Pauline Tinsley obituary

The soprano Pauline Tinsley, who has died aged 93, was idolised by audiences and critics alike for her peerless performances in a wide range of repertoire, yet was consistently passed over by the operatic establishment.

The blazing intensity of her singing in such roles as Turandot, the Dyer’s Wife in Die Frau ohne Schatten, Elektra or any number of Verdi heroines could be searing and imprinted itself on the memories of countless operagoers, but notwithstanding acclaimed appearances with Sadler’s Wells Opera (1963–74, the year in which it became English National Opera) and Welsh National Opera (1962–72 and 1975–81), her talents were unaccountably neglected later in her career, both by British national opera houses and by commercial record companies.

She made her Covent Garden debut in 1965 as the Overseer in Elektra (dominating five maids that included Gwyneth Jones, Elizabeth Vaughan and Helen Watts), but it was not until 1971 that she returned there, as Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera, on which occasion an announcement from the stage that she would be standing in at short notice for an indisposed singer was greeted by a shout from the gallery: “And about time, too!”

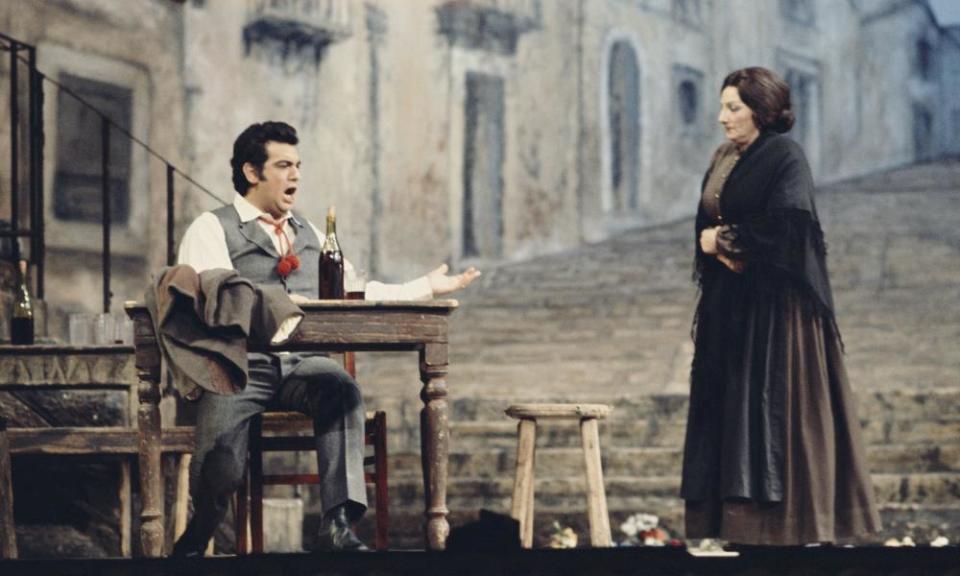

She was invited back to sing Santuzza in Cavalleria Rusticana (opposite Plácido Domingo), Mother Marie (in Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites), Lady Billows in Albert Herring and some minor roles in the Royal Opera’s Ring cycle, but her potential as one of the leading dramatic sopranos of her day, commanding the stage in the big Wagner, Verdi and Strauss roles, usually had to be glimpsed elsewhere.

The enormous success of the WNO’s Elektra, directed by Harry Kupfer (1978), with Tinsley in the title role, led to a flood of offers to sing the role in European and US houses. In both that role and that of the shrewish Dyer’s Wife, she was able to scythe through massive orchestral textures with a tone that was adamantine yet full of humanity. A diminutive figure, she nevertheless brought to those roles the dramatic conviction, stamina and projection for which she was known.

In the early part of her career she had sung lighter-voiced roles such as Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute, Despina in Così Fan Tutte, Romilda in Xerxes (for the Handel Opera Society) and Donna Anna in Don Giovanni (for the Chelsea Opera Group). Her voice, especially at this stage, also had a coloratura quality suitable for bel canto roles.

Making her professional debut in 1961 as Desdemona in Rossini’s Otello, at what was then the St Pancras (later Camden) town hall, she sang with what one critic described as “quite the right panache and control”. In the title role in Donizetti’s Anna Bolena and as Elizabeth I in the same composer’s Maria Stuarda, which she sang at the New York City Opera opposite Beverly Sills, she proved to have a suitably flexible instrument that could also provide an exhilarating delivery.

Plans to go on to sing in Roberto Devereux and Anna Bolena with Sills in New York were abandoned when the two sopranos fell out in rehearsal: “Beverly didn’t like the competition,” opined Tinsley.

When she sang Elizabeth I again, this time opposite Janet Baker, at the Coliseum in 1973-74, even those who found her tone occasionally “thin” and “squally” had to admit that the characterisation was telling. But she was not invited back for 15 years, and then to do five performances of the Mother-Witch in David Pountney’s production of Hansel and Gretel. She proved to have lost little of her vocal command, conjuring up a Witch who was both grotesquely funny and alarmingly neurotic. Her sadistic Kabanicha in the 1989 ENO revival of Katya Kabanova was equally compelling.

Born in Wigan, Greater Manchester, the daughter of William Tinsley, a railway worker, and his wife, Esther (nee Tonge), she studied classical ballet before concentrating on singing, attending the Northern School of Music in Manchester and then the Opera School in London. Joan Cross was a formative teacher, as was, later, Eva Turner, with whom she studied roles such as Aida and Turandot, repeatedly returning to her for coaching.

By the early 1960s she was married and had her first child, a boy who used to attend rehearsals with her in his pushchair. The first big break in her career came in 1962, when Charles Groves invited her to sing Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro at the WNO. The following season she added Elsa in Lohengrin to her repertoire, “so I sang Susanna on Tuesday and Thursday and Elsa on the Wednesday”, as she later recounted. By the time of her ROH appearance in Elektra she was pregnant with her second child, a daughter, who was born a few days after a performance as Verdi’s Lady Macbeth in London; 12 days later she was singing Elsa in Llandudno.

The large number of other roles she undertook included those of Leonora (The Force of Destiny) and Leonore (Fidelio, both versions) for Sadler’s Wells; Abigaille in Nabucco (a signature role), Aida, Turandot and the Kostelnička in Jenůfa for WNO. She also sang with Scottish Opera, Opera North, the Chelsea Opera Group and other companies.

To hear her in the larger Wagner roles (Senta, Kundry, Isolde, Brünnhilde, Ortrud) and in too many of the other major parts in which she flourished, one had to travel to mainland Europe or the US, however. As Isolde she was able to float a sensually beautiful line in the Liebestod that demonstrated an aspect of her vocal technique not always obvious elsewhere.

Her powerful Elettra in Idomeneo was captured in a Philips recording under Colin Davis, and she sings the Overseer in Solti’s recording of Elektra. Fortunately several dozen other performances have been preserved by the labels Opera Depot and Ponto, and by the Chelsea Opera Group. A valuable Chelsea recording of a 1977 Salome, though of inferior sound quality, documents a thrilling performance of Strauss’s opera under Nicholas Braithwaite, with Tinsley gloriously riding the orchestral flood and perhaps demonstrating the ideal Salome voice: lithe, penetrating, lustrous.

The steely ferocity of her stage persona, which could make her characterisations menacing, even terrifying, contrasted with the warm-hearted, down-to-earth, unpretentious individual who created them. She remained philosophical both about opportunities – and the lack of them: “I don’t say ‘I should love to sing at the Scala or at the Met’. If it comes, it comes; if it doesn’t, it makes no difference.”

Her husband, George Neighbour, predeceased her; she is survived by her children, John and Julia.

• Pauline Cecilia Tinsley, soprano, born 23 November 1928; died 10 May 2021

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance