Here's the real money-maker for the Internet of Things

Why hasn’t the Internet of Things become a thing?

Trust me—the name isn’t helping. What does “the Internet of Things” even mean? Our household objects do not have their own internet. There’s no little Twitter for thermostats, or Facebook for waffle irons.

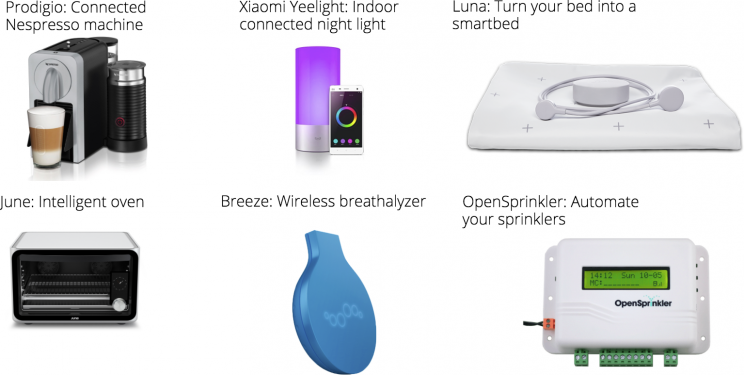

Oh, there’s an infinitude of networkable “smart” products available—lights, thermostats, coffee makers, security cameras, door locks, sprinklers, robot vacuums, smoke detectors, microwaves, pool cleaners, baby monitors, bike locks, shower heads, crockpots, coffee mugs, soccer balls and basketballs, bathroom scales, bikes, and rolling luggage. All of it networked, all of it connected to apps on your phone.

There is not, however, a corresponding rush of people buying this smart stuff.

Consumer IoT

Sure, some early-adopter techies have installed smart thermostats and light bulbs. The Nest thermostat, for example, programs itself by observing what time you come and go, and the Honeywell Lyric uses your phone’s GPS to know when you’re approaching the house, and get it heated or cooled in advance. You can also adjust your home’s temperature and lighting from a phone app.

But mass adoption of IoT? Nope, not yet. I can count the number of people I know who own, say, an internet-connected mattress on zero fingers.

The industry’s rush to Thing-ize every ever-loving household object, no matter how silly, isn’t helping much with the category’s reputation. The following are actual products:

IoT water bottle. There are actually five of these. They track how much water you drink.

The IoT doggie-treat dispenser.

The IoT toilet-paper holder. Lets your phone know when the roll needs replacing.

The IoT umbrella.

The IoT fork.

The IoT toothbrush.

The IoT trash can.

The IoT tampon.

The IoT egg tray. Yes, from anywhere in the world, you can now see how many eggs you have left.

Upon discovering that a remote control came with our new TV in 1979, my mom said, as I recall: “Why does anyone need this? Is it so hard to walk six feet to change the channel?”

That seems to be the public’s response to IoT devices: “Why do I need this thing?”

And also: “Am I really going to open an app to turn my lights on?”

And also: “What about security? The more entry points I offer to hackers on the internet, the easier I am to hack!”

You may recall that last month’s massive internet outage—of Twitter (TWTR), Reddit, Netflix (NFLX), Airbnb, and Spotify—was made possible by a weakness in IoT webcams made by a Chinese company called Hangzhou Xiongmai Technology.

Industrial IoT

But here’s the thing: Most people (and most reporters) who use the term “Internet of Things” are talking about consumer products. And sure enough: IoT adoption in consumer products isn’t what you’d call white hot.

There is, however, a second IoT universe where these technologies make a lot more sense: Industrial and commercial uses.

A typical corporate building is made up of systems: security systems, fire/smoke/water-alarm systems, heating/cooling systems, lighting systems. If they can be made to communicate intelligently, both with each other and with building managers, they can provide a huge boost in convenience, savings, safety, and environmental payoff.

At this very moment, gas companies are installing sensors on remote pumping stations in Alaska, so that their engineers can monitor the machinery’s health with an app instead of driving out there for inspection. Tire companies are embedding sensors into their tires, and sharing the collected data to trucking companies to save fuel and money. Sensors in municipal water utilities can predict when machines will fail, so they can be fixed before disaster strikes. Predictive maintenance, it’s called.

Some people call this realm IIoT, the Industrial Internet of Things. In business, it’s not about not getting up off the couch to flip a light switch. It’s about efficiency, data, interconnectedness of systems—and big, big money. According to Accenture, corporations will be spending $500 billion a year on these technologies by 2020.

Usually, new technologies seep into the corporate world through the back door, when employees bring their personal technologies and devices into the workplace (see: smartphones, social media). But in the case of the Internet of Things, it looks like industry will lead the way.

You may not be completely sure why anyone needs to build sensors into, write an app for, and generate data from a waffle iron.

But in the commercial world, when the “things” in question are big, expensive, dangerous, and mission-critical pieces of equipment, the “why” of sensors, data, and apps is screamingly clear.

David Pogue, tech columnist for Yahoo Finance, welcomes non-toxic comments in the Comments below. On the Web, he’s davidpogue.com. On Twitter, he’s @pogue. On email, he’s poguester@yahoo.com. Here’s how to get his columns by email.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance