KY kept paying a dead man for four years. Then it billed his daughter for $56,920.

Glen Vernon Coleman Sr., a retired Pike County coal miner, died March 25, 2016, at age 73. His family notified the usual authorities and buried him in a Pikeville cemetery. But the state of Kentucky continued paying the dead man’s workers’ compensation benefits — $555 every two weeks — for the next four years.

The state finally realized its mistake in 2020. It sent Labor Cabinet special investigator Amy Thurman to seek out Coleman’s next of kin. Did they know what happened to the $56,920 in “over-payments”? The state wanted that back now.

Thurman learned the money had gone into a bank account Coleman shared with one of his daughters, Kimberly Rhodus, who had many bills to pay and no idea, she told Thurman, that it wasn’t hers to spend. When the cash just kept coming, Rhodus said, she figured it was meant for the family, like her father’s life insurance policies.

“I am assuming that maybe it is some kind of survivors’ benefits,” Rhodus told Thurman during a recorded interview last June in her Section 8 low-income rental housing in Richmond. “Because surely to God if he had passed away and that was money he shouldn’t get, it would stop, you know?”

“You would think,” Thurman replied.

Rhodus was a substitute teacher who had no work during the COVID-19 shutdown, with several children. The state told her to choose between a prison sentence of up to 10 years for felony theft or a court-supervised, $500 monthly repayment plan over the next decade that she cannot afford. She chose the latter.

“I’m like, ‘I don’t want to go to jail! Whatever will keep me out of jail, I’ll do it,’” Rhodus told the Herald-Leader this week. “For the life of me, I still don’t understand what happened here — why they were paying us money for four years and now they’re saying it was all a mistake — but I do not want to go to jail over it.”

Glen Coleman’s daughter wasn’t the only one in such a predicament.

The small state agency that runs the workers’ compensation Special Fund — which provides $42 million a year to about 4,100 people — was so badly broken that it failed to notice the deaths of several hundred beneficiaries. As a result, it was sending out more than $860,000 in benefits payments that should have been canceled.

Among other examples:

▪ Danny E. Ratliff died March 28, 2019, in Pike County. The Special Fund kept paying him for 21 more months, to the sum of $13,106.

▪ Benjamin “Gene” Daugherty died Jan. 13, 2015, in Louisville. The Special Fund kept paying him for five more years, to the sum of $16,462.

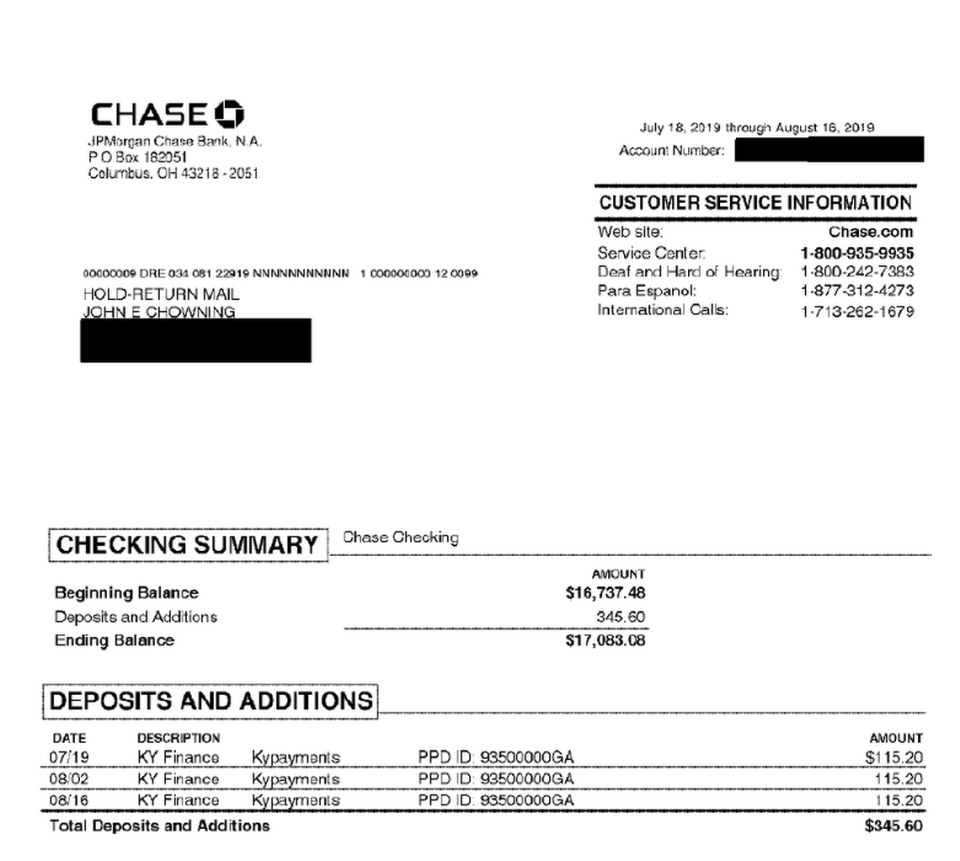

▪ John E. Chowning died Nov. 8, 2013, in Lexington. The Special Fund kept paying him for seven more years, to the sum of $19,732.

▪ Paul E. Mosby died March 25, 2014, in Metcalfe County. The Special Fund kept paying him for five more years, to the sum of $57,025.

As cases are identified, the dead beneficiaries’ elderly widows or grown children get letters from the Special Fund offering belated condolences and announcing that “money paid after the date of death” is due in the next 60 days, so please send a check or money order for the full amount to the Kentucky State Treasurer.

By then, the dead man’s estate could be closed in probate court, and his heirs might have settled his affairs — or so they mistakenly believe.

“This would be difficult for a family to process, to say the least,” said Larry Brown, a Prestonsburg lawyer who is helping relatives of Ratliff to administer his estate.

“Surely to goodness, once an estate is closed, you don’t expect the relatives to pay for this personally out of their own pockets, especially if the state made the mistake and is just now figuring it out,” Brown said.

Sometimes the over-payments are sitting in a dormant bank account where the Labor Cabinet easily can retrieve them. Other times, the state has convinced prosecutors to bring felony theft charges against the children and grandchildren of beneficiaries, arguing that they spent money they should have realized was supposed to be returned to Frankfort. Four of eight known defendants in these cases have been convicted so far.

The total of Special Fund “over-payments” keeps growing over time as more mistakes are uncovered.

The Labor Cabinet said in a prepared statement that it has recovered $574,194 so far. An additional $290,000 has been identified as outstanding, cabinet officials say, although only $223,000 of that is considered to be “potentially recoverable,” cabinet officials said this week.

The fumbling of Kentucky’s Special Fund bridges the administrations of former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin, who left office in December 2019, and current Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear.

“There were a lot of irregularities that I became aware of,” said attorney Judith Ann Erickson, one of several Special Fund directors to rotate through the agency in recent years. Erickson served for just seven months during the Bevin Administration.

“There were issues going on even before Bevin that I was trying to bring to everyone’s attention,” Erickson said. “And then I was summarily discharged.”

The Labor Cabinet’s Office of Inspector General last year laid much of the blame on constant turnover and turmoil within the Kentucky Department of Workers’ Claims, which runs the Special Fund. Nobody knew what was going on at the agency because nobody stayed around long enough to master the operations.

“Over the past three years, the Special Fund had three different directors as well as an assistant director detailed to the director’s position,” Inspector General Michael Wright wrote in February 2020.

“During Fiscal Years 2018-19, all Special Fund employees either retired, tendered their resignation or transferred to other state positions outside the Labor Cabinet, creating a void of leadership, experience and historical knowledge,” Wright wrote.

The Beshear Administration’s current commissioner of workers’ claims, Robert Swisher, declined to be interviewed for this story.

‘Good enough ... get the checks out’

Workers’ compensation helps cover the lost wages of people who get hurt on the job. Employers in Kentucky typically purchase workers’ comp coverage from the marketplace, often from a state-chartered agency known as Kentucky Employers’ Mutual Insurance.

However, by an act of the General Assembly, older workers’ comp claims from on or before Dec. 12, 1996, were consolidated into the Labor Cabinet’s Special Fund. The pool of beneficiaries in the Special Fund is shrinking over time as the claimants age and die.

Money in the Special Fund comes from an assessment levied on workers’ comp insurance premiums collected by insurance carriers and simulated premiums calculated by self-insured employers. The rate jumped to 7.02 percent this year, up from 6.41 percent, the highest it’s been since 2005.

For most of the Special Fund’s current incarnation, starting in the late 1990s, its director was a Labor Cabinet attorney named Robert Whittaker. According to several interviews with past Labor Cabinet officials, Whittaker ran the agency as his own fiefdom inside the state bureaucracy until his unexpected death in November 2016.

It was difficult for anyone to step into the vacuum left behind by Whittaker, said state Sen. Mike Nemes, R-Shepherdsville, who served for a time as Bevin’s deputy labor secretary and, briefly, labor secretary.

“He’d been there for years, and it was a mess,” Nemes said. “Nobody knew what anyone else was doing.”

“The Special Fund was like a dark secret. Nobody at the cabinet knew what they did, so everyone spoke of it in hushed tones,” said Robert Milligan, a retired Kentucky State Police lieutenant colonel who was one of the several directors assigned to a stint running the Special Fund after Whittaker died.

“From a management standpoint, they just left them alone. As long as people were getting paid, management said, ‘OK, good enough,’” Milligan said. “The main priority was, ‘Get the checks out, get these people paid.’ Because when you don’t, the calls come in. That’s when people complain.”

‘That check was a lot of money’

In 2018, the Labor Cabinet’s inspector general was told to investigate a tip that someone was stealing from the Special Fund. That allegation proved untrue — Milligan said it was just a squabble between two employees — but another problem was identified: The Special Fund was paying dead people.

Milligan said a simple Google search of beneficiaries’ names on some returned checks piling up in the Special Fund offices led to online obituaries.

“We were finding people who had been deceased, and some of them had been deceased for quite a while,” Milligan said.

The Special Fund was supposed to know when beneficiaries died. Employees were trained to check a variety of sources, including the Social Security Death Index, to see if any names in its Claims Payment Management System matched the recently deceased and needed to be removed.

But not long after Whittaker died, the Bevin Administration transferred the Special Fund to a different division within the Labor Cabinet and physically moved its offices to a different building in Frankfort. In the months that followed, as several new directors came and went, all of the Special Fund’s employees departed.

“That exodus left the Fund with a critical staffing shortage that the Labor Cabinet is now aggressively addressing. The loss of institutional knowledge regarding the processes and procedures of the Special Fund has proven to be a particular challenge,” inspector general Michael Wright wrote in a February 2020 report.

The Special Fund was audited annually. But the auditors only requested “80-plus files at random to review,” so unless they happened to pull the file of a dead beneficiary, the problem was missed, according to an inspector general’s report in September 2020.

Milligan, who ran the Special Fund for 2019 and early 2020, said he tried to enact reforms. He mailed forms to beneficiaries to verify they were still alive. He arranged for the Special Fund to check death data at the Kentucky Office of Vital Certificates.

More than 300 dead people were identified in the Special Fund’s database. At least 60 of those accounts showed “over-payment” balances totaling a cumulative $562,573, the inspector general wrote in early 2020.

Some beneficiaries’ relatives kept accepting the biweekly payments, whether or not they understood why they were getting them.

“To a lot of families in Kentucky, that check was a lot of money and they felt entitled to it,” Milligan said. “Even if Pa was dead, the kids wanted to find some way to keep collecting it.”

Also, the rules on survivors’ benefits are poorly understood, he added. Spouses may keep receiving Special Fund payments until the beneficiary’s “actuarial date of death,” or his assumed life expectancy, which is determined in advance. Only if the beneficiary outlived that age does the spouse have to repay what she collects.

For example: Former Cardinal Aluminum vice president Gene Daugherty died Jan. 13, 2015, in Louisville at age 85. But the Special Fund took no notice of his death and kept paying workers’ comp benefits into his bank account for five more years.

When the state tried to take back the $16,462 in over-payments, it learned that Daugherty’s widow, Doris, was in her 90s, suffering from dementia and had her own government benefits automatically deposited into the same bank account. Plus, as Daugherty’s wife, Doris might have been entitled to at least some survivors’ benefits. As of a May 2020 internal memo at the Special Fund, officials had not decided how to proceed against the widow.

“It is confusing,” Milligan acknowledged. “Sometimes the widow can continue collecting her husband’s benefits and sometimes she can’t, but the children never can, although they don’t always seem to understand that.”

‘Gone to bed at night crying’

Kimberly Rhodus was executrix of her father’s estate when he died in 2016, so she was responsible for paying his final bills, cashing his life insurance policies, disbursing his assets according to the terms of his will and making sure the proper government agencies knew of his death, such as the Social Security Administration.

While going through the Community Trust Bank checking account she shared with her father, Rhodus noticed among his income sources a biweekly payment of $555. Its source was simply listed as “KY Finance.” Unlike his other government benefits, these payments kept coming after he died.

“I asked at the bank. They didn’t know what this was,” Rhodus told the Herald-Leader this week. “They said, ‘If this was money you weren’t supposed to be getting, someone would have turned it off by now.’ So I figured this was some sort of survivors’ benefits that went to the family.”

In hindsight, Rhodus said, she wishes she had been more curious about “KY Finance.”

In March 2020, the Special Fund mailed her a letter to say it had just discovered her father was dead. It demanded “refund of all payments sent from March 26, 2016, through Feb. 29, 2020,” which came to $56,920. At that moment, her bank account was overdrawn to the sum of $289.

“I was like, ‘Oh my god, are you frickin’ kidding me?!’” Rhodus said. “Four years later — it took you guys four frickin’ years to figure this out?!”

Rhodus said she soon talked on the telephone with two different employees at the Special Fund, a man and a woman, both of whom left their jobs before they could finish processing the personal financial paperwork she submitted. The woman chided her for not contacting the Special Fund’s offices when her father died.

“She said, ‘You needed to come to us with proof of death, like a death certificate, as soon as he was deceased,’” Rhodus said. “And I’m like, ‘I don’t even know who you are or where you are or what you do. This is the first time I’m hearing about a Special Fund. How would I know I’m supposed to take a death certificate to you?’”

The Labor Cabinet sent Rhodus’ file to Franklin Commonwealth’s Attorney Larry Cleveland for prosecution for a Class C felony, theft of more than $10,000, which could send her to prison for five to 10 years. Cleveland filed the charge but put the criminal case on hold after Rhodus reluctantly agreed to a repayment plan.

The $500 that Rhodus must pay to the Special Fund on the first of every month is about as much money as her car payment, which happens to be four months past due, she said. Without a steady income, she’s borrowing from her boyfriend.

“I’ve gone to bed at night crying, worrying about where this money is going to come from and whether I’m going to prison,” she said.

“They don’t realize the stress they’re causing people,” she said. “How many people out there around Kentucky are getting these letters?”

KY workers’ comp agency gives big executive bonuses while ending salary transparency

While thousands waited for help, state workers gamed the system to collect jobless benefits

This KY man was wrongly jailed for 14 months. Then they billed him for his stay.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance