What Makes Rolex So Special?

Last November, in the misty Before Times when people could still share physical space with one another, a ballroom in an exclusive midtown Manhattan hotel welcomed 110 apex watch collectors from 13 countries for cocktails, lunch and a “sexpile”.

Before your head fills with Bret Easton Ellis images of moneyed debauchery, be aware that the “sexpile” is composed not of human bodies but of watches: hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of vintage Rolexes, piled atop one another like mating crabs. In a room disguised as a “Real Estate Investors’ Convention”, rare Submariners and Cosmographs, Day-Dates and Milgausses, Oysters and Daytonas littered the tables, ostentatiously jewelled, simply understated or — as aficionados love them best — weathered and faded to a “tropicalisation” unique to each piece, an organic process which speaks of travel, extremes of temperature and untold stories.

This was America’s first Rolliefest, an $850-a-ticket, invitation-only gathering of some of the world’s most influential watch collectors, an event which grew out of an exclusive online community of Rolex-worshippers. Among the pieces on show was a solid gold Daytona formerly owned by the Sultan of Oman and known as the “Red Sultan”, and a 1958 Rolex GMT-Master Ref 6542 whose original radium lume still registered a hazardous 99.9 microSieverts (yes, one Rolliefest attendee brought along a Geiger counter).

And the centrepiece was the “sexpile”: some of the world’s rarest and most valuable watches strewn haphazardly along an 18ft table for Rolliefest attendees to handle, examine and wear. With an estimated $50m–$100m worth of timepieces in the room, this amounts to either an admirable display of faith in the code of the Rolex-lover, or a nerve-shredding invitation for something to go missing. Perhaps the armed guards on the door lent an air of confidence.

“The thing about the Rolliefest,” Dutch watch entrepreneur and attendee Bernhard Bulang will tell me later, “is that it’s not about money. It’s about meeting the people and being inspired. This is a community.” Then again, the chance to examine exquisitely rare grail watches up close is not to be sniffed at. “You know, you can’t use a loupe on Instagram…”

A designer by profession, Bulang was a latecomer to the Rolex Illuminati. He only began collecting when he was 35, transferring his love of modern furniture design and his father’s obsession with collecting vintage postal memorabilia — “You would discover crazy stuff! War correspondence! How the Russian tsars got their Champagne through secret channels!” — over to the world of watches. He had never really wanted to collect Rolex (“I thought they were only for the Italian bling-bling guy”) and after a trip into the Maastricht shop of Philipp Stahl, who would become a good friend, he’d bought an IWC Aquatimer instead. But the 5530 Rolex Submariner that Stahl had shown him kept “itching like crazy”. Within days he went back and bought his first Rolex, a small crown James Bond. “And then it started. I think I bought another Rolex once or twice a week from then. I went frantic.”

He’s now 51 and he’s making up for lost time by running the Bulang & Sons concept store close to Maastricht in the Netherlands. It sells watches, own-brand high-end watch straps, watch-related style and curated packages of Rolex-adjacent goods, like a bike designed to complement the legendary Red Submariner. “We like to bring out the soul of the watch,” he says. “All the furniture I loved, like the Eames chair, was designed in the Fifties and so were those Rolex watches. Something special happened in that period, something was perfected, and they are still relevant today.”

And what exactly is that? What makes Rolex so singular among watch brands? “Let’s be honest,” he says, “Everyone who puts on a Rolex knows it’s a sign of success. But really it should be a sense of achievement for yourself. Sure, there are people who buy Rolex to show off, but most people would not know if you were wearing a $150,000 watch. It’s not for them, it’s for you. You can wear a Newman anywhere and nobody would know what it means — except you.”

There are the totemic associations, of course — the graduation, wedding or promotion gifts — and the stories unique to each watch. These, as we’ll see, were tool watches for professionals. But for Bernhard Bulang the attraction is simple. It’s a classic. “Rolex is not like other brands with endless complications and embellishments,” he says. “They are simple but the perfection is incredible. Rolex is more like a giant tanker that doesn’t change course. They don’t need to chase novelty. They get the biggest respect from me for keeping their own course.”

In the 2000s, Bernhard and Philipp Stahl co-organised the Rolex Passion Meetings, the precursors to Rolliefest, as a way to bring online forum obsessives together. The first was in a little chateau near his place in the southern Netherlands. “It wasn’t the big shots,” he says. “It was about the people with the right mojo and the right passion.”

At the earliest events there would be maybe $20m on the table “and zero security. Now it’s maybe $60m”. He remembers taking the Rolex collectors into Maastricht for a Friday night, and the bread bucket on the table of a packed bar was filled with MilSubs. One guy left $2m–$3m of watches in a box on the table and went to eat while his fellow collectors tried them on.

“I mean, it was childish and crazy,” says Bulang, “But that was the magic of the meeting. It’s friends. And,” he adds, “There was never a watch lost."

Rolex is a religion. There are more costly watches. There are rarer watches. There are watches with finer complications and more intricate movements and more esoteric brand positioning. But none of them has managed to combine exclusivity with global ubiquity like the company founded in London as Wilsdorf and Davis in 1905 and renamed Rolex in 1908 (they’ve been in Geneva since the end of WWI but yes, at a stretch you could say Rolex is a British company).

“If Rolex is a car, it’s a Porsche,” says the maverick watch dealer Tom Bolt: remember the name, we’ll be meeting him again later. “They’ve pulled off this combination of mass market and true high end. They’re luxury, yes, but they’re not unattainable.” Rolex means status means achievement means power means success, but you don’t have to be a CEO (yet) to get there. Around £2,500–£3,000 will buy you an entry-level, 21st-century Oyster Perpetual, and then you are on your way, with the bonus that any Rolex tends not to depreciate in value. “And they’re still very good value for money,” adds Bolt. “Their movements, for the money, are fucking great value. For the price point there is nothing like them. It’s affordable excellence.”

It is also meaning. Rolex means manhood, means role models. Few watch brands are scattered through sports, literature and pop culture as liberally as the Rolex. When Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing conquered Mt Everest in 1953, they wore Oyster Perpetuals on their wrists; Jacques Cousteau conspicuously wore a Submariner, the first diver’s watch, throughout a career that brought otherworldly visions of the ocean floor into cinemas and homes for the first time. Winston Churchill and Martin Luther King both wore gold Datejusts (Churchill’s was the 100,000th Rolex produced) as did Mao Zedong, who owned two. Fidel Castro wore a GMT and a Submariner at the same time; legend says he wanted keep track of time in Moscow and Havana as well as Washington. Marilyn Monroe gave John F Kennedy a gold Day-Date as a birthday present: for reasons you can imagine, Kennedy never wore it.

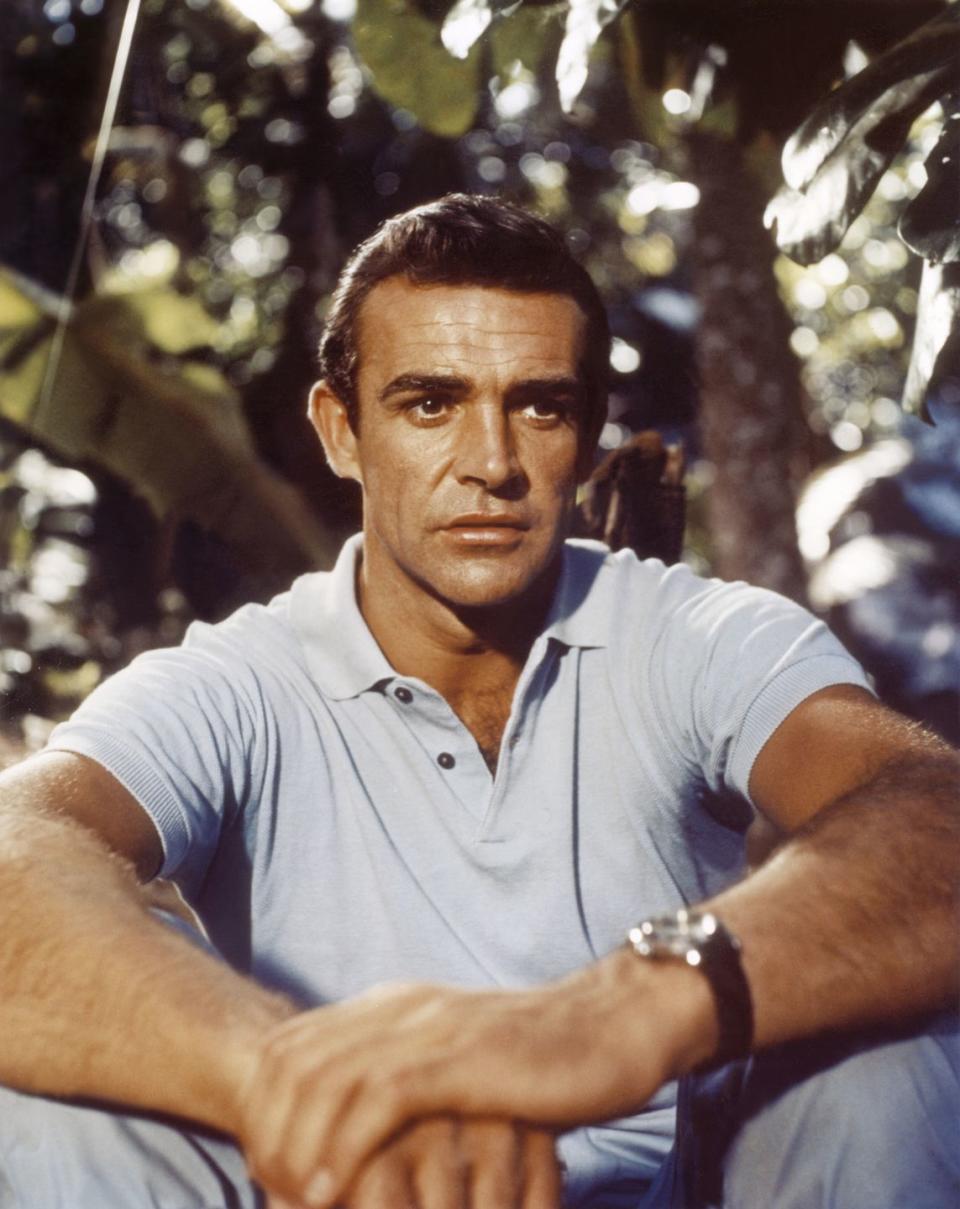

In fiction and entertainment, Rolex is almost a character in its own right. Ian Fleming famously wrote James Bond as a Rolex-wearer, identifying the model as an Oyster Perpetual late in the day, in the 1963 book On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (Bond uses it as a knuckle-duster). Bond’s life in the movies began in 1963 with Sean Connery wearing producer Cubby Broccoli’s Submariner Ref 6538 in Dr No. Rolex had declined lend the film-makers a watch, as product placement was yet to be imagined. Thus was the “Bond watch” born.

Elsewhere, Paul Newman’s association with Rolex and race-car driving was so intense that his own 1968 Daytona — presented to him by his wife Joanne Woodward during the filming of Winning and inscribed “Drive carefully, Me” — would sell at auction for $17,752,500 in 2017 and become the most expensive watch in history. And it’s not always the good guys. Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now? That’s a Ref 1675 Rolex GMT-Master. Alec Baldwin as arch-bastard Blake (“Always be closing”) in the film version of Glengarry Glen Ross? A Day-Date, inevitably. And Christian Bale as Patrick Bateman in American Psycho? A Datejust, the Wall Street watch, in steel and gold. The company insisted Bateman not be seen wearing it while committing any heinous or distasteful acts, so blink and you’ll miss it.

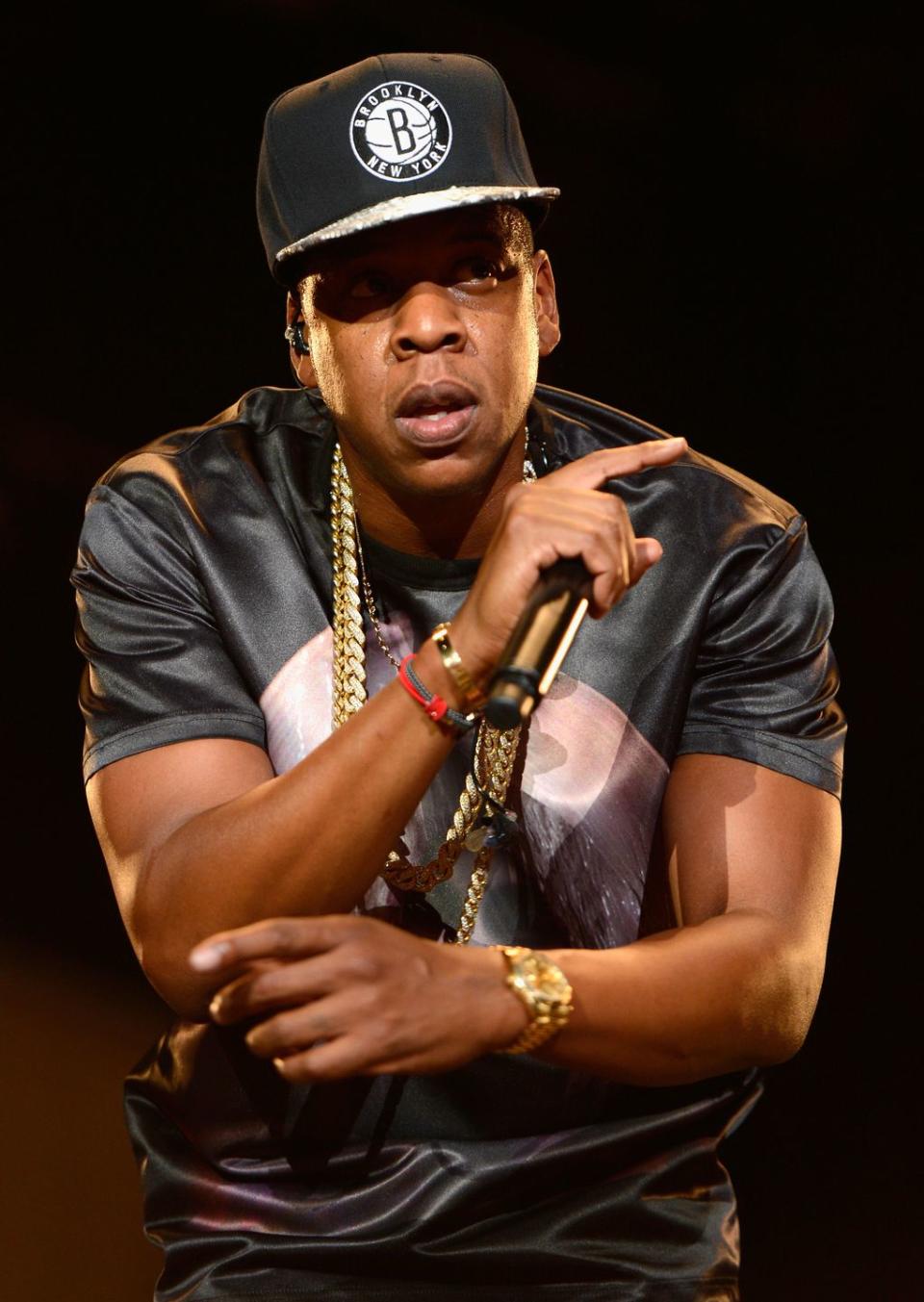

But all of this would be in the past if Rolex had not also become the beneficiary of the most powerful social force on the planet. Rolex is by some distance hip-hop’s favourite watch, the signifier of status in this most status-conscious of music cultures. Yes, there are hip-hop stars with a taste for the wilder reaches of horology: Pharrell with his science fiction Richard Mille RM 031High Performance, or Rick Ross’s diamond-encrusted Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore. But on the numbers and the namechecks, Rolex wins hands down.

Drake owns rare Yacht-Masters, GMT-Masters, Daytonas and even the unusual Oysterquartz, Rolex’s sole experiment with non-mechanical movement. Eminem’s Datejust was practically a part of his brand, and in what you have to hope is not a portent of the electoral future, Kanye West’s extensive collection includes a gold Day-Date II President. Jay-Z, among the most cultured of watch collectors, wore a platinum Day-Date on the cover of the In My Lifetime, Vol 1 album and is regularly seen with a Rolex. And in UK grime, the infatuation with the big crown brand extends beyond Wiley’s 'Wearing My Rolex', still the only UK top ten hit to celebrate a watch brand; Stormzy and Dave have both used Rolex as totems in their stories of success against the odds.

The reasons are not hard to parse; they are both personal and political. Back in 2003, a University of Southern Denmark study entitled 'Bling Bling — The Economic Discourses of Hip-Hop' argued that the genre’s love affair with status symbols “presents us with a case where economic language is used in a positive, affirming way… by a subculture that is usually seen as repressed and downtrodden by the very capitalism it celebrates”. The subsuming of predominantly white, C-suite culture into the world of the streets tells its own story about struggle and achievement.

In other words, we were on the outside. Next thing, we’re wearing your Rolex.

Every religion needs its bible. While there have been many books published about the history and meaning of Rolex it’s doubtful if they can approach the scope and depth of Vintage Rolex: The Largest Collection in The World, a gorgeously indulgent new coffee-table heavyweight by David Silver, director of London’s Vintage Watch Company, which has just been published. David, an affable and enthusiastic Londoner, joined his father John to open the landmark watch store in Burlington Arcade off Piccadilly, the capital’s Diagon Alley of luxury goods, in 2005. Learning from his father’s retail experience at Debenhams they quickly phased out other brands to focus on Rolex.

“We needed critical mass,” David Silver explains, “so our critical mass would be, we’ll build the largest collection of vintage Rolexes in the world.” Along the way VWC made themselves synonymous with the birth year watch: Kate Moss, Gordon Ramsay and Bill Clinton are among the customers who have bought friends, colleagues and fellow dignitaries a Rolex made the year they were born. VWC’s knowledge and connections are such that they have on occasion sold rare Rolexes to Rolex, for their company museum.

As one of the earliest watch dealers to operate a comprehensive website, VWC had every piece professionally photographed, in forensic detail, using the same photographers, Bruce Mackie and Charlie Sawyer, for 25 years. “So we found ourselves with a unique 25-year archive of watches that are impossible to bring together again,” says Silver. “We were always wondering what we should do with it. So we thought we’d showcase it as a book.”

The result is almost 400 pages of sumptuous, all-out Rolex porn, a detailed piece-by-piece chronology of horology from the brand’s earliest days — lots of square cases, art deco typography and only the ghosts of Rolexes yet to come — via the genesis of the utilitarian sports watches in the Forties and Fifties, to the dazzling colours and iced-out madness of the Seventies, when Middle Eastern money flooded into the watch market and Rolex’s “Crown Collection” began to cater to tastes somewhat more lurid than its original customers in the uptight West. On the cover there’s a 1989 Oyster Day-Date with a yellow lacquer dial known as “Stella”, of a type which recently fetched £170,000 at auction; inside there are over 1,800 Rolexes organised by model, style and evolution. As well as a work of reference, with a detailed glossary, it’s a sexpile on paper. And the extreme detail of the photography brings out subtle changes and evolutions even to the watch neophyte. You might not be able to use a loupe on Instagram but you very nearly can here.

“There’s a bit of pride in being to stand back and show the watches we’ve handled over these years,” says Silver. “What I like about the book is that it’s a history of the world through this watch [brand]. You see how society, fame, celebrity and aspiration develop over the decades. You can see the decadence of the deco period, WWI watches and then the buzz of the 1920s. You see the background of sport and exploration, the race to be the first to achieve these things — Rolex was ahead of the game on everything.”

One of the book’s standout spreads comes from the opulent, oil-driven years that Silver calls “Stella and Stone”. It features a presentation box of 15 such extreme luxury watches, with dials in bright green, ocean blue, orange, and a staggeringly decadent ruby, sapphire and diamond coral effect. The statement of these watches is not just money but also power, and its shift eastwards as economics refashioned not just the world of geopolitics but Rolex’s own aesthetics.

“What’s extraordinary is, not only did we have all these watches at VWC but we had them at the same time,” says Silver. “That box is not photoshopped. It’s real. And we sold it as a complete set for £1m. That collection is impossible to replicate now.” And what would it go for now? “Several million, easily.”

What the book makes clear is that Rolex wasn’t always Rolex. From its foundation in Hatton Garden in 1908 by German emigré Hans Wilsdorf and his English brother-in-law Alfred Davis, through its tax-driven relocation to Geneva in 1919 and on to the Thirties, a Rolex watch seldom resembled the indefatigable power-piece we’re familiar with today. Or indeed did the same job.

“The moment that changes everything for Rolex is 1926,” says Silver. “The birth of the first Oyster, the first waterproof watch. That is the turning point. Very early on in their life as a company, they create something monumental.” A true waterproof watch was the grail of Twenties horology and the arrival of the Rolex Oyster came with a story that’s surely worthy of a movie in its own right.

On 7 October 1929, Mercedes Gleitze, an amateur swimmer from London, became the first Englishwoman and only the 12th person ever to swim the English Channel. It took her 15 hours and 15 minutes, after which she collapsed unconscious, but Gleitze’s moment of glory was quickly tarnished when a woman called Mona McLennan claimed to have achieved the same feat in just 13 hours and 10 minutes. Although McLennan was quickly exposed as a fantasist, Gleitze felt obliged to remove all doubts and scheduled a “Vindication Swim” for 21 October. Wilsdorf, spotting an opportunity to publicise his new waterproof watch, sent her a gold Oyster to time her swim and clear her name.

Although Gleitze failed to complete the distance on this second attempt — sea conditions in late October were described as “brutal” — the character and fortitude that she displayed convinced all witnesses that her original record attempt had indeed been genuine. Wilsdorf, meanwhile, took full advantage of the event with a front page advertisement in the Daily Mail proclaiming “the greatest triumph in Watch-making” (sic). Sports connections would prove integral to the Rolex brand in decades to come, and Gleitze would feature in advertising well into the 21st century. (For the VWC book, Silver managed to get hold of Mercedes Gleitze’s daughter, who supplied unseen images and more detail on her story. “One fact we uncovered is that she never actually wore the watch on her wrist,” he says. “She wore it on a rope around her neck…”) The hands of all subsequent Rolex sports watches are known as Mercedes Hands; everyone assumes they’re named after the car, but they’re named after the swimmer. With this first sporting association, the Oyster was on its way. So was Rolex.

There are other moments when Rolex further evolves into the Rolex we know. There’s 1953 and the original Submariner, the first diver’s watch with the unmistakable and much-imitated rotating bezel for timing your dive, waterproof to 100ft. There’s 1956 and the arrival of the Day-Date, the original President’s watch, the first watch to display the day in word form as well as the date. “That’s when heavy gold and the concept of prestige come in,” says Silver. “If you’d made money and you wanted to show it, if you wanted recognition on your wrist, then you went for a Day-Date.”

So, the Wall Street watch of the Eighties was actually born in the Fifties. “This is when Rolexes start to look like a real family of watches, when the things that Rolex lovers will obsess over start to come in.”

And this is also when the fictional creation of a former naval intelligence officer is taking shape as a new kind of hero, both a representative of Britain’s fading imperial powers and of a future where good taste in haute brands would become synonymous with manhood. Debuting in Casino Royale in 1953, James Bond would become the avatar of a new internationalism in luxury brands. On his wrist: the Rolex Oyster Perpetual.

In the early 2000s, Tom Bolt — a self-taught Rolex obsessive and a highly entertaining character on the Rolex scene, as we’ll discover — was approached by a dealer for an opinion a watch that (he was told) belonged to “the real James Bond”. Bolt’s contact had been offered a particular Sea-Dweller for around £16,000 that was a little… odd. The Sea-Dweller is a diver’s watch with an innovative gas escape valve, enabling controlled de-pressurisation so that, unlike lesser pieces, it won’t explode upon resurfacing. This one was more unusual still.

“It turns out that this was the very first Rolex wristwatch ever made to incorporate that new gas escape valve,” explains Bolt, a lively, incorrigible raconteur whose love of Rolex is infectious. Here was the fabled Single Red Sea-Dweller, the original prototype with the rare 500m denomination and Sea-Dweller in red on the dial (hence the name). In 2017, it was estimated that there were no more than 20 still in existence, of which only five or six have the gas escape valve, an innovation added after the first flawed production run in 1967. The watch offered to Bolt was the very first of the gas valve Sea-Dwellers. And that’s when it got interesting.

“This watch,” says Bolt, “was made for a man called Dr Ralph Werner Brauer, who wasn’t just an accomplished diver, he was a CIA operative.” Bolt describes Brauer as an Indiana Jones figure, a “genius mind” and teacher who fled Germany during WWII, began working for the US defence establishment, orchestrated world-record dives and was instrumental in the development of mixed-gas breathing for extreme depth dives. In 1978, at the height of the Cold War, Brauer was admitted into the USSR for research in Siberia’s Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest body of fresh water located in southern Siberia. Brauer’s assistant later told Bolt that the doctor would surreptitiously question off-guard Soviets and take photos with a micro-camera. When Brauer died unexpectedly in 2000, his Single Red Sea-Dweller was found hidden under a mattress, along with money and a gun.

“So not only was Ian Fleming’s fictional James Bond kind of the original Rolex guy,” says Bolt, “but this watch belonged to a man who basically was James Bond.” Brauer’s Single Red sold for around £40,000 on the original deal. Bolt recently bought it back for £500,000.

It was Bond who ignited Bolt’s interest in Rolex when Bolt was a child. After he saw Live And Let Die, he pestered his parents, the actress Sarah Miles and Oscar-winning screenwriter Robert Bolt, for a watch, yet the Timex they bought him wasn’t quite right. For a start, it didn’t have an electric saw in the bezel. The fascination with Rolex grew and grew; after all, his father wore Rolex and so did the legions of movie stars who passed through the family home. After a chaotic childhood and teens — “18 different houses, 12 different schools, living in Hollywood as a kid, drink, drugs, bands…” — he credits a growing obsession with Rolex with his salvation.

“I haven’t had a drink in 33 years now,” he says, “and Rolex is hugely instrumental in giving me a passion and a focus that allowed me to turn my life around. My addictive nature was able to morph from the negative to the positive. And now I have the most amazing lifestyle that I couldn’t have dreamt of as a kid.”

Bolt bought his first Rolex at 19, when he’d run out of road and was working in a warehouse and cleaning houses for a living. He found a second-hand Air King for £300, then had to sell it, but he made £35 on the deal. “And the rest is history.” Unable to open a bank account (“I’d been blacklisted for being a naughty boy”) he raised £1,500 from a loan shark and dived into a vintage watch market which was surprisingly undeveloped. “Back in the late Eighties, a Rolex Moonphase in steel was a £15,000 watch,” he says. "Now it’s a million-and-a-half. I could afford to make mistakes back then. Yes, there were fakes but you wouldn’t lose your shirt. Now, if you haven’t earned your stripes already it’s much harder to do it.”

What does he think is the secret of this brand’s juggernaut success? “It’s a mix of things. Yes, they’re relentless in their advertising. Yes, they have loads of firsts to their name: the first wrist chronometer; the first waterproof watch; the first self-winding automatic watch. These are all massive things.

“But there is one very, very big thing that Rolex did,” he emphasises. “They didn’t lose their nerve in the late Sixties, early Seventies when the big watchmakers faced that double whammy of the quartz movement, which told time better than any mechanical watch ever could, and the Japanese mechanical watches.

“Everybody panics. It’s the end of the world. You have customers wondering why should I buy a £400 watch when I can get a three-quid quartz watch that tells better time? Everybody goes crazy. Omega panicked and did watches for the masses, lowered the price point. But Rolex just steam on through it. They brought out one Quartz watch, and they just sailed through the other side and galvanised themselves even more in glory. That’s what did it. They just had the balls to keep going.” (Ironically, he says, the Oysterquartz is now quite collectable, especially after Rolex incorporated their own “very expensive, very high-tech” quartz movement. Hey, Drake’s got one.)

The Rolex is iconic, he thinks, for the same reason that a Porsche 911 remains iconic. You go back through the decades, it’s the same car. The bonnet, the tail and the lights have changed but it’s a Porsche 911. “And a Rolex Oyster, from the Bubbleback in the Thirties to now, is the same watch today. If you avoid the minutiae of obscure detail, all that Bart Simpson crown stuff, and just buy a pure Rolex sports watch from the Sixties, Seventies or Eighties then you cannot lose money.”

Bolt has his issues with contemporary Rolexes and their perhaps over-refined computer-aided design. “The originals have soul. The moral is, if you’ve got a great design, don’t fuck it up.” But at its core, a Rolex is a Rolex is a Rolex.

And in a full ‘Rosebud’ turn of events, in the early Aughts, Tom Bolt found himself owning the original Live And Let Die Rolex, the one that ignited his love of the brand in the first place. He bought the prop watch, a modified 1972 Submariner Ref 5513, from Christie’s for £35,000, complete with the original drawings from prop designer Syd Cain. The saw was still in its bezel and Cain had replaced the movement with a custom rotor which made the saw spin with compressed air. Bolt set to work on it and converted it back into a working watch, then took Roger Moore out for lunch and got him to sign the back, with an agreement that Bolt would make a donation to Unicef (he did). “We had a great conversation,” Bolt reminisces. “Turned out he actually knew my parents anyway…”

Wait, there’s more. Bolt then traded the watch for a 1967 Ford Mustang Shelby GT500. And bought the watch back. And sold it again. “My business model is selling the same watch on average three times,” he says. “With Rolex, if you buy good pieces they are an appreciating asset.” Eventually, the Bond Rolex last went at auction for around £300,000 and I wouldn’t bet against it passing through Tom Bolt’s hands again one day.

Is there any watch he couldn’t sell, I ask? Bolt laughs. “The only watch I would not sell, for which there is no price,” he says,” is the Rolex Air King Date that belonged to my father. I mean, what kind of man would I be if I sold my dad’s Rolex?”

It’s mid-August this year. The shops are finally, tentatively reopening. I visit David Silver at the Vintage Watch Company in Burlington Arcade off Piccadilly. The bustle is undeniably less than what once was, but there are people about. And the VWC window is open again, a chronological panopticon of a century of watchmaking — an historical tableau, a free Rolex museum. “People always say, what’s the rarest watch in the window?” Silver says. “I tell them, well what’s the watch that you like? What’s the one that connects to you?”

He talks me through the display. There are the very rare 1958 and 1962 James Bonds on Nato straps, tropicalised and chipped on the bezel, yours for £40,000–£45,000. God knows what stories these pieces have. There’s the first Explorer from 1953: the Mt Everest watch. There are 20-plus blue-and-red Pepsi GMT-Masters, and the black-and-red Cokes. There’s a GMT personalised to the Hollywood special effects designer Milt Rice, who worked on The Magnificent Seven and Some Like it Hot among a host of classics (this very watch may well have told Marilyn Monroe she was late on top of that ventilation grate). There are pre-Newman Daytonas and WWI officers’ watches and the wild psychedelia of the Middle East-aimed Crown Collection with its malachite and lapis lazuli and diamond bracelets. “It’s a bit of a something-for-everyone window,” he says drily. Yes, and then some.

Inside the shop, he hands me two of the most opulent Crown Collection watches. One 1995 white gold Oyster Day-Date has diamond bezels and lugs, a diamond dial and black sapphire markers; at £143,750, it’s got BET Hip-Hop Awards written all over it. Another Day-Date, this one in 18k yellow gold with diamond bezel, black dial with diamonds and diamond shoulders, is a snip at £99,000. They are lavish and ostentatious, true statements of money and power, but these are not ugly watches. This is Rolex craftsmanship, and you can tell the difference between this and the blinged-out aftermarket work you might see on MTV. “You can always tell aftermarket,” says Silver cheerfully. “The quality of work is shit…” But I’m hardly listening, because four times the original value of my flat it is nestled in my trembling palm. That’s Rolex. The foothills are attainable but the peaks are in the misty distance.

Then again, you might get lucky. Some years ago, an elderly lady turned up at VWC with lots of Sainsbury’s grocery bags which she began to unpack on the counter. “It was basic watch after basic watch, like pass the parcel,” says David. He was about to say, in the kindest way, that these were not really our thing when she unwrapped another package. It was a Submariner, English naval officer issue, the rarest edition with an Explorer dial and a 3, 6 and 9 on the face. “She needed a cup of tea and a sit down after we offered her the value,” says Silver. This watch now fetches around £100,000. So keep an eye out. You may be the one who could wear the crown.

This article is taken from the Big Watch Book 2020, available now

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance