you should delay and drink a glass of no-calorie water first in case you’re “actually just thirsty.” Even Good Housekeeping's own article on 1,200-calorie diets is a tricky juxtaposition: The article aims to serve the approximately 40,500 people who search for 1,200-calorie meal plans on Google every month despite a 2015 study that shows this number of calories falls within the realm of clinical starvation. Although GH strives to provide safe, nutritionist-backed advice, we also realize how this can contribute to the bigger problem.

As anyone who’s ever looked into the mirror and wished for a flatter this or a bigger that can likely attest, there’s an unattainable and rigidly narrow Western, white beauty ideal to which many of us often compare ourselves, and to which many of us are held by other people. “Nobody ever wakes up in the morning and says, ‘Gosh, I look terrific. I feel so healthy, I'm so attractive: I think I'll go on a diet,’” Matz points out. “It always starts with negative thoughts.”

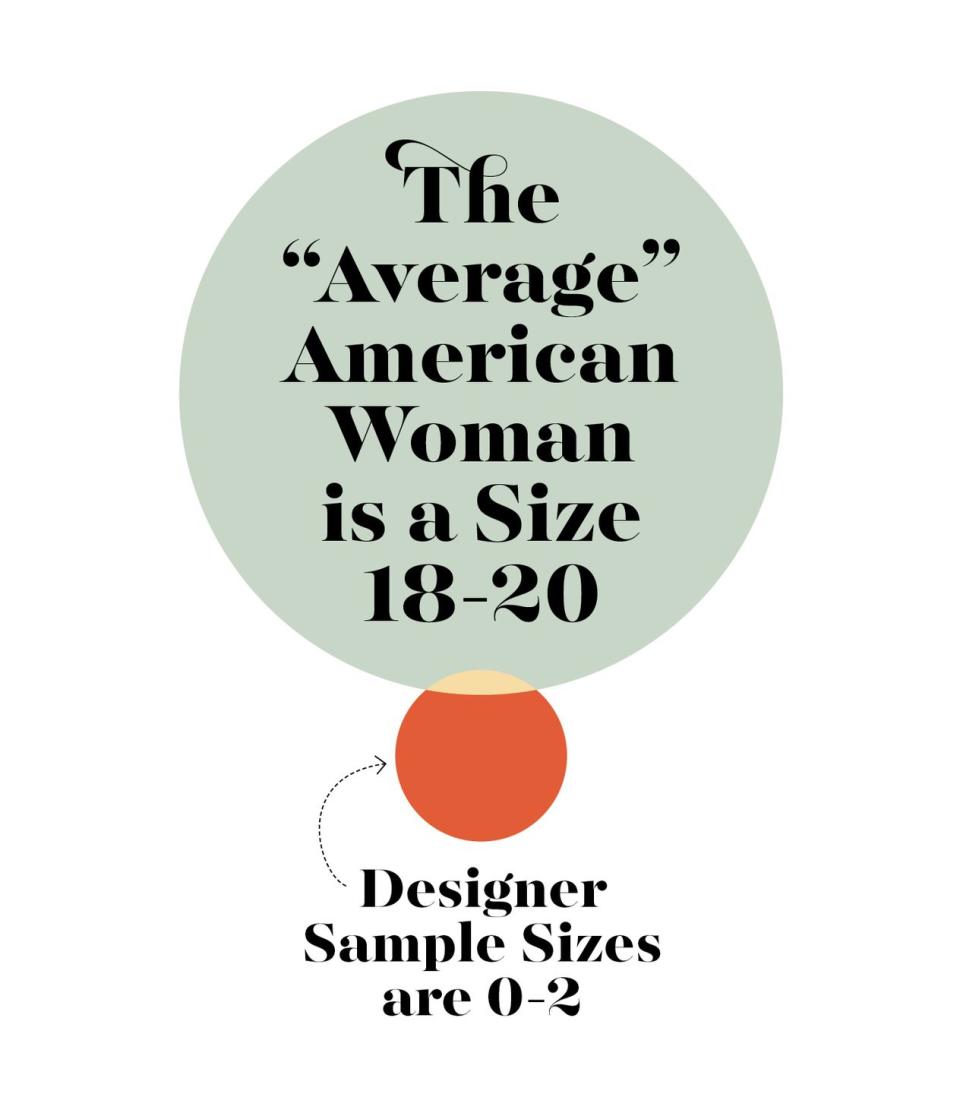

Instagram influencer culture, movies, runways, fashion ads, and media outlets including magazines are rife with one type of person: A normatively feminine, usually white woman who is slim and tall and seemingly living fabulously. Could their charmed lives be because of those “perfect” bodies? The sample size for many designers is 0-2, while a 2018 study by National Health Statistics Reports published by the CDC places the average American adult woman in a size 18-20, and teen girls in a size 12.

While what is truly “average” varies greatly on genetics, family history, race, ethnicity, age, and much more, size and weight are actually not good indicators of health in the first place — you can be smaller-bodied and unhealthy, or larger-bodied and fit. Even so, “we're exposed to the steady stream of images and messages that reinforce diet culture and reinforce the idea that to be happy and successful and well-liked … you have to look a certain way, have a certain body, and follow a certain fitness or meal plan or diet,” says Mysko, which keeps people unhappy in their bodies, chasing something they can't ever catch, and spending loads of money to do so.

Why is diet culture harmful?

Anti-diet advocates argue that diet culture harms everyone with a body, particularly (but certainly not limited to) people who are in larger bodies. Though healthy bodies come at every size and shape, our societal experiences vary greatly depending on a given person’s size — weight stigma and thin privilege are both very real — and no one is safe from feeling othered by diet culture. Even those in "average" or slender bodies can feel that they're not thin enough in the exact right places. This all “leads to people feeling a lot of shame about their body and feeling that being thinner is worth pursuing at all costs,” says Matz.

The result: “People choose from hundreds, if not thousands, of diet plans or restrictive food plans.” In November 2020, the CDC reported that more people are actually dieting now compared to 10 years ago. Part of the problem is that the term “wellness” is often now used as a euphemism for “diet.” But understanding diet culture and how it impacts us isn’t only about how any given individual responds to it: It’s about recognizing that diet culture is baked directly into American culture and is intrinsically linked with racism and patriarchy. “What constitutes ‘good’ behavior is going to be far more accessible to white persons, to men, to wealthy persons, than people who do not fit into those categories,” says Sabrina Strings, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology at the University of California at Irvine and the author of Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. This includes conventional thinness.

“When you have been told that you should only have [a certain number of] calories or that you must keep your BMI here, you will always feel like you are doing either good or bad, right or wrong by sticking to these dictates,” Strings adds. “Unfortunately, there are a lot of myths, [including the concept that] if you just restrict your food, then you'll be able to attain that weight,” says Matz. What’s more, says Strings, “Whenever we create standards about how we all should live, these norms always benefit those individuals who are already in power.” Here are some key issues with diet culture:

It promotes discrimination. Whether it's Bill Maher pleading for fat shaming to "make a comeback"or kids being teased in school because of their weight, the mocking and bullying of people because they're fat is a part of diet culture that is both common and harmful. But beyond that, weight-based discrimination actually impacts access to jobs, healthcare, and more. In 2012, a metastudy found that fat people are regularly discriminated against in "employment settings, healthcare facilities, and educational institutions," making it difficult for people in larger bodies to live functionally or fruitfully in our society.

And according to a 2010 study, “stigma and discrimination toward obese persons are pervasive” which threatens their psychological and physical health, creates health disparities, and contributes to a looming social injustice issue that goes widely ignored. Then, in an attempt to gain equal access, fat people are led to diets that further harm them physically and mentally: Consider that one study showed the calorie intake for many popular diets is "comparable to that of the most undernourished global regions, where severe hunger interferes with individuals’ ability to thrive and make meaningful contributions to society.”It fuels a business designed to take your money. Americans spend billions of dollars annually trying to attain what diet culture promises, almost always to no avail. According to Market Research, the total U.S. weight loss market grew at an estimated 4.1% in 2018 to $72.7 billion and is forecasted to grow 2.6% annually through 2023. “With that kind of money, with that kind of industry at stake, it's really hard to get that to go away — even with a growing and powerful movement like anti-diet,” says Harrison.

It’s a setup for feeling like a failure. Scientifically speaking, weight loss diets don’t work. “There is zero research out there that shows any weight loss plan or product helps people achieve weight loss [and maintain it] over a two to five year period,” says Matz. “If there was something that was sustainable for the majority of people, we would all know about it.” (There isn’t, so we don’t: Instead, we get a new diet every month that fades away when the next glittery “fix” comes along.) Even doctors often prescribe weight loss as a cure to many medical maladies despite the fact that dieting is biologically set up to fail. “Up to 98% of people, according to research, regain all the weight that they lost within five years, and up to two-thirds of people end up regaining more weight than they lost,” says Harrison, and that’s because “our bodies are really designed to protect us against famine.”

Matz agrees: “Our weight regulation system is beyond our conscious control.” This is evidenced by a 2010 F1000 Medicine Report that shows there is an active, biological control of body weight at a given set point in a 10-20 pound range. “The message this culture gets is that you can decide what weight you want to be with enough willpower, but it’s just not true,” says Matz. So, Harrison wonders, “Why do 100% of dieters think they're going to be in the 2%?” Perhaps the larger problem is that because of diet culture, when we do gain weight back post-diet, we have learned to internalize it as a failure of self instead of accepting that it is ultimately a success for evolution and our bodies’ way of protecting us from starvation.It distracts from a larger societal issue. Our individualistic culture says that if you’re not thin, not only is it your "problem," but it’s your fault. Being in a large body is actually not a problem, but diet culture says it is because that’s easier than investing money and energy in giving everyone access to fresh food and ample outdoor space in which to move, connect, and enjoy nature. "If you've ever visited a community that only has a convenience store as a local means of any type of nutrition, then you will know that people often don't even have fruit in their neighborhoods ... in a low income area," says Strings. These “food deserts,” as they’re called, are partially to blame for what a 2011 study found: “The most poverty-dense counties are those most prone to obesity.” The issue with this finding isn’t obesity, which isn’t an accurate indicator of health, but rather the fact that our society lacks adequate resources to foster health separate from weight across socioeconomic lines.

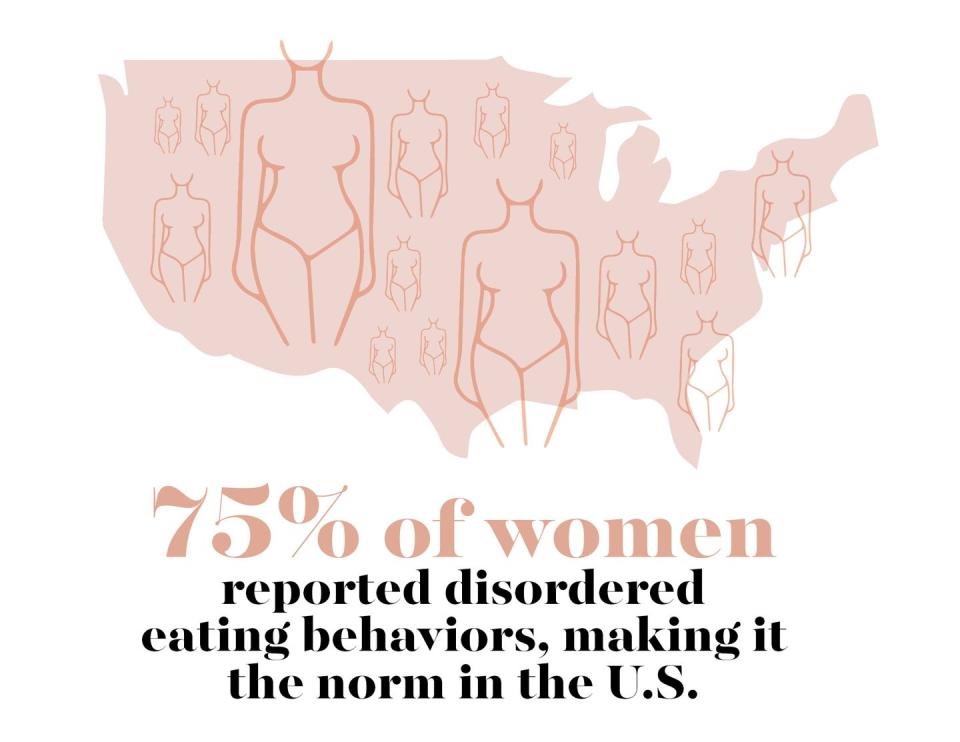

“If we lived in a society where neighborhoods were walkable and people could get access to clean drinking water and plenty of sleep, people would already be far healthier than they are now," says Strings. But, she continues, diet culture gives a permission structure for the finger to be pointed elsewhere. “Rather than focusing on these larger structural issues that could have a global impact on a population, we want to target individuals and tell them to change their bodies in ways that are unrealistic and unproductive.”It normalizes disordered eating. An eating disorder is a clinically diagnosable condition. But if you were to ask 100 people a series of questions that indicate disordered eating (per NEDA’s screening tool: How afraid are you of gaining three pounds? Do you ever feel fat? Compared to other things in your life, how important is your weight to you? Do you consume a small amount of food on a regular basis to influence your shape or weight?), it would become clear that the issue is far more pervasive than you think.

A 2008 survey sponsored by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill showed that a whopping 75% of women reported disordered eating behaviors that “cut across racial and ethnic lines,” and occurred in “women in their 30s and 40s ... at the same rate as women in their 20s.” That means disordered eating is the norm in the U.S. for women of all ages and race. It’s a staggering statistic, and one that goes under reported since a lot of these behaviors support the very underpinnings of diet culture itself.It’s self-perpetuating. Imagine if your vacuum had a 98% failure rate. You likely wouldn’t blame the ensuing mess that grew each time the vacuum didn’t start. You'd blame the machine (and you'd also presumably trade it in for a more reliable model pretty quickly). But when we diet and, later, gain the weight back, as 98% of people will, we instead berate ourselves. Dieters “do what diet culture teaches them to do by dieting,” says Matz, “but then, when it doesn't work, they blame themselves rather than the diet.” And then we restart the cycle instead of just buying a new damn vacuum.

How can I resist diet culture?

Diet culture can foster a toxic way of living for many people, but because of its pervasiveness, it can feel intimidating and deeply personal to pick it apart. Anti-diet culture aims to “dismantle this oppressive system of beliefs ... so that people have the chance and the choice to be able to be free of those stigmatizing and body shaming beliefs,” says Harrison.

Being resistant to diet culture is also not anti-health or anti-nutrition: It’s quite the opposite. With this movement, “It's absolutely possible that we can encourage and also give people the resources to eat healthy and to move their bodies in a healthy way without having to be the disciplinarians that tell people they must weigh a certain amount,” says Strings. The anti-diet movement advocates for evidence-backed measures of health that are not about body weight, and there are even anti-diet dietitians and health professionals, like Harrison, who help guide patients out of diet culture and into decisions that are healthy for body and mind — and that don’t aim to modify the body’s appearance.

Here are some aspects of anti-diet culture that can actionably put an end to the restriction and guilt cycle of diet culture:

Consider intuitive eating, an approach that was created in 1995 by registered dietitians Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch. It is based on 10 core principles — like honoring your hunger, challenging the food police, and coping with your emotions with kindness — by which you let your body guide you in what and how much to eat.

“With intuitive eating, instead of eating from the outside in, instead of following rules from a diet, people learn to use their internal physical cues to decide when, what, and how much to eat,” says Matz. By destigmatizing food choices, intuitive eating steers you back into your own body. Most people have “gotten so used to eating what they should and shouldn’t eat, what’s ‘good’ and ‘bad’, they’ve really lost touch with ‘What do I want? What would satisfy me?,’” says Matz. There are a host of professionals trained and certified in intuitive eating standards, from counselors to psychotherapists to registered dietitians, who can help guide you through the process too.

Getting reacquainted with your body’s natural hunger cues, cravings, and needs can take time, but can ultimately free you from the learned shoulds of diet culture. The irony: Most find that once you grant yourself permission to eat the things you want when you want, your "fear foods" (you know, the things you declare you “cannot have in the house or I’ll eat the whole bag!”) have less of a siren song. When the scarcity mindset drops, so does the need to overeat out of fear of never having it again. “Remember that we come into this world born knowing how to do this,” says Matz. “Babies, when they're hungry, cry. So really, we're going back to the way we were born: Eating.”

Look into the Health at Every Size (HAES), a movement that recognizes “that health outcomes are primarily driven by social, economic, and environmental factors,” not weight, to encourage the pursuit of health without a focus on weight loss.

HAES is built on pillars of weight inclusivity, health enhancement, respectful care, eating for well-being, and life-enhancing movement, all with the ultimate goal of tuning into your body’s innate guidance to make food and movement choices that help you feel confident, nourished, fulfilled, and healthy inside your body without trying to change its appearance. “It looks at people's health status, separate from weight,” says Matz, and it’s “really doing a great job of giving people information that … you can be healthy regardless of your size,” says Strings.

Strings adds that HAES is built upon the belief that you are worthy of love and respect, regardless of your size. In a society that demonizes fatness, it’s a simple but novel concept. As Strings says: “Just to love yourself and to know that you can be healthy regardless of your weight is really a revelation to probably most Americans.”

Anyone feeling like they are suffering from disordered eating or an eating disorder can and should reach out for help immediately. The NEDA helpline at (800) 931-2237 is available daily via call or text, and officials also are on standby in digital chats, ready to help you find resources in your area. If you are concerned about a loved one, learn more about how you can help.

Note: This article was originally published on January 23, 2021, and edited on January 29, 2021 to offer clarification on the anti-diet movement.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance