The spies who hated us: reporting on espionage and the secret state

It is time for morning coffee and Richard Norton-Taylor and I are discussing secrecy, deception and brown envelopes, which comes naturally to the pair of us, as past and present defence and security correspondents of the Guardian.

Norton-Taylor joined the paper in January 1973 (when, incidentally, this writer was not yet two), starting in Brussels and switching to security a few years later. The first part of his career was dominated by a series of landmark official secrecy battles.

“Brussels was great for spy-watching: Nato was there, as well as the youngish EEC,” he recalls, indicating there was no shortage of Russians in town. Returning to the UK in 1975, and armed with that experience, a job was defined for him by the Guardian’s then editor, Peter Preston, initially covering “official secrecy and Whitehall”.

At that time, the British state made what turned out to be the mistake of trying to stop leakers through the courts. “There were tremendous cases, and the government’s behaviour was so counterproductive,” he says; the scenario all reporters covering state secrecy thrive on.

Such trials are less frequent today, and often more of the action takes place in parliament, little engaged in intelligence matters 30-plus years ago. These days, I tell Norton-Taylor, it is critical to remain plugged in to the gossipy world of Westminster, from which so many stories emerge over coffee, WhatsApp and drinks.

There no shortage of high points during my predecessor’s heyday. “There was the Clive Ponting trial,” he says, referring to the sensational 1985 acquittal by a jury of the civil servant accused of breaching the Official Secrets Act by leaking documents relating to the sinking of the Argentinian cruiser General Belgrano during the Falklands war.

“But the glorious thing about that was that the day Ponting was acquitted, the Guardian went on strike. So it wasn’t until the day after that we could report on it – two whole broadsheet pages on the Belgrano case.” Was that frustrating? “Well, you have a few more drinks – it was classic Guardian.”

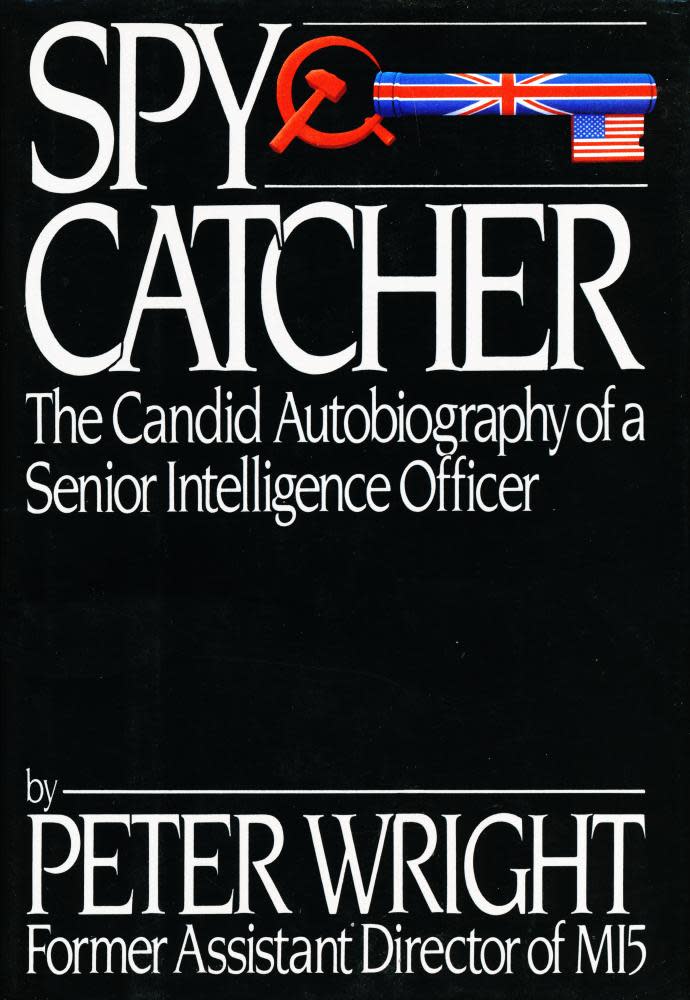

Shortly after came the Spycatcher affair – the British government’s repeated and increasingly embarrassing attempts to prevent the publication of the memoirs of the former MI5 officer Peter Wright. Norton-Taylor recalls publishing a summary of the contents of the book, which led to an injunction.

The battle then moved to Australia, where the book’s publishers hoped to release Wright’s account. So did Norton-Taylor. “The trial was in Sydney for six weeks,” he recalls, which required the Guardian’s reporter to stay in the Sheraton at a time when expense accounts may have been a little more generous.

Malcolm Turnbull, who later became Australia’s prime minister, acted for the publisher “putting the boot in to the uptight British establishment”, while Robert Armstrong, the cabinet secretary, gave evidence in which, rather than admit to lying, he used the phrase “economical with the truth”.

The British government lost, Spycatcher was published in Australia, and copies immediately made their way to the UK. “The Australian judges loved putting the boot into the Poms, I loved it, and I think the Guardian readership loved it,” Norton-Taylor says enthusiastically.

The Sarah Tisdall affair was one of the most difficult situations ever faced by the Guardian – one that strained relations between the paper and the authorities. It started with a brown envelope delivered anonymously one Friday evening in 1983, which contained the secret timing of US cruise missile deployments at Greenham Common – an extraordinary scoop.

But under huge pressure and after an adverse court ruling that raised the threat of heavy fines, the documents were returned and the leaker, Tisdall, was jailed for six months. Norton-Taylor was peripherally involved in the story, but recalls the pressures facing the editor, Preston, who said he feared that mounting fines might ultimately sink the Guardian.

The Ponting and Spycatcher episodes prompted a modest opening-up among the security establishment, and here it is possible to compare notes. Today, MI5 and MI6 have something approximating press contacts – people that correspondents can contact (although they cannot be named or, normally, quoted).

Norton-Taylor says that, back in the late 1980s, this was an innovation – with the Guardian and the Times being first provided with authorised numbers to ring. “Ken Clarke, when he was home secretary, said it would be like the dance of the seven veils: give them a little bit and they will want more and more. So, sometimes, ministers are opposed to answering more questions,” Norton-Tayor adds.

Who gains from these exchanges, though? There is a risk reporters become too dependent on their contacts and the meetings that take place on park benches where passersby cannot easily listen in. The way to deal with that is to read widely, cultivate a variety of independent sources, and step back and always be prepared to evaluate critically what you are being told. It is not a job for the credulous or unsceptical.

Norton-Taylor argues “they need us as much as we need them” – and adds: “If they say they have a good story and it turns out to be wrong or exaggerated, you will lose trust in them and they don’t want that. In a sense, it’s not that difficult.”

Nevertheless, relationships like this can easily become complex. I tell my predecessor that a spy helped on a recent story – it is not possible to say which – only to subsequently warn that, if it got out that they had helped, then not only would they deny assisting, but they would suggest I had drawn the wrong conclusions. What had been presented with conviction would suddenly become grey.

This prompts Norton-Taylor to tell an anecdote relating to the run-up to the 2003 Iraq war. An MI6 officer had told him, he says, that the reason why some MI6 people were against the invasion of Iraq was that “some of the stuff floating around about Saddam Hussein and al-Qaida being allies was ridiculous. Saddam Hussein was a secular dictator, wasn’t exactly in love with Islamic extremism.”

A particular concern was that “the Foreign Office and the British government were accepting everything the CIA and the Americans were saying” – and even some parts of MI6 were willing to go along with that, because a war in Iraq was what the US president, George Bush, and his British counterpart, Tony Blair, wanted.

Shortly after, a piece appeared in the Guardian, summarising the information contained in the conversation – only to prompt a complaint from the source a day later. A somewhat bemused Norton-Taylor recalls asking: “Was the piece accurate?” To which he was told: “Yes, it was accurate, it just shouldn’t have been in the public domain.”

That is a surprisingly common response from Britain’s security establishment, who seem surprised when reporters write up stories based on information they have gleaned. It’s a reminder, too, why it can often be best to write a story and deal with any consequences later: it pays to follow your judgment – and hold your nerve.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance