Having Limited the Sale of Dirty Trucks, the EPA Now Looks to Derestrict Th

From the June 2018 issue

It’s a common-enough scenario: owner wrecks vehicle, saves powertrain for transplant into something else. But in the trucking industry, such a simple concept has evolved into a controversy large enough that, in 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency moved to limit sales of trucks with transplant powertrains through a reinterpretation of the Clean Air Act. The rule took effect on the first of this year. Now the EPA’s current chief, Scott Pruitt, is already looking to undo it.

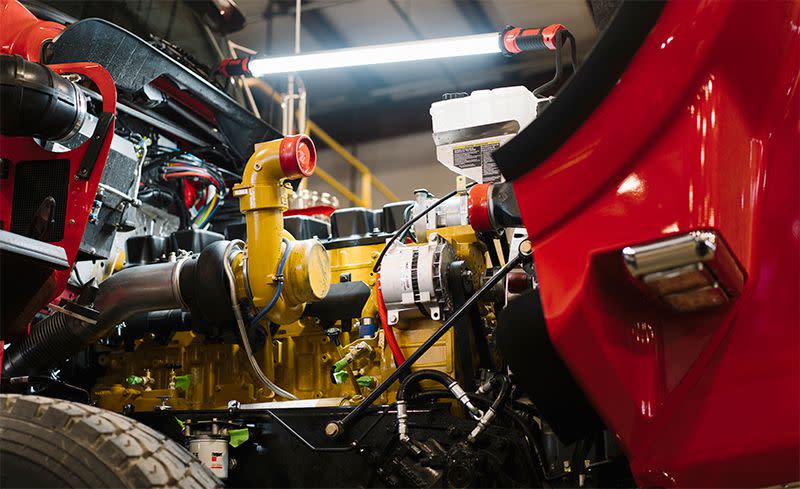

The big semi brands-including Kenworth, Freightliner, and Peterbilt-sell new trucks sans drivetrain; these trucks are called gliders. Even after the donor drivetrain is installed, a glider can cost up to 25 percent less than a new truck while usually offering better safety and comfort features than the older truck from which its engine, transmission, or axles derived. But because they aren’t considered new vehicles under federal law, gliders haven’t been held to current emissions standards.

Before 2010, glider production was a small business, with annual output below 1000 units. But then a number of companies began to take advantage of the less-stringent emissions standards, and by 2015, glider production had crested 10,000. The regulation Pruitt is seeking to overturn limits a manufacturer’s glider sales to just 300 per year.

According to the EPA, most recent gliders have engines built between 1998 and 2002. When the agency tested the trucks last year, it noted that particulate-matter pollution was 55 times greater and NOx emissions 43 times higher than that from trucks manufactured in the 2014 and 2015 model years. Prior to Pruitt’s call for repeal, the EPA had already laid out the intent of the glider-truck proviso: to prevent air pollution from diesel particulate matter-better known as soot. It’s no secret that diesel exhaust is harmful to human health. The California Air Resources Board identified diesel particulate matter as a toxic air contaminant way back in 1998. In 2012, the International Agency for Research on Cancer-part of the World Health Organization-added its own assessment: Diesel soot can cause cancer. CARB says that, in addition to causing smog and haze, elevated diesel particulate matter in the air can lead to heart disease, aggravate asthma, encourage other respiratory problems, and in some cases prove fatal. The EPA noted in 2016 that an additional three years of production for glider trucks built with high-pollution pre-2002 engines could lead to as many as 6400 premature deaths.

Pruitt’s EPA received nearly 135,000 comments on the proposed repeal, many of them critical of reopening a truck-sized loophole that had already been closed. Detractors included the American Lung Association, Navistar (manufacturer of International-brand trucks), the National Association of Manufacturers, Volvo, and UPS, with concerns running the gamut from poor air quality to unfair competition. Luke Tonachel, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s clean vehicles and fuels project, says reopening the glider-truck loophole “would be politics trumping public health.” But so far, Pruitt has steered his EPA toward looser regulations. Get ready to hold your breath.

Withdrawals

In calling to reopen the glider loophole, EPA head Scott Pruitt cited a recent study by Tennessee Technological University that found the 10-to-15-year-old refurbished engines to be no worse, emissions-wise, than new emissions-compliant diesels. That study was paid for by Tennessee-based Fitzgerald Glider Kits, the nation’s largest seller of glider trucks, which also announced last year that it would build the Tennessee Tech Center for Intelligent Mobility on land the company owns. Amid the rancor that followed, the university withdrew the study and initiated an internal ethics investigation. The interim dean of its College of Engineering, Darrell Hoy, has since called the findings “far-fetched” and “scientifically implausible.”

Automakers Oppose CA EV Mandate While Helping CARB States Meet It

Bosch Claims a Diesel-Emissions Breakthrough, But Is It Too Late?

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance