Mini-skirts, bouffants and forgotten hits: The unsung women of the British Invasion

The year was 1964. Charming, disarming and identical in their haircuts, British boy bands came in their droves, bewitching teenage fans, alarming parents and putting Elvis’s hips to shame. The moment their Chelsea boots set foot on United States soil, all Americans could do was surrender.

Almost overnight, the pages of Billboard and Record World were brimming with black and white photos that depicted swarms of eager teenybopper fans, arms outstretched for a chance to get close to The Beatles, The Kinks, The Yardbirds and The Animals. Headlines alerted “The British Are Coming” and cautioned that, like a virus, “Beatlemania Sweeps US”. Even today when the subject of the British Invasion comes up, these bands are the ones exalted in the US for the music they made and the impact they had.

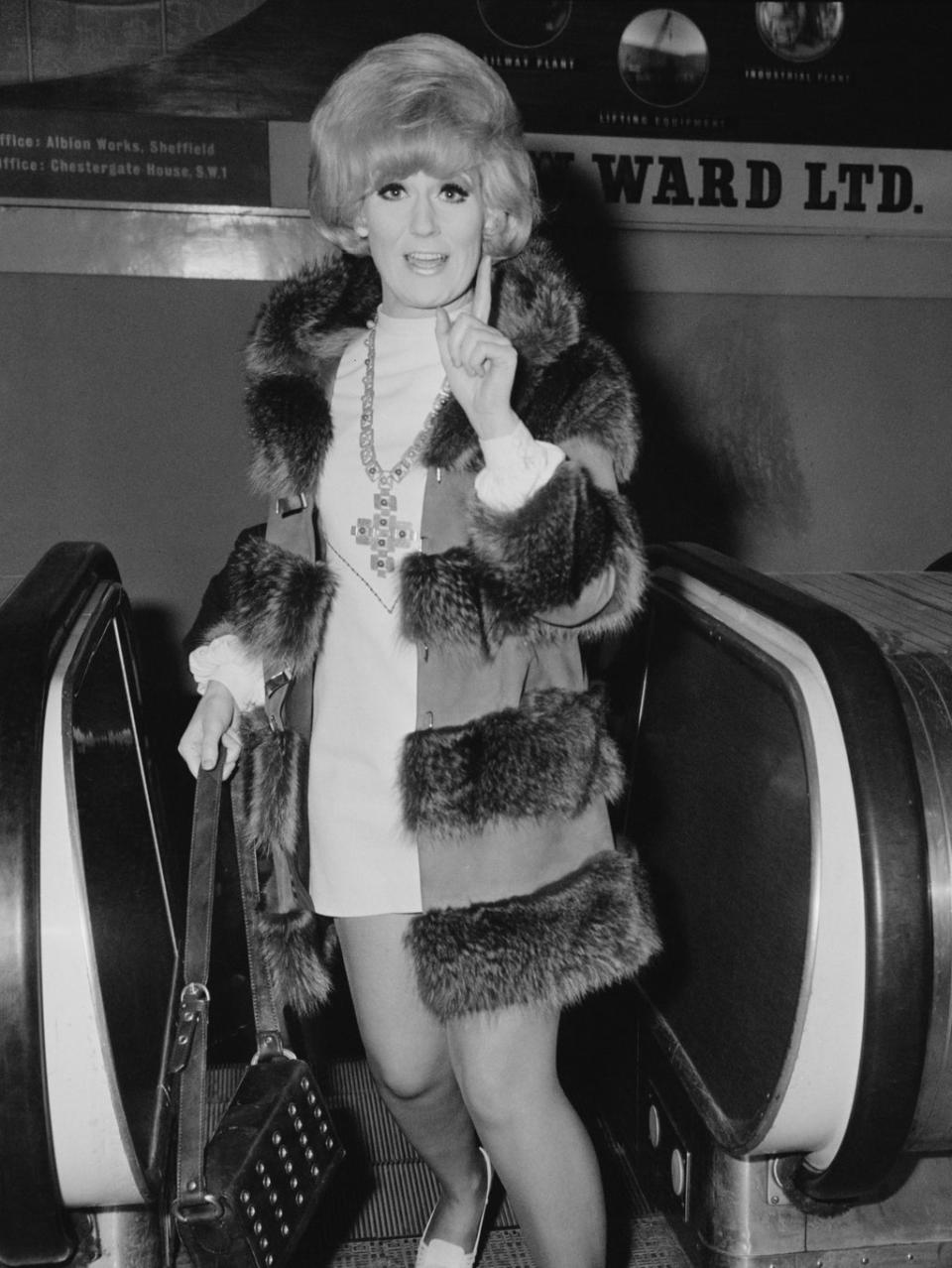

However, outside of mop-top mania, British solo female artists were another major export at the time. Dusty Springfield, Petula Clark, Sandie Shaw, Cilla Black and Marianne Faithful were all topping the charts during the days of “Can’t Buy Me Love” and “You Really Got Me”. These women commanded our attention 50 years ago, whether through their distinctive voices or cutting edge fashions – but, in the years since, their cultural contributions have become somewhat overlooked.

Ask Petula Clark, 89, about her aspirations, however, and she is nonchalant. “I wasn’t looking for a career in America,” she says now. “The thing about America is, they’ll only take you on if they like you. I was lucky because I had the song.” The song she’s referring to is “Downtown”, the delicate composition that hit the US like a tidal wave and became her first US hit. “America fell in love with the song, I just happened to be singing it,” she says modestly. Still, it got the ball rolling on a successful Stateside career: she won the Grammy for Best Rock and Roll Recording in 1964. Fourteen more of her songs would chart consecutively in the Top 40s.

Before 1964, Americans had only been privy to a smattering of Britain’s star quality. There were Shirley Bassey’s James Bond themes and Helen Shapiro’s brief turn as a teenage pop star, though at that time the concept of the solo female performer was still a fairly uncommon one in the US: many of the female pop and soul singers in the States came as package deals in the form of girl groups such as Martha and the Vandellas or the Shangri-Las (Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walkin’” would come two years later, in 1966). But these British women exhibited the power a solo performer could bring to the recording studio, and to the stage.

Possibly the most iconic of all was Dusty Springfield, whose life story is currently being made into a for-TV biopic starring a blonde-bouffanted Gemma Arterton. Springfield was one of the first Brits to secure a big US hit on her own with “I Only Want To Be With You”, in January 1964, at almost exactly the same time that The Beatles scored their first US No 1 with “I Want to Hold Your Hand”. Springfield’s charming brand of blue-eyed soul would go on to earn her eight more American hits.

A string of sweetly melodic singles, including the wistful “As Tears Go By”, put the 18-year-old Marianne Faithfull in the US spotlight a year after Springfield. While her name has become synonymous with the Swingin’ Sixties, she’s often better known for her romance with Mick Jagger and her rock’n’roll tendencies than she is for the British Invasion, though her music was a key touchstone. Hopefully, the forthcoming Ian Bonhôte-directed biopic of her life and career, starring Lucy Boynton, will offer a closer look.

While some British solo singers enjoyed only brief success overseas, their careers were still pivotal in shaping the music of the time. During the days of John, Paul, George and Ringo, Liverpool produced another Merseyside legend in the shape of Cilla Black. Her sound was poignant and her voice was bold. However, America took its time realising Black’s talent, even after she took Dionne Warwick’s “Anyone Who Had a Heart” to international acclaim in 1964. It wasn’t until her 1965 song “You’re My World” that she made it onto the charts.

And then there was Sandie Shaw, the oft-dubbed “barefoot pop princess”, whose version of “Always Something There to Remind Me” would unfortunately prove to be the sole jewel in her crown. She would never match its success in the US, yet her achievements, along with Faithfull, Springfield and Clark would be paramount when it came to inspiring future generations of solo artists.

One of those artists is British singer Rumer. “Sandie blows me away… barefoot and beautiful with this amazing voice…I feel annoyed that we haven’t got more of her,” she says. Rumer describes these women not only as phenomenal singers, but also as great interpreters of songs, who can elevate music written by others to greater heights. “I love great voices and I can totally see why America embraced [them],” she says.

I can totally see why America embraced them

Singer Rumer on the women of the British Invasion

Of course, their voices were one important reason: Springfield’s husky croon, Faithfull’s blossoming lilt, Black’s mighty bellow. But they also had an uncanny ability to seek out the perfect songwriting partners to send those songs sailing across the pond. Acclaimed British composer Tony Hatch, responsible for writing Clark’s “Downtown”, worked with the singer long after their first success. Other songs they created together include “Where Are You Now?” and “I Couldn't Live Without Your Love”. Dusty Springfield and Cilla Black, meanwhile, enjoyed collaborations with revered composer Burt Bacharach and lyricist Hal David.

Along with their sound, the Brits brought style, too. Many of them became poster children for a new kind of Sixties woman – one on the verge of breaking free from the shackles of Fifties womanhood. As skirts got shorter, hair a little taller and the kohl a touch heavier, tabloids heralded them as “it girls” who sashayed across the streets of Swinging London and right onto the glossy pages of Vogue. Alongside one photo of Springfield, an article read: “Dusty has long been one of London’s top trendsetters. In fact, every other girl in the UK has ‘Dusty Springfield eyes’, which means they wear lots of carefully applied black, black eye make-up. It takes Dusty 30 minutes each morning to put hers on!”

“There was a story in the local paper saying Woolworth’s ran out of black mascara, because they all wanted the Dusty Springfield ‘panda’ look,” says British photographer Ian Wright, who captured the invaders throughout the Sixties. Before the ink could dry, the trend had taken off in the US, too. Everything from their hairpins to their lace stockings became public interest. Beyond these controlled images, however, Wright describes the performers as always kind, open and generous. “[Cilla’s] door was open. The kettle was on,” he explains.

Shaw’s then-controversial preference for performing sans shoes was more than just a fashion statement, too. An excerpt from her book The World at My Feet explains: “It is more comfortable – I could never find shoes to fit my size seven-and-a-half’s in Dagenham. It is one less thing to think about when getting an outfit together.” Shaw had the confidence to take the stage and steal the show while refusing to conform to beauty standards. “Sandie doesn’t give a f***,” laughs Rumer about Shaw’s bold, sharp wit and attitude. “That’s what I love about her. She says things I would never have the balls to say. She’s one of my favourite people.”

It wasn’t easy being a woman at the front of the British Invasion. They took controversy in their stride and handled criticism with a certain grace. During that time especially, the press were notorious for concocting fictional feuds between the British pop singers, often attempting to pit the women against one another. Black wrote in her 2003 memoir, What’s It All About?: “The press were always making out that we were huge rivals who didn’t get along, but because we were all so different, we were actually all good mates.”

That misogyny and sexism is most likely a crucial factor in why these women don’t get the same credit as their male peers. “I don’t think they did anything different to what the chaps did, whether they were groups or solo singers,” says Wright, though he attributes the discrepancy in the amount of female successes to homesickness and culture shock. When their careers took off in the States, singers such as Black, Shaw, and Faithfull were still growing up, facing fledgling fame in their teens and early twenties. “This, for some of them, was the first time they’d ever left England,” Wright says, “So it was a huge culture shock to most of them.”

Being immediately launched onto the stages of New York and Las Vegas was a far cry from the nightclubs and dance halls of Britain, he says. “They held their own. They contributed with all these great songs.” It was especially challenging for Clark, who was juggling a successful career and family life. By the time America came calling, she had not only established her career across Europe, but she was also a wife and a mother of two. “It just took me on a journey that I wasn’t expecting to take,” she says of her success in the States. While she admits things could get complicated, she says: “It was a very special time in my life because I was trying to balance my family life, a career, not only in America, but in Europe too.”

The arrival of the British Invasion brought about a cultural tipping point in America, especially for women in music. The solo female singer was finally in the spotlight. Today, after several iterations of very female-centric British Invasions (in the Eighties with Bonnie Tyler and The Eurythmics; in the Nineties with the Spices Girls; and onwards, with Amy Winehouse, Leona Lewis, and Adele) the female British solo vocalist continues to make comeback after comeback because of those who paved the way. So as critics and fans continue to delve into Peter Jackson’s epic seven-hour documentary on The Beatles, it’s a relief to know that the women of the Brit Pack, like Dusty and Marianne are finally getting their dues, too. Will the films do them justice? Here’s wishin’ and hopin’.

Read More

Peter Jackson on The Beatles and Get Back: ‘I get the feeling now that history has arrived’

‘Not a single security guard helped me’: The urgent need to make gigs and festivals safer for women

Anarchy in the UK: How the Sex Pistols’ snarling manifesto changed the face of punk

The 30 greatest album covers, ranked

Here comes the shun: The current flavour of Beatles-bashing is as lazy as it gets

Peter Jackson on The Beatles and Get Back: ‘I get the feeling history has arrived’

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance