Phil Spector brought joy to pop music – and misery to so many lives

Three years before his death in 2006, I interviewed Gene Pitney. Talk inevitably turned to Phil Spector. He had written Spector’s real breakthrough record – the Crystals’ 1962 No 1 He’s a Rebel – unequivocally one of the greatest singles in pop history, a perfect cocktail of soaring melody, echo-drenched production and Darlene Love’s exuberant vocal. A year before that, he’d sung Every Breath I Take, which, with its rumbling timpani, overload of backing vocals and dramatic orchestration, was one of the few early Spector productions to hint at the more-is-more Wall of Sound approach that would make him a legend. And, moreover, Spector was, as Pitney put it, “kind of a hot news item”: he was awaiting trial for murder.

Like a lot of people who knew Spector, Pitney seemed horrified yet oddly unsurprised at this turn of events, as if something like that was bound to happen sooner or later: the booze, the drugs, the evident instability, the obsession with guns and the history of violence towards women. Spector, he suggested, had been in trouble from the start. “I had dinner with him the first day he arrived in New York, and he said to me that his sister was in an asylum and she was the sane one in the family,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘Wow, where did that come from?’”

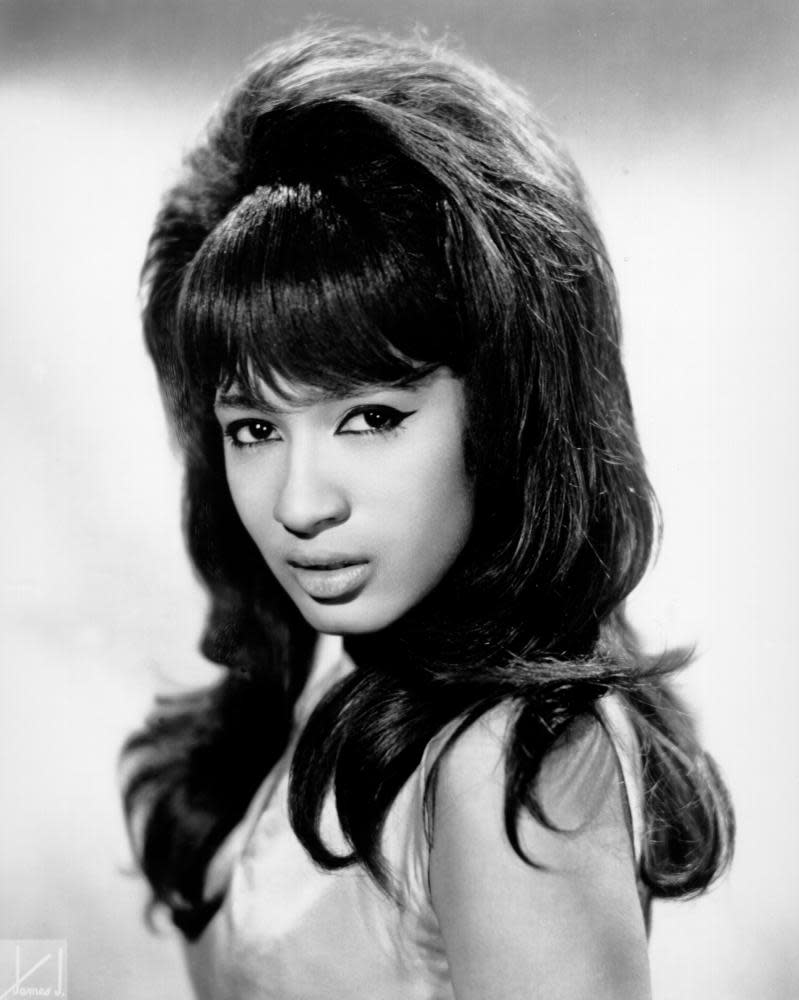

The truth is that everybody knew what Phil Spector was like long before he killed Lana Clarkson: by his own account, a childhood scarred by his father’s suicide and riven with bullying – by his mother, by his schoolmates – had left him “with devils inside me”. His ex-wife Ronnie Spector’s 1990 autobiography Be My Baby laid bare the full horror of their marriage: the house surrounded by barbed wire and guard dogs; the threats to kill her, either himself or via a hitman; the gold-plated, glass-topped coffin he installed in the basement and threatened to display her body in after she was murdered.

Related: Phil Spector obituary

The stories about recording sessions that had gone wildly awry were legion too: he shot a gun into the ceiling of LA’s A&M Studios while working with John Lennon in 1973; he pointed a loaded gun at Leonard Cohen’s throat – Cohen subsequently compared him to Hitler – and according to their bassist, Dee Dee, he held the Ramones hostage at gunpoint during the making of 1980s End of the Century. As writer Sean O’Hagan once noted, in a sense even the extraordinary music he made between 1962 and 1966 was an “act of revenge on a world that had wounded him beyond repair as a child”; every hit a vindication that he hoped would assuage his own deep-rooted feelings of inferiority.

But He’s a Rebel, Da Doo Ron Ron and Be My Baby don’t sound like acts of revenge; they sound utterly joyful, innocent. A lot of attention is understandably drawn by Spector’s tendency to overload as a producer – the umpteen musicians required to make his singles, the doubling and tripling up of instrumentation. But Spector’s excess baggage never weighed his records down. They barrel gleefully along, even the gloomiest of his ballads – the Ronettes’ extraordinary Is This What I Get for Loving You? and I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine, the latter arguably the artistic pinnacle of the Wall of Sound years – feel remarkably light on their feet. He was somehow capable of creating singles that were sonically dense but also had a sense of space. They never sound over the top or claustrophobic, with the possible exception of Ike and Tina Turner’s River Deep, Mountain High – Spector’s favourite among his works, but a song that might have benefited from a more stripped-back approach.

The US failure of the latter sent Spector into a tailspin from which he never truly recovered. His next high-profile job, on the Beatles’ Let It Be, was a mess. The source material wasn’t their finest – John Lennon memorably called it “the shittiest load of badly recorded shit with a lousy feeling to it ever” – but nevertheless, Spector submerged good songs in inappropriate orchestral and choral syrup. His production of George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass was similarly controversial – “Too much echo,” Harrison complained years later, his son Dhani claiming that “making the album sound clearer was one of my dad’s greatest wishes” – but his work on Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band and Imagine albums was fantastic: stark, minimal, the opposite of what you might expect, with only the fabulously explosive drums on the 1970 single Instant Karma! an echo of his 60s work.

The rest of his career yielded only scattered moments that suggested his former greatness, most notably the tracks he recorded for Dion’s Born To Be With You in 1975. He ended his recording career being fired by, of all people, British indie rock band Starsailor. At the time, it seemed an ignoble fate for someone who had once presided over a succession of era-defining classics, whose work spurred Brian Wilson into creating the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, regularly heralded as the greatest album of all time, and whose 60s sound you heard echoes of everywhere, not least in the blare of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band. But, as it turned out, far worse was to come.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance