From slavery to BLM: the ups and downs of 200 years of Guardian race reporting

Fifty years ago, as the Guardian marked its 150th birthday, the then editor, Alastair Hetherington, reflected on the changes he had seen since he joined the paper 21 years earlier. Intriguingly, he singled out social forces striving to upset “racial harmony”, and promised resistance.

But in the same 1971 edition, a gallery of images of the senior staff showed how far the paper had to go. All men. All white. In its first 150 years, the number of journalists of colour employed by the paper could be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Unsurprisingly for a 200-year-old institution, the Guardian has not always got it right in terms of race coverage. An early article from 1823 regretted the “cruelty and injustice of negro slavery”, but also noted that “amongst all the obvious disadvantages of slave labour, there is none more striking than its tendency to deteriorate the soil”. That set the tone for decades of coverage that often failed to empathise: during the US civil war, the Manchester Guardian was so concerned about the cotton trade that underpinned it that it sided with the slave-owning south.

The arrival in the UK of Yemeni seamen after the first world war is marked mainly through the “indignation” felt by dock workers at increased competition for work. Race riots in south Wales in 1919 run under headlines such as “Serious racial riots at Cardiff: Three whites killed. Negroes attack with razors”. (In fact, four were killed, including the Arab seaman Mohammed Abdullah.) Remarkably, 40 years later, headlines about Notting Hill riots similarly focused on the antics of immigrant rioters, and not the more sinister angle of provocative white mobs, though one important article acknowledged the racism faced by Caribbean migrants.

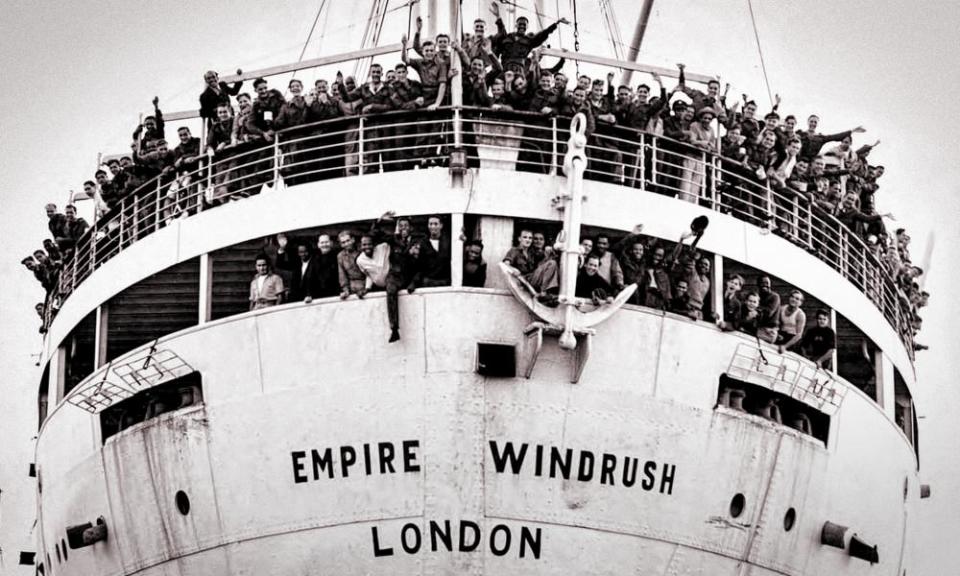

The arrival of the Empire Windrush warranted a news story – but no follow-ups on how the new arrivals found their feet, or not, in postwar Britain. US coverage of civil rights was patchy and even offensive (Rosa Parks is referred to as “the stubborn woman who started it all”; others are described as “sassy Negroes” or “a fat coloured wench”) until the reportage of WJ Weatherby served as a partial corrective.

The word “racism” – or its precursor, “racialism” – barely features in the paper until the mid-1960s. As the anti-racist movement began to grow, so did the paper’s coverage – but it was still far more likely to cover policy and process than the predicament of communities of colour. A letter to the paper by an activist chastised the Guardian for giving so much space to a 1976 Enoch Powell speech attacking the Home Office for an error they’d made concerning immigration figures.

Related: 200 years of US coverage: how the Guardian found its feet stateside

Lindsay Mackie managed to establish an unofficial beat of race correspondent in the 1970s, reporting on the 1976 uprisings in Southall and leading an investigation into the increased violent attacks against black organisations the following year. Mackie would go on to cover the New Cross Fire and the Brixton riots in 1981. “The Guardian was regarded as a place where you’d get a truthful version of yourself or of your community,” she recalled.

The Guardian was not just the first British national to hire a black sports writer in CLR James, but also the first to hire a black African stringer to cover the continent, Nathan Shamuyarira. But it was not until the 1970s that the London newsroom hired staff reporters of colour – a brief stint for Rafiq Mogul on the City desk, followed by Shyama Perera in the newsroom in 1981. At 23, she stood out for her age, Sri Lankan roots and background, having left school at 16. “My race wasn’t an issue in those days, really, it was still class and gender,” she says. “Everyone always used to joke that the Guardian office was like the JCR, which was the junior common room in Oxford, and I didn’t have a bloody clue what the JCR was and why this was considered both funny and wonderful.”

Perera had a background in the tabloid press and found the Guardian newsroom rather dull by comparison, describing writers sat at their desks surrounded by “huge tomes”. “I was the most exciting thing in my view in the Guardian newsroom, honestly, if it wasn’t for the typewriters, it would have been like being in a morgue”.

Despite that, Perera has fond memories of the paper, which she says she loves. In her opinion, however, it often came across as the “middle class telling the working class … what we should all be doing and how lucky we are to be supported by them but they don’t look like us, sound like us or really represent us”.

When Joseph Harker, the paper’s current deputy opinion editor, joined in 1992, he was also surprised by the “poshness” of the newsroom. “I felt that this wasn’t the kind of organisation for me, both from a race point of view and a class point of view.” However, he said he looked at the other Fleet Street options and thought: “They must be even worse.”

Having spent five years working in the Black press, campaigning against racism and inequality, he decided he had to do something to try to change it. Initial attempts fell on deaf ears: he recounts raising an objection to the way the Guardian was covering something and a senior editor saying: “You can’t teach me anything about race, I’ve read Eldridge Cleaver.”

“That was typical of the attitude of the place in the 90s, where it was an almost exclusively white institution, but because there were no people of colour, there was no one to question the whiteness of the place, and therefore they could all feel like experts on race, because then they were – among their own peer group,” Harker says.

It wasn’t until the Macpherson report in 1999 that an opportunity for meaningful change presented itself. The racist murder of Stephen Lawrence in 1993 and the subsequent inquiry that exposed and defined institutional racism would change Britain, prompting debate up and down the country.

The Guardian was no exception. On the eve of the report’s publication, the Guardian carried an op-ed citing Lawrence’s death as a “racist atrocity” but lauding the inquiry. Harker voiced his objection the following morning, pointing out that the column had failed to mention that Lawrence’s killers hadn’t even been brought to trial. The only other journalist from an ethnic minority in the room, Kamal Ahmed, backed him up. That was it, Harker says. As the week continued, he raised more issues, leading to him writing a comment piece arguing for the head of the Met police to resign. The Guardian’s leader that week disagreed with him – but included a line mentioning the case he had set out.

At the same time, another rumbling issue of resentment came to the fore. A heated row had been brewing over the pub that some Guardian journalists drank in. An allegation of racial abuse had led journalists of colour to propose a boycott. Although agreed, it was largely ignored – until that week. A union motion to reaffirm the boycott was proposed. Despite heated arguments on both sides, it passed.

For Harker, this succession of events amounted to a “now or never” moment.

He says black people “were covered in the Guardian better than we were covered in any other newspaper, but it was always from a white perspective”. The dozen or so minority ethnic staff met as a group for the first time and arranged a meeting with Alan Rusbridger, the then editor. He was receptive to their ideas, and agreed, among other things, that the paper would advertise entry-level jobs for the first time. The Positive Action Scheme, which still runs, would also eventually come from that initial meeting. The Scott Trust Bursary scheme, launched in 1987 under Rusbridger’s predecessor Peter Preston, also opened the way for young minority ethnic journalists to get their break, including Gary Younge, Lanre Bakare and Poppy Noor.

Younge credits Harker with being absolutely central to the task of changing the institution’s complexion, but also its culture. “That was an aspiration embraced from the top, but shaped, in no small part, from pressure from below,” he said. “[The current editor-in-chief] Kath Viner later built on this work, and in terms of recruitment, ramped it up.”

The fruits of that labour mean that for many anti-racism organisations that sprang up around the time of Macpherson, the Guardian has been what Simon Woolley describes as “the first port of call”. Since he founded Operation Black Vote (OBV) in 1996, Woolley says, the paper has been “writ large” in their history. “I, like many black activists in the field, have always seen the Guardian on that frontline” of the fight for racial equality, he says.

In the years since, the Guardian’s race coverage has deepened, from Hugh Muir’s Hideously diverse Britain series and the exposure of the Windrush scandal, to reporting projects such as The colour of power in 2017, The Counted in the US, the Young British and Black project from 2020 and Indigenous affairs reporting in Australia. There are now dozens of journalists of colour, including reporters, video producers, columnists and subeditors.

Dr Omega Douglas, a journalist and academic who researches media diversity, describes Younge’s writing as “a breath of fresh air”. Younge’s two decades of work in the US were instrumental in reshaping the Guardian’s coverage of racism, his valedictory piece a powerful indictment of the injustice that would lead all the way to George Floyd.

“His words spoke to me and for me on many levels. Levels on which I’d never felt addressed by Britain’s mainstream press before,” she says. However, Douglas, who wrote her PhD thesis on media coverage of sub-Saharan Africa, has criticised the Guardian’s reporting on Africa for sometimes falling into a pattern of “reporting on the global majority through the narrow lens of development”.

The Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 provided new impetus. Discussions were more vocal because of the increase in the number of employees of colour. The push led to a race action plan, resulting in several new positions focusing on race, including the appointment of two community affairs correspondents, Aamna Mohdin and Nazia Parveen.

The pair had both covered race as general reporters, including the BLM protests and Covid’s disproportionate impact on BAME communities. “It is a specialism in its own right, like health and social affairs, which requires a dedicated reporter,” said Mohdin. “I’m pleased the Guardian agreed and responded to last summer’s cry for racial justice with the creation of these two roles.”

Parveen said the role spoke to the part of her previous job as a general reporter that she had most enjoyed: having the “opportunity to take a step back and spend time in underrepresented communities”. Citing her reporting on Muslim communities protesting about LGBT teaching at schools, she said the stories came “not because I was parachuting into these communities, but because I know these people. I know how to, metaphorically, speak their language. I personally represent in our newsroom the underserved audiences we want to reach and better represent.”

A current photo of Guardian staff would show far more diversity today than 50 years ago. But diversity is not just about looking different but acting differently. If the absence of journalists of colour was a problem, their/our presence presents new challenges in transforming the culture of the paper and its coverage.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance