Fall by John Preston review – the truth about Robert Maxwell

Soon after he took over the New York Daily News – his last and most foolish purchase – Robert Maxwell asked the tabloid’s publisher, Jim Hoge, if he could do him a favour: “Would you mind,” Maxwell asked, “if I stood here with the door open and shouted at you for a while?” Hoge had known worse requests; the paper had recently emerged from a long and bitter struggle with the print unions, and its circulation was under the thumb of the Mafia.

“I told him to go ahead,” Hoge said, remembering the incident to John Preston. “Immediately, Maxwell started lacing into me, banging on my desk with his fist and saying how it was outrageous that I had an office that was larger than his. After about 40 seconds of this, he said ‘Thank you’ in a much quieter voice and went out.”

Hoge later discovered that Maxwell had staged this little scene to impress the youngest of his nine children, Ghislaine, who had noticed the difference in office sizes and was now within earshot. But to impress her how, exactly? As he was about to make Ghislaine his “emissary” in New York, it may have been intended as a lesson in how to treat underlings. More likely, it was just Maxwell being Maxwell – showing off to his daughter, keen to attract attention to himself whenever a suitable moment arose.

To Clive James at Cannes, Maxwell looked like 'a ton and a half of half-cured ham wrapped in a white tuxedo'

His size alone made him hard to ignore – 22 stone in the lean years – but Maxwell added props to make his figure even more memorable. Cigars, dinner jackets, and a visit every week by the Savoy’s head barber to dye his hair and eyebrows jet black; I remember that when he took command of a Glasgow newspaper in the 1970s (a brief episode that this book doesn’t mention) there was also talk of a corset. The voice – “Churchill’s rumbling cadences [with] an extra helping of treacle”, as Preston describes it – came out of his early encounters with the English language, listening to the prime minister’s speeches during the war. “This Was Their Finest Hour” featured in his Desert Island discs.

The effect varied according to the witness. To Clive James, spotting him at the Cannes film festival, he looked like “a ton and a half of half-cured ham wrapped in a white tuxedo”. To a print union negotiator in New York he seemed “like an English nobleman”. To Rupert Murdoch, whose esteem he craved, he was never more than a crook and a buffoon.

The two media magnates had names with the same initials, the same number of syllables – they might have been invented for a Jeffrey Archer novel, but for the fact that they disobeyed a cardinal rule of popular fiction: in novels about rivals, the poorer must outsmart the richer because his wits have been honed by his early struggle. Murdoch edited the school magazine, went to Oxford, and inherited his dad’s newspaper in sunny south Australia. Maxwell, born in Ruthenia, an obscure province in central Europe, had a father, Mehel Hoch, who traded in animal skins and toured the countryside with a mule to carry them between seller and buyer. The Hochs had nine children, two of whom died young, and lived in a two-room wooden shack with earthen floors and a cesspit at the back. Also, they were Jewish. After Maxwell, then known as Jan Hoch, left his native town in June 1939 he never again saw his parents, his grandfather, his younger brother or three of his five sisters. Auschwitz claimed six of them; the seventh, his sister Shenya, disappeared after her arrest in Budapest. Jan Hoch, meanwhile, went through several changes of name and eventually reached Britain via Beirut and Marseille.

Three weeks after D-day, he was back in France, first as a sergeant and then as junior infantry officer fighting his way east across Europe. For his “magnificent example and offensive spirit” in rescuing a trapped allied platoon, he was awarded the Military Cross. He read books constantly and excelled at languages (by 1945, English, German and French had been added to Yiddish, Hungarian, Czech and Romanian). A fondness for disguise and what Preston calls “a natural flair for subterfuge” made him useful to British intelligence in ruined Berlin, which is where he met the publisher Ferdinand Springer, whose distinguished backlist of scientific books and journals lay heaped in a large warehouse 100 miles from the city, safe from British and American bombing. Industry and academia in allied countries had been cut off from German research since 1939 and they were keen to catch up on it. Maxwell set up a company, reached a worldwide distribution deal with Springer-Verlag, and arranged to have the stock – 300 tons of books and journals – transported to London by freight train and a convoy of lorries. The company was funded by MI6. It was the foundation of all Maxwell’s later success.

By the time he was 25, he had proved himself quick-witted, bold, clever, resourceful and ruthless. Cruel, too: in the last weeks of the war, he executed a local mayor in the square of a German town (not named) by shooting him through the head, and, later, allegedly killed a group of young German troops who had already surrendered. He married Betty, a French Protestant, in Paris in 1945, and was quick to write down for her his six rules for a happy marriage, beginning: “1, Don’t nag, 2, Don’t criticise unduly … ” Half a century later she recalled in her memoir how his normally full lips could sometimes tighten to strips “thin as filaments of blood” depicting “death and carnage”.

Murdoch, however, was a different kind of opponent, one that had taken up residence inside Maxwell’s head. Preston contends that Maxwell’s obsessive interest in him – his need both to emulate and beat him – set in train a course of events “that would lead to his physical and mental disintegration, his downfall and, ultimately, his death”. Those events began in America in the late 80s, but the rivalry was 20 years older, dating to Fleet Street in the 60s.

Newspapers fascinated Maxwell, as they do many egoists, but somehow Murdoch managed to outwit him whenever he tried to get his hands on a newspaper business. It happened with the News of the World, the Sun, Today, the Times and the Sunday Times. Often it was Maxwell’s fault: he had an incontinent tendency to brag about a deal before the contract was signed. In the case of the News of the World, however, darker forces were at work. In 1968, the weekly anthology of smut that was then Britain’s biggest selling newspaper enjoyed the ownership of the eccentric Jackson family, one of whose members was the bisexual amateur jockey Professor Derek Jackson, a lover of Francis Bacon and recently married for the sixth time. To fund this complicated lifestyle, Jackson decided to sell his 25% stake in the family company. Maxwell made a generous offer, to be rebuffed via an editorial in the News of the World by the editor, Stafford Somerfield, who argued that “it would not be a good thing for Mr Maxwell, formerly Jan Ludwig Hoch, to gain control of … a newspaper which I know is as British as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding”. “This is a British newspaper, run by British people,’ he concluded. Let’s keep it that way.”

Even in 1968, the year of Enoch Powell’s “rivers of blood” speech, the editorial caused outrage – which had, from Maxwell’s point of view, the unfortunate effect of reviving Murdoch’s own hopes of buying the paper. He flew to London and found the Jackson family receptive: Murdoch might speak with a ghastly accent but at least he wasn’t called Hoch. Xenophobia – possibly with a twist of antisemitism – had opened the door to Murdoch’s global advance. As Harold Evans, who knew both men, observed: “Maxwell thought he’d entered the ring with another boxer … In fact, he’d entered the ring with a ju-jitsu artist who also happened to be carrying a stiletto.”

But he continued the hopeless struggle. Not content with acquiring Mirror Group Newspapers and rigging the spot the ball contest, he looked west to the US, where Murdoch was emerging as a big player. Maxwell was a man without friends – sycophants were a different matter – but in the property developer Gerald Ronson he had someone who came close to an idea of one. It was Ronson who encouraged him to buy the yacht that the brother of Adnan Khashoggi, the Saudi arms dealer, wanted rid of when it was still half-built on the stocks. It was Ronson, too, who encouraged him to return to Judaism – “How come all of a sudden you’re not Jewish any more?” he asked him in 1984, by which time Maxwell had denied – or at least never willingly admitted - his Jewishness for 40 years.

When Ronson heard of his American ambitions, he was discouraging. But Maxwell wasn’t to be put off. In Ronson’s words: “Maxwell had to be in America, and he had to be bigger than Murdoch.” In 1988 he overpaid for Macmillan US ($2.6bn) and the Official Aviation Guide ($750m) in a spending spree that culminated in the tottering New York Daily News, for which any price at all was too much. To raise the cash, he borrowed from a total of 44 banks and financial syndicates, all of them anxious to lend as much as he wanted. The conclusion of the Department of Trade and Industry’s 1971 report into Maxwell’s affairs – that he wasn’t fit “to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company” – had been long forgotten.

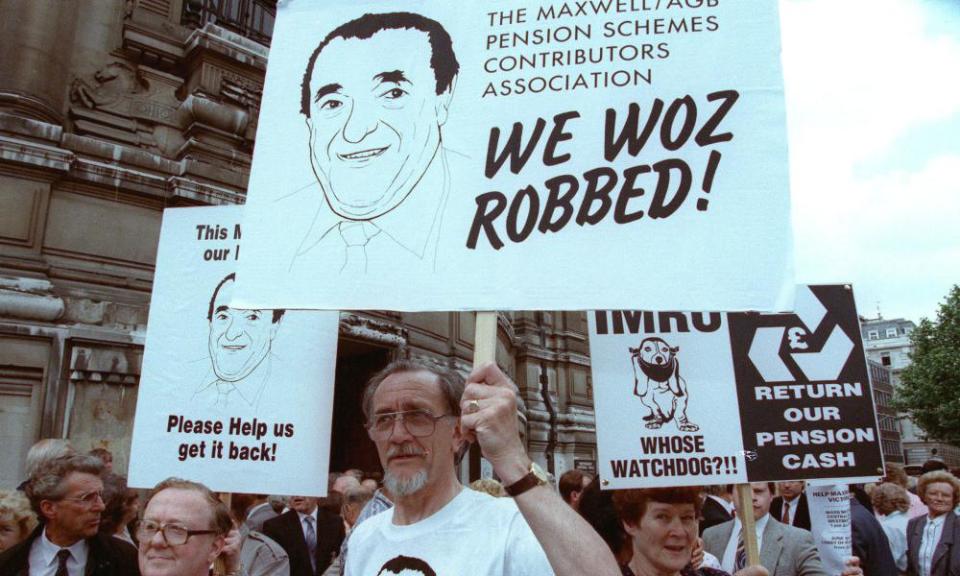

We know the rest. Profits fell, interest rates soared, a full-blown recession loomed. The banks wanted their money back and Maxwell’s share price needed support. Assets were sold – even Pergamon publishing, which had been the core of the business from the beginning. Eventually, his only solution was to rob the Mirror pension fund; and, when he knew that was close to discovery, to jump from the stern of his boat.

Preston’s biography is largely anecdotal, without too much concern for context. The stories are good and Preston tells them with his gift for the kind of wry comedy that suits English decline. The “mystery” in his book’s subtitle surely refers to his behaviour in life rather than the manner of his death – of his family only Ghislaine believes he was murdered (oddly, given that her last instruction to the yacht’s crew was to “shred everything”). The picture of Maxwell that emerges is vivid but familiar: bombastic, florid, devious, gluttonous, bullying, absurd. But why was he these things?

Ghislaine was his favourite child, but that hadn’t always been so. According to Preston, her parents had rather ignored her until, aged three, she stood before her mother and said simply: “Mummy, I exist.” Her father may have been trying to make a similar point, but to himself as much as to his audience.

• Fall: The Mystery of Robert Maxwell is published by Viking (RRP £18). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance