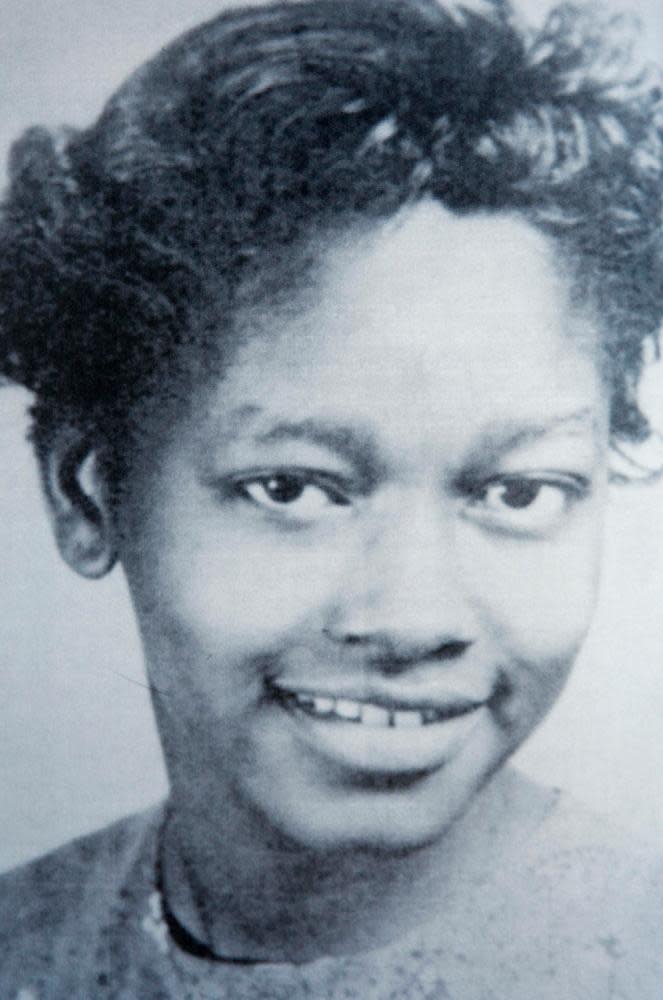

Claudette Colvin: the woman who refused to give up her bus seat – nine months before Rosa Parks

It was 2 March 1955, and an unusually humid spring day when students at Booker T Washington high school, a segregated school in the heart of the Jim Crow south, had been let off early to make their way home. A group boarded a segregated public bus, which wound through segregated neighbourhoods gradually filling up with passengers.

A 15-year-old gifted Black student, with aspirations to become a civil rights attorney, took a window seat near the exit door. She gazed outdoors until the white driver instructed her to give up her seat for a white passenger standing nearby.

Claudette Colvin refused.

It may have been 65 years ago, but Colvin still remembers it all in vivid detail, almost drawing the scene with her flowing hand motions and words. “History had me glued to the seat,” she says, tapping her shoulders. “It felt as if Harriet Tubman’s hand was pushing me down on the one shoulder, and Sojourner Truth’s hand was pushing me down on the other. Learning about those two women gave me the courage to remain seated that day.”

As two white police officers dragged her from the bus, her body went limp. She shouted repeatedly: “It’s my constitutional right.” She was handcuffed, placed in jail and charged with violating segregation laws, disturbing the peace and assaulting a police officer. She pleaded not guilty, but was convicted. (Two of the charges were dropped on appeal.)

Colvin’s unplanned act of bravery was almost written out of civil-rights history. The Montgomery bus boycott began nine months after her arrest, spurred by the arrest of Rosa Parks in an almost identical incident, so the story went. That was until revisionist historians, a handful of journalists (notably Gary Younge) and Phillip Hoose’s National Book award-winning biography of Colvin corrected the record in the early 00s. In truth, the actions that Colvin took on that warm day in March planted the seed for the boycott and, critically, the legal foundations to challenge transportation segregation laws in federal court. She was an unsung hero of the movement, clumsily labelled “the original Rosa Parks”.

* * *

We meet on a bright February afternoon at a retirement home in Birmingham, Alabama – the city of her birth. Seated outside, masked and socially distanced, Colvin is immaculately dressed in a grey blazer and red jumper, her hair neat in short, tight curls. She is candid and mild-mannered – telling the long, formative stories of her childhood in great detail.

She grew up in the rural town of Pine Level, Alabama, about 30 miles from Montgomery, on a farm run by her great-aunt and uncle. But even as a small child, surrounded by farm animals, two pet dogs and idyllic countryside, she felt the burden of racial oppression. “You didn’t understand it, but you saw the differences,” she recalls. “I only interacted with white people when I left the farm and went to the general store to pick up supplies. That’s where I learned about racism.”

She was about six, waiting in line, when a group of white children began pointing and laughing. “One little white boy approached me and said: ‘Let me see your hands.’ So I raised my hands up, and then he approached me, and he touched my hands.” Almost immediately, her mother gave her a backhand slap across the mouth – her hands re-enact the swing, and she can still recall how much it hurt. “I was crying, but that’s when I realised we weren’t supposed to touch each other.”

Aged eight, she moved to Montgomery, to the low-income Black neighbourhood of King Hill. It was here, as she entered adolescence, that her experiences paved the way for 1955. Her sister Delphine died from polio just days before she started high school. She recalls in Hoose’s biography, Twice Toward Justice, how the experience awakened her: “One thing especially bothered me – we Black students constantly put ourselves down … And the N-word – we were saying it to each other, to ourselves. I’d hear that word and I would start crying. I wouldn’t let people use it around me.”

The brutality of white supremacy manifested itself most violently later that year. Her neighbour Jeremiah Reeves, a pupil at Booker T Washington, who was just 16, was sentenced to death by an all-white jury for the rape of a white woman. Reeves had retracted a confession, made under duress, prompting the intervention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Colvin still thinks about her old classmate to this day. He was executed in the electric chair shortly after turning 22. She recalls his good looks, his clean white shirts and tennis shoes, and his special talent as a jazz drummer. She would often watch him play at the community centre in King Hill. “Everyone saw the injustice, the double standards,” she recalls. “At the time Jeremiah was on death row, Black men were saying: ‘Do not look at a white woman you see walking down the street … cross the street and pretend you have to tie your shoelaces. Do not make eye contact with white women.’”

Reeves’ case was the first time Colvin had seen the NAACP in action. At school, she was encouraged to critically engage with the plight of Black citizens. She learned about the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya; she was taught literature, from Edgar Allan Poe (her favourite author) to Black poets such as Paul Laurence Dunbar. In the days just before she refused to give up her seat, her teacher asked the students to write an essay, during what was then Negro History Week. It was titled: How Do You Feel As an American?

She was instantly struck by the title of the assignment. “We wasn’t considered Americans,” she says, anger still pulsating through her words. “We was considered negroes. And we was treated by the ruling class as second class citizens.” She wrote about the injustice of the Jeremiah Reeves case.

* * *

Today, Colvin still remembers the sound of the cell door slamming shut on her after her stand on the bus. The fear she felt alone inside jail. The prayers she recited before she was released.

The events of 2 March 1955 are still a source of major pride, but also of significant trauma. She doesn’t dream directly of her experiences that day any more, but after all these years still has recurring anxiety dreams – of being locked outdoors, trying to find an address or an entry code to a building that she has forgotten. “I think it’s connected to the doors closing, but also just not being able to get into places [during segregation].”

Although she is now accustomed to journalists asking her to recall the details, she rarely talks about it with her friends from the time. But she speaks regularly to her cousin Aileen, who visited Reeves on death row. “We don’t talk about all the hardship,” she says. “We try to talk about the teenage stuff – her first boyfriend; who became the campus queen; who had money. We ain’t thinking about all those white people.”

But the last time Aileen called it was to discuss the 6 January insurrection. “She was so hurt,” Colvin recalls. “She said: ‘I knew white people was angry, they was angry back in the 60s. But I never knew they were so unruly.’” Did the mob of Donald Trump supporters remind her of the white supremacy she experienced during the civil rights era?

“To me, it shows a sign of fear in white people. Anger and fear,” she says, arguing that the proliferation of accessible technology and information has fundamentally changed the dynamics of power in the US and across the world. “White people have been getting away by the colour of their skin, and they’re not going to be able to get away with that any more. That’s why he said: ‘Make America Great Again’; that day is over. That day is gone with the wind. That day is never coming back. Because people even in the poorest part of Africa … they are enlightened now.”

Although Colvin’s arrest made a stir in the local media back in 1955, the local civil-rights campaign, led by a then little-known Montgomery pastor by the name of Martin Luther King Jr, ostracised her. This she attributes to a combination of factors: her age, her gender, her darker skin tone and the fact that a few months later she would become pregnant out of wedlock.

But in the immediate aftermath of her arrest, Colvin was approached by Parks, a secretary of the Montgomery NAACP and a seamstress. For a brief time, the two became close. Colvin would occasionally stay at Parks’ home and would serve as a mannequin for wedding dresses Parks had sewn.

“Rosa was just like her name, soft-spoken, soft-talking,” she breaks into an impression, elongating each word: “‘Claudette … I knew your mother, Mary Jane. And when I first got the news you were arrested, it hurt me so bad. They put you in a jail instead of a juvenile centre.’”

At the time Colvin was unfazed when Parks became the face of the bus boycott nine months later. She was pleased that adults in her community had followed in her footsteps and taken a direct stand. But retrospection leads to a different feeling now.

“They [local civil-rights leaders] wanted someone, I believe, who would be impressive to white people, and be a drawing. You know what I mean? Like the main star. And they didn’t think that a dark-skinned teenager, low income without a degree, could contribute,” she says. “It’s like reading an old English novel when you’re the peasant, and you’re not recognised.”

Two months into the boycott, her attorney, Fred Gray, approached her about a civil lawsuit that would become the Browder v Gayle case. The ruling, which was taken all the way to the supreme court, found that bus segregation was unconstitutional under the 14th amendment. Colvin was one of four plaintiffs and testified in court, a few months after giving birth to her son, Raymond.

Like other episodes in that period she recalls it all with clarity. The smell of the coffee, the prayer she said with her family before leaving for court. She faced hostile cross-examination by the city’s white attorney, Walter Knabe, but emerged as the star witness among four lead plaintiffs.

The city’s legal strategy had essentially been to frame the bus boycott as an orchestrated act of subversion directed by outside influences, namely Martin Luther King, and to argue that Montgomery’s Black residents had been largely satisfied by public transportation laws before his intervention.

Colvin was just 16 when she took the stand, recalling in her biography how she batted away Knabe’s questioning.

“Why did you stop riding the buses on 5 December?” he asked her.

“Because we were treated wrong, dirty and nasty,” she replied.

She recalls it now with a smile. “It was a little like I was on stage, and I had to give my best performance, like I was doing a Shakespearean play,” she recalls. But when the verdict came down, in June 1956, none of the civil-rights attorneys she had worked with told her. Instead, she found out on the news.

Colvin continued to struggle for opportunities in Montgomery, still ostracised by local leaders in the Black community while enduring the racism of the south. She abandoned her dreams of becoming a civil-rights attorney and in her early 20s moved to New York, becoming a nursing assistant.

For decades, her story went untold. She wouldn’t discuss it with the community she worked in, fearing they simply wouldn’t understand. It was not until she retired that she began opening up in public.

Today, she remains sanguine about the sacrifices she made as a teenager. “It’s like my mother said. Everything is designed. Your destiny is already mapped out, planned by God.” She points to the successes of her five grandchildren spread throughout the country. “I’m living the fruits of my labour through them,” she says.

Finally, Colvin has rightly claimed her place as a pivotal player in the struggle for racial equality during the civil rights era. There are streets named after her in New York and Montgomery. Before the pandemic, she toured schools to tell her story.

“Claudette Colvin’s story is a timeless profile in courage,” says Montgomery’s mayor, Steven Reed, who was elected in 2019, becoming the city’s first Black mayor. “It resonates just as much today as ever before now. Through Claudette Colvin, we have the rare chance to celebrate uncommon tenacity and bravery in someone who was so young.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance