‘A rejected success.’ 50 years later, Charlotte still reckons with school equality

Listen to our daily briefing:

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Alexa | Google Assistant | More options

Vera and Darius Swann stood before the all-white school board one evening in early September.

It was 1964 — a decade after Brown v. Board of Education. Despite the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, schools nationwide remained segregated. The Swanns wanted their son, 6-year-old James, to be reassigned from the all-Black Biddleville School to one nearby, Seversville, which was integrated.

The board unanimously refused. The Swanns told the Observer they would consider next steps. They followed through — through the NAACP, they took it to court.

A few years later and exactly 50 years ago, on April 20, 1971, the Supreme Court made a decision — justices ruled in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education that the school board must create a busing plan that would desegregate the district. Federal courts would use the framework to finally plant seeds of integration in districts nationwide.

Five decades later, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, one of the largest metro districts in the country, still reckons with inequality.

Though much progress has been made, much has been reversed, too.

A father’s legacy

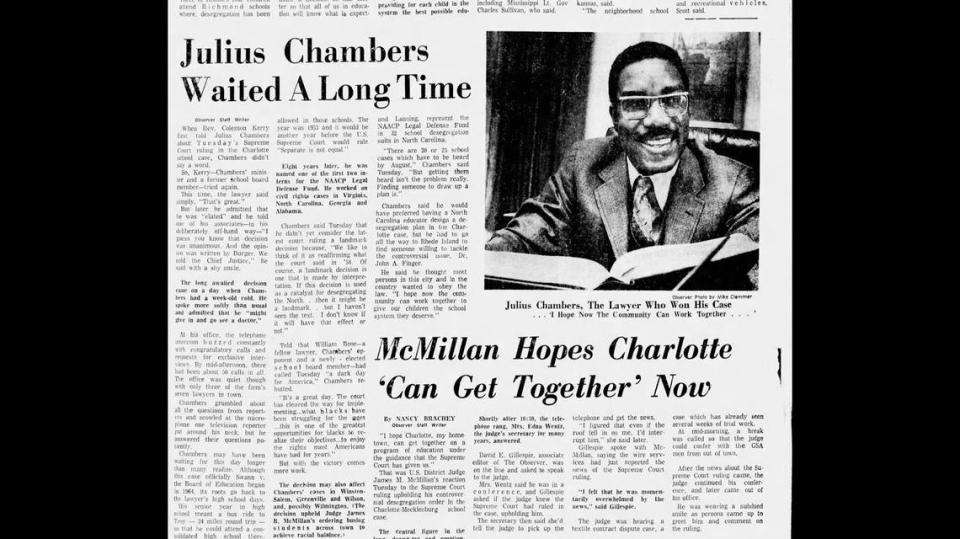

Derrick Chambers was five years old when his father Julius argued the Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education case.

“... He would just be steady at work, dealing with this case,” he remembers.

“He knew it was a pivotal moment to get busing in because that was the only way you could ensure kids could go to schools throughout the city.”

His father won, and Derrick, along with the district’s thousands of Black students, reaped the benefits. Over the next two decades, Charlotte became a model for the rest of the country.

Julius Chambers was most proud of his work on the Swann case, Derrick Chambers, now 54, said.

“He knew the significance and the impact it would have not just on Charlotte and North Carolina, but the impact it would have on the nation.”

Before busing, schools were deeply racially divided. Districts nationwide had dragged their feet to integrate schools after Brown v. Board of Education and the Swann case provided an immediate solution, a mandate, to correct the imbalance.

Growing up, Derrick Chambers went to desegregated schools with some of the most affluent and influential white families in Charlotte. He started elementary school at Oakdale, off Beatties Ford Road. Then he switched to Irwin Avenue, which is where he first met many of the white students he would later go to high school with at West Charlotte.

“I would mix with a lot of white kids. They’d come spend the night at my house, and I’d spend the night at theirs,” he said. “It gave me the opportunity to have relationships with other people outside of my race, as a direct result of desegregation.”

And he remembers the spotlight he had on him, at each school he attended.

“My father’s legacy impacted me the whole time I was in school,” he said. “It opened doors for me, but it also brought the pressures of life — to carry the weight of your last name.”

From his own segregated school to the Supreme Court — in 1971, Julius Chambers prevailed

The shift to choice

In the late 1970s and ‘80s, there began a gradual build, politically and socially, to disband federally ordered busing programs that had sped up integration of public schools across the nation, particularly in the South. Some claimed the courts’ hand in approving districts’ student assignment strategies was no longer needed, being decades removed from the end of legalized segregation in public schools.

By the early ‘90s, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools was already attempting to decrease its reliance on busing while also continuing integration.

A new plan that CMS implemented in 1992 aimed to decrease the number of students being bused.

The strategy revolved around magnet schools. A certain number of Black and white students were allowed to attend each school, frustrating many white families who were denied entrance to some — like the Capacchiones.

William Capacchione sued the district in 1997 when his daughter was denied entrance into a magnet school.

The family’s case against CMS would lead the courts to overturn Chambers’ victory in the landmark Swann case. CMS board members were once again saddled with the responsibility of coming up with a new plan for school assignments. The Supreme Court refused to hear the Capacchiones’ case, letting stand the family’s victory in a lower court, and the school district was left to build racially balanced schools inside severely segregated neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the Capacchiones left town.

The board’s solution came in the “School Choice Plan,” which divided Charlotte into zones based on neighborhoods. Students could either stay at their neighborhood school or rank their top three choices of other CMS schools — but transportation would only be provided to their home school or magnet schools.

Derrick Chambers says he knew then — and his father knew, too — that this would reverse the success achieved through Swann. Julius Chambers died in 2013.

“He knew that when you went to neighborhood schools, it was going to be a disaster, that you’d never have equality. That’s what hurt him the most,” his son says.

“Those people destroyed something that was significant to everyone’s life, and then they moved. They don’t realize the impact it had on these schools.

“How do you have dreams when you leave your home and go to school in the same neighborhood where you see crime and everything else?”

Social policy researcher Amy Hawn Nelson says it’s more than that.

“People think desegregation ended with Capacchione, but that’s not quite accurate,” she said. “Our segregation efforts really stopped in the mid-’90s with our move toward magnets and school choice as the main guiding force behind student assignment.”

His father’s legacy, Derrick Chambers said, can never be tarnished, despite the steps backward CMS has taken in recent years. The district is the most racially segregated in the state, the Observer reported in 2018, citing a study from the North Carolina Justice Center’s Education & Law Project.

Nelson, who grew up in south Charlotte, said white parents make decisions that ultimately benefit white kids — so giving families the choice ultimately always results in inequity.

“There are ways to work the system and white parents play it like a violin,” she said. “Every system was built for us. Like, we do paperwork really well, we navigate systems really well, because we designed them.”

Nelson says it’s no coincidence that all of the maps that show where the most low income neighborhoods are, where most food deserts are, and where the lowest reading proficiency is look the same — it’s all connected.

“CMS is not working fast enough to fix it,” Derrick Chambers said.

“Everything was destroyed. That was one of the most disheartening feelings, and he took that to his grave,” he said of his father.

A new demographic

Mecklenburg County’s population has more than doubled in the past 25 years.

It’s difficult to compare today’s school enrollment figures by race to data from decades past, Nelson says. Alongside countywide population growth, CMS’s enrollment has changed substantially. During the Swann-era, for example, there were few Hispanic students in Charlotte schools.

In the past decade, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools has seen a substantial increase in non-white students.

The Charlotte Observer analyzed the demographic data for every school that has been open continuously for the past 10 years, around 150 schools. In those, there are now slightly more Hispanic students than there are white students.

The district’s non-white population in that set of schools jumped from 65% in 2010-11 to 74% this year. An increase in Hispanic students fueled much of that growth, an Observer analysis found. The number of Hispanic students increased about 75% in the past decade, data show.

Hispanic students now make up about 28% of CMS students — compared with about 16% a decade ago.

White students now make up 26% of CMS students, data show, down from 35% in 2010.

Black student enrollment decreased from 41% of CMS students to 36%.

In the past decade, CMS has fewer schools with overwhelmingly white student populations. But racial balance remains elusive.

The Observer analyzed data from CMS showing student demographics by school. Few come close to resembling the district’s overall diversity — that was the case 10 years ago, and it was that type of division that Chambers fought to address in the Swann case.

Before Chambers’ victory at the Supreme Court, public schools had used busing, not as a way to conquer racial segregation — but as a way to uphold the status quo, Nelson says.

“The Swann case is really important for multiple reasons ... Before, busing was used as a tool to deny transportation and segregate. But it had never been used to desegregate and that’s an important distinction — allowing it as a remedy instead of causing harm,” she said.

“So Swann was a success, but it was a rejected success.”

Erosion of equality

When CMS Superintendent Earnest Winston first arrived in Charlotte in 2002 to work for the Observer, he somewhat knew of the district’s legacy.

Working his way from reporter to teacher to administrator to superintendent, he has become intimately acquainted with the struggles and triumphs of the district.

Though progress has been made, Winston acknowledges CMS still has a long way to go.

“We’ve seen some erosion of the elements that helped desegregate Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, there’s no denying that,” he said. “There are so many factors that play into educating kids. Among them: our housing patterns, economic structures, social mobility. I really think this work is journey work. It’s not as if you wake up one day and the issue is solved.”

Despite the city’s increasingly diverse population, Charlotte’s neighborhoods are distinctly segregated by race. So it makes sense that a district that relies on neighborhood schools and parent choice would be segregated, too.

“We believe as a school district that diversity is one of our greatest strengths,” Winston said. “All kids benefit when schools are more diverse.”

He’s right.

Research shows integrated, diverse schools have academic, social and emotional benefits for all children.

“With the anniversary approaching, for me, it is a reminder of how much work remains to be done to create equitable opportunities for all students,” he said last week in an interview. “We know it’s attainable. It is something we aspire to again.”

Olympic High School junior Joseph Asamoah-Boadu lives right down the road from his school. Olympic is a diverse school, with majority Black and brown students like Asamoah-Boadu. And it has strong community partnerships and opportunities for their students.

Asamoah-Boadu appreciates going to a school where his classmates share many of his experiences, and more teachers look like him.

But he still wonders what it would be like if he could go to Myers Park or Ardrey Kell. Both schools are closed for reassignment due to capacity, according to the district’s website, and only students who live nearby can attend.

“There are many more opportunities and facilities,” he said. “Race and class are intertwined in this country, and people from these high-income, majority-white schools are able to succeed more easily… I feel as if we’ve kind of regressed or haven’t made much progress since the Swann case.”

Gavin Off contributed to this report.

The ‘certain indignities’ of growing up Black on a street named after a slave owner

Why have thousands of smart, low-income NC students been excluded from advanced classes?

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance