UK’s deep-sea mining permits could be unlawful – Greenpeace

Deep-sea mining exploration licences granted by the British government are “riddled with inaccuracies”, and could even be unlawful, according to Greenpeace and Blue Marine Foundation, a conservation charity.

The licences, granted a decade ago to UK Seabed Resources, a subsidiary of the US arms multinational Lockheed Martin, have only recently been disclosed by the company.

In March lawyers for Greenpeace wrote to Kwasi Kwarteng, secretary of state for business and energy, in March, warning of potential legal flaws in the licences. They have not received a response, they say.

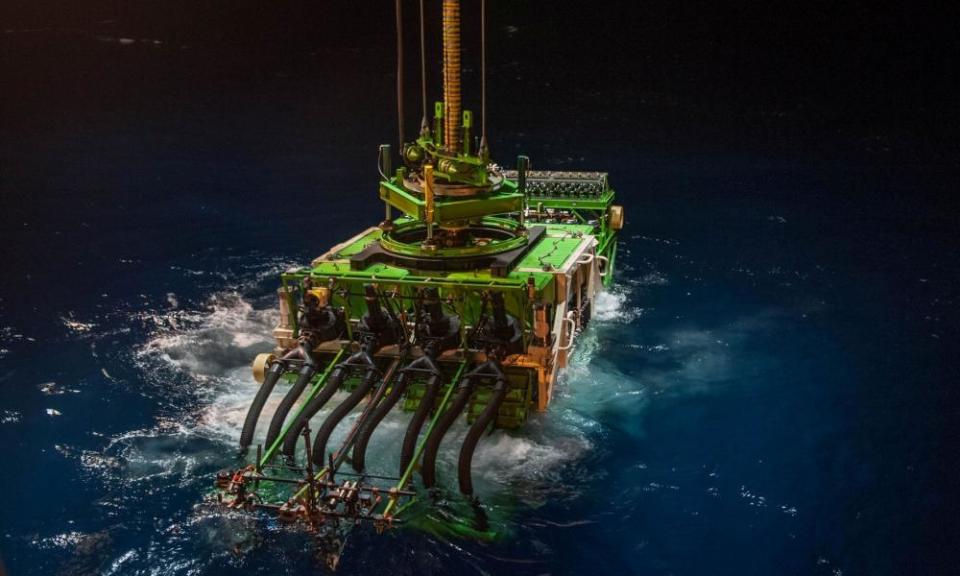

The licences, which detail the UK’s responsibilities as a sponsoring state of UK Seabed Resources (UKSR) in its exploration of polymetallic nodules on the Pacific Ocean seabed, appear to have been granted for 15 years, but UK law only permits a maximum initial period of 10 years. This suggests they may be unlawful, the campaigners say.

Flaws in the certificates include the mapping of exploration areas more than twice the size of the 133,000 sq km (51,000 sq miles) area in which UKSR is permitted to operate, as well as a failure to include a provision for an environmental-impact assessment, the groups say.

The licences also state that the UK shall sponsor UKSR for exploitation of the deep sea if the company meets the condition of the licence and successfully applies for full-scale deep-sea mining. This undermines the reassurance ministers gave MPs last year that Britain had agreed not to sponsor or support exploitation of deep-sea mining until there was sufficient scientific evidence about potential impacts, and until strong environmental standards had been developed by the International Seabed Authority and were in place, the groups point out.

Louisa Casson, of Greenpeace’s Protect the Oceans campaign, said: “These licences are riddled with so many errors and inaccuracies that their very lawfulness is thrown into question. For nearly a decade, our government has hidden these important documents from public scrutiny, and now it’s clear why: they starkly expose the gap between the government’s rhetoric and its action when it comes to protecting our oceans.”

Campaigners have been trying, unsuccessfully, to access the licences from the UK government for two years, via freedom of information requests. Lockheed Martin released the licences in March.

Charles Clover, executive director of Blue Marine Foundation, said: “If governments cannot be trusted to get the exploration phase right, what hope is there of them managing potentially environmentally catastrophic deep-sea mining responsibly? These licences show a clear lack of diligence and oversight on the part of the UK government, highlighting once again the need for a precautionary pause on all deep-sea mining.”

The move away from fossil fuels is creating an ever-increasing demand for the materials that used in making batteries, some of which are found on the seabed, where ecosystems have yet to be fully explored.

Scientists, conservationists, wildlife and ocean groups have called for a halt to any exploitation until impact on the environment is properly understood.

Two months ago, Google, BMW, Volvo and Samsung signed up to a World Wildlife Fund call for a moratorium on deep-sea mining.

A UK government spokesperson said: “The UK is playing a crucial role in ensuring that strong environmental standards are upheld in the growing deep-sea mining industry.

Related: Deep-sea ‘gold rush’: secretive plans to carve up the seabed decried

“We have agreed not to sponsor or support the issuing of any exploitation licences for deep-sea mining projects until there is sufficient scientific evidence about the potential impact on deep-sea ecosystems, and strong and enforceable environmental standards have been developed and put in place by the International Seabed Authority.”

The licences are subject to periodic review and so would not be extended beyond 10 years without one, in line with legislation, according to the government. The licences state that the UK will act as a sponsor state if certain conditions are satisfied and that the conditions would not be met without evidence related to environmental standards. Further environmental assessments would have to be carried out before any exploitation licence was issued.

A Lockheed Martin spokesman said: “The licences we currently hold were granted subject to periodic review, and would not be extended beyond the initial 10 year period without a review by the secretary of state, which is in line with relevant legislation.”

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the seabed and ocean floor is the “common heritage of mankind”. The ISA is an autonomous organisation mandated by the UN to oversee the convention. Any private company wanting to explore or exploit the resources of the seabed has to partner with a government that is a member of ISA and party to UNCLOS.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance