'Both of your hands can touch both walls': Former prisoner describes the psychological toll of solitary confinement

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

This is part 3 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the prison industry. Listen to the series here.

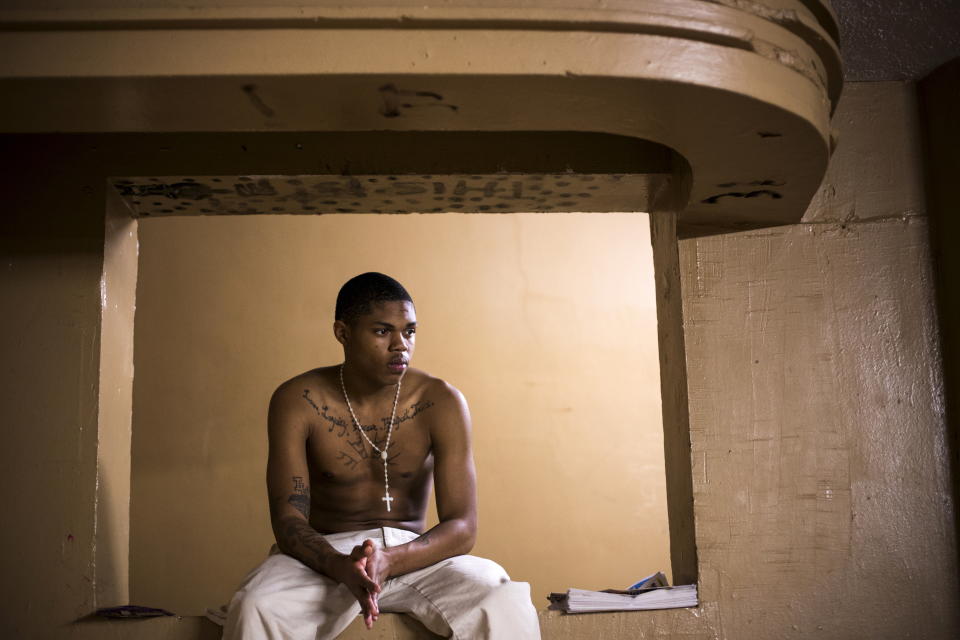

Johnny Perez, who spent 13 years in prison for first-degree robbery, vividly remembers solitary confinement.

“If you close your eyes for a second and you reach out both hands — imagine that both of your hands can touch both walls of the room,” Perez, who currently works as a criminal justice activist as the director of U.S. prison programs for the National Religious Campaign Against Torture, told Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender. “That's how small it is. The cell is a little bit longer than your bed, except that I'm six feet tall. So when I stretch my legs out, I can touch the edge of the bed. So a lot of times I used to sleep with my knees tucked into my chest. The room is very small, very quiet, very hot in the summer, very cold in the winter... During the day, sometimes it gets so noisy listening to the yells and sounds, and of other people who are locked inside of their cells, that it's really hard to sleep. Psychologically, you try to escape because there's really nothing to do.”

To pass the time, Perez would sleep all day — but that meant he would be up all night — and he read. Prisoners in solitary were allowed two books a week, 10 pieces of mail at a time, five magazines, and 10 pictures. At the same time, those in solitary are only allocated one set of clothing and only one layer of clothing at a time aside from underwear. And the toilet may or may not work.

“The toilet is right next to the bed,” he continued. “So when you lay down, the toilet is going to be as close to you in the bed. There were times when I would put my head there the way, but because, of course, correction officers have to see you when they walk by to make sure that you didn't kill yourself, commit suicide or harm yourself in any way, you have to lay in a bed in a way the officer can see you and that a lot of times is your head directly adjacent to the toilet. If you have a good cell, the toilet will flush. If you have a bad cell, the toilet won't flush. If you need a fix, it can take days for that toilet to get fixed, you get one roll of toilet tissue per week.”

If he ran out of toilet paper, Perez said he would have to “get creative” about how to replace it. Collecting toilet paper wasn’t an option: That could bring a misbehavior report for excess property, which would lead to more time in solitary.

As for eating, meals were set at a strict schedule: The first meal at 7:00 am, the second meal at noon, and the last meal at approximately 4:00-5:00 pm, meaning he would go over 14 hours without eating again.

“So you have to be mindful about how much you exercise,” Perez said. “You have to be mindful about how much you talk. You have to be mindful about how much energy you use, because you're going to be famished. I went in weighing 175 and went out a weighing about 155 after doing 10 months straight in solitary.”

This is part 3 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the prison industry. Listen to the series here.

‘We have this need to hear a human voice and to touch people’

Approximately 61,000 individuals were placed into solitary in 2017, out of 1.49 million people incarcerated, according to research from Yale University School of Law. For anyone who has experience solitary confinement, the severely confined space and various restrictions clearly take a toll on mental health.

“We have this need to hear a human voice and to touch people,” Perez said. “There's this study with music and this ecosystem of how we're all connected and in solitary, the most dehumanizing pieces are the fact that you have little to no meaningful human interactions. The only person that I spoke to was the same person, the officer that brought me my food three times a day or that walked by my cell to ensure that I didn't commit suicide. But when this one person doesn't talk to you, when this one person doesn't even look at you sometimes for days or weeks at a time, it does kind of chip at you a little bit. When you don't have nobody to talk to, you'll find that you'll end up talking to yourself, you'll talk loud.”

In New York, between 2015 and 2019, “the rate of suicide by persons in solitary confinement was more than five times the rate for the rest of the New York prison population,” according to the New York Campaign for Alternatives to Isolated Confinement. And, according to the data, at least 1/3 of all suicides that occurred in solitary confinement in 2019. And the rate of suicides in solitary in state prisons was 10 times the national prison suicide rate.

Perez would sometimes sing a song out loud or sometime think out loud. But it soon turned into “full-blown conversations” with himself.

“Looking from the outside in someone will say, ‘Wow, this person is losing it there. They're going crazy. Look at them. This is why they're in there,’” Perez said. “But another analysis would say, ‘It's not that this person's in there because he's acting like that. He's acting like that because he's in there.’ And it's a different perspective because it allows people to understand that if you are locked in a cell for eight months without nobody to talk to, and you can only see about six feet in front of you, hence why I still wear glasses to this day. After a while, yeah you're not going to act normal because this is not a normal environment.”

After his release, Perez was diagnosed with trauma by a psychologist, and much of it is tied to his time in solitary. He also now wears corrective lenses because his eyesight was affected by the experience without quality lighting.

“The system is so backwards that it doesn't do what it's supposed to do,” Perez said.”If we have a correctional system that is supposed to correct behavior, we have to ensure that that same system does not exacerbate that very behavior in which it is trying to change. ... So we get into the cyclical behavior where I'm reacting to my environment, you punish me, damage me. Now I come out and I react even worse because of the damage.”

This is part 3 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the prison industry. Listen to the series here.

‘I literally got into a fight the same day’

Perez’s first interaction with the legal system was when he was 11 years old and got caught stealing candy from a store.

“I remember the store owner literally grabbed me,” Perez said. “He called the cops and I spent about four days in a precinct for stealing the snicker bar. I think those were some of my early forays of having engagement with the legal system. And after that, I think after those, in those young, formative years from 11 to 15, I had a lot of interactions with police officers for... Some of the things were crimes per se, I was stealing out of the store or I'm hanging out outside or let's say drinking publicly.”

At 16 years old, Perez was arrested and sent to Rikers Island, a jail complex on New York City’s East River. It’s one of the largest correctional institutions in the world — and also one of the most controversial. Up until 2018, teenagers were imprisoned there as well, even if they were just awaiting trial and hadn’t actually been found guilty of a crime. In 2017, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced plans to shut down Rikers Island within 10 years. (In October 2019, the New York City Council voted to close it down by 2026.)

“If you've never been to Rikers Island, you go through a number of different emotions,” said Perez, who spent 10 months at Rikers. “One, you would just go through complete shock in the sense that it's a large institution, it's nine different buildings on the Island. So there's nine different smaller jails. There used to be more, but they've been closing one little by little and it actually operates like a prison and as we know, prison is where you go after you get sentenced in jail, so where you're held before you have your day in court. And when you go there, the place is really rampant with violence. And I was there as a 16-year-old and the minute that I walked in, I literally got into a fight the same day.”

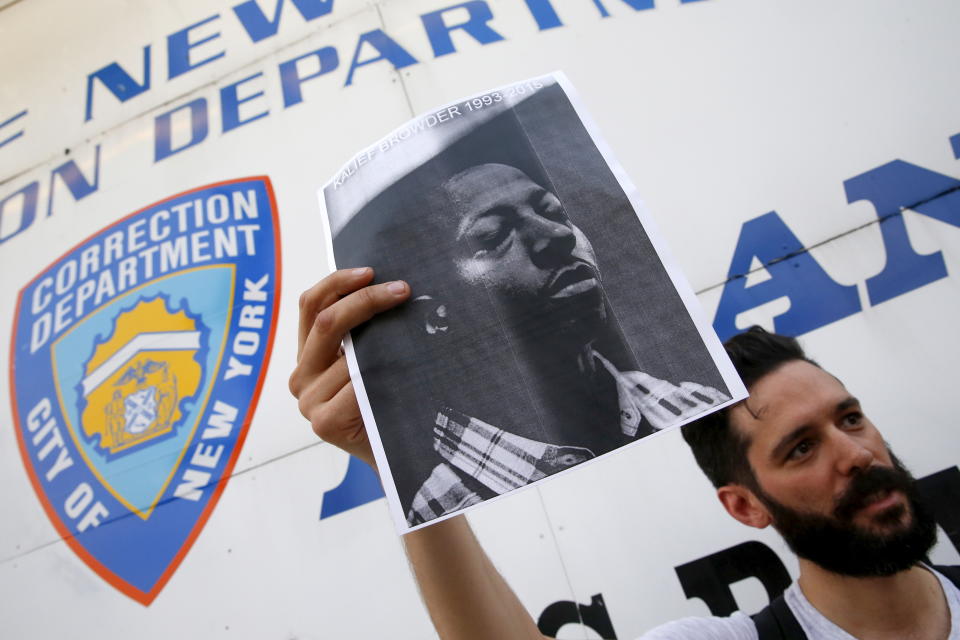

One of the most notable teenage cases related to Rikers is that of Kalief Browder, a 16-year-old accused of stealing a backpack. Because his family couldn’t afford his $3,000 bail, Browder ended up being imprisoned at Rikers Island without a trial or conviction for three years. Two of those years were spent in solitary confinement, even though he was still a juvenile in the eyes of the law.

“You go in, they put you in this large area, which is one large cell called the bullpen,” Perez explained. “There's about 30 to 40 men standing in there. Some people haven't slept for days. Some folks haven't showered for days; the toilet doesn't work; the sink might only spit out a little bit of water; there's one phone.”

Although Browder’s case was later dismissed, he committed suicide a few months after his release. Some experts cited the psychological trauma he experienced within solitary confinement as a factor in the choice to take his own life.

Adriana is a reporter and editor covering politics and health care policy for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.

This is part 3 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the prison industry. Listen to the series here.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance