The chips are down: Belgium counts the cost of betting all on the potato

A humble frite with a dollop of mayonnaise is a revered thing in Belgium but, thanks to campaigners against a new mega-processing plant, the environmental and social costs of its mass production are being newly questioned at the highest levels of government.

For three years, residents in Frameries, a town in French-speaking Hainaut in the south-west of the country, have battled against the proposed construction of a €300m (£258m) factory, which it is said would increase Belgian production of processed potato products by a third. Belgium is already the world’s largest exporter of pre-fried potato products.

The residents’ campaign group, Nature sans Friture or Nature Without Frying, has accused the company behind the proposed factory – Clarebout, the largest producer of frozen potato products in Europe – of being noise and air polluters, and poor employers. The claims are denied.

But what has been a long-running local spat is now making national headlines as developments over the last year have raised questions about the sustainability of a Belgian agribusiness model that has proven to be so brittle over the last year.

“Should we continue to be proud of being the biggest agro exporters of processed potatoes, and that American citizens eat our potatoes in their fast-food restaurants?” asked Céline Tellier, minister for the environment in the government of Wallonia, the Francophone southern region of the country. “I don’t think so – a global model I do not support.”

Belgium swept past the Netherlands in 2011 to become the world’s biggest exporter of frozen fries. According to the Belgian NGO Fian International, about 11% of Belgian arable land, excluding permanent meadows, is now used for potato cultivation.

The country produces 16 times the amount of potatoes necessary to meet its domestic needs, using vast amounts of pesticide and nitrogen-rich fertiliser in the process. Belgium ranks fourth in Europe among the largest users of pesticides per hectare behind Malta, Cyprus and the Netherlands.

But, for all that, the Covid-19 pandemic has been a disaster for Belgian farmers supplying the companies that dominate the processing and export market.

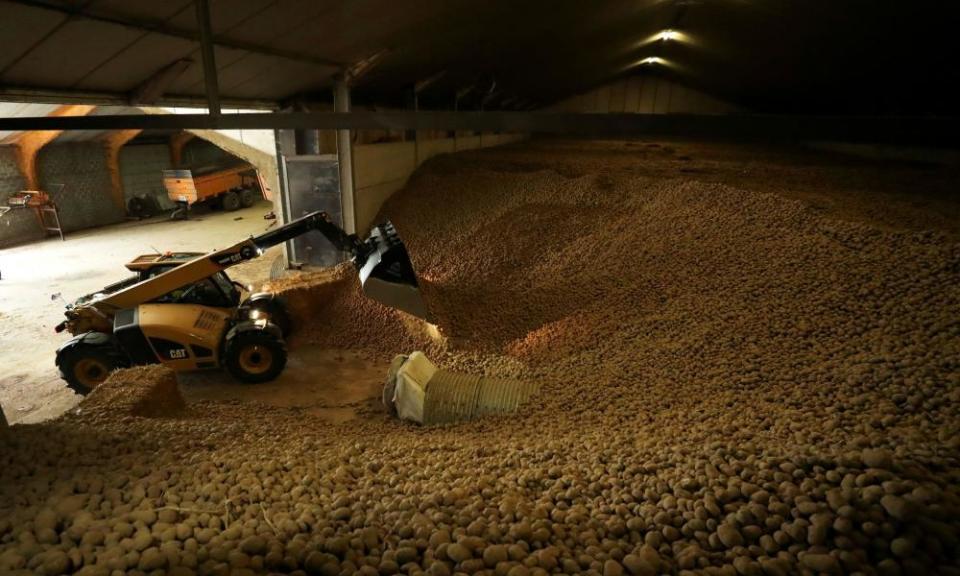

The farmers found they had no other buyer when the international market collapsed due to the closure of hospitality around the world. Hundreds of thousands of tonnes of potatoes were left to pile up in warehouses. The state was forced by the farmers’ plight to buy them up to give away to food banks.

“Let’s all eat chips twice a week, instead of just once,” implored Romain Cools of the potato growers’ union, Belgapom, at the height of the crisis. Others, however, are now looking at the bigger picture – and taking the view that the fightback in Frameries should be the start of something bigger.

Saskia Bricmont, a Belgian MEP in the Green group, said the proposed expansion by Clarebout, which boasted an annual turnover of €1.3bn (£1.1bn) in 2019, owing to its plants in Nieuwkerke and Warneton, had highlighted the need for a rethink of public policy.

“We have seen a transformation of the landscape with huge potato fields. People are working just for one enterprise, they are dependent and absolutely not resilient,” she said.

“Now it is the pandemic that has hit them but it could be climate change or other issues in the future. The farmers should be diversifying and have a diversification of markets. More and more farmers are seeing this. The Covid crisis has shown that it is necessary to be resilient and not dependent on global market and supply chains.”

Until the 1980s, the Belgian potato sector had been mainly based on local trade, cultivated by thousands of small and medium-sized farms that sold their produce for direct sale or to traders who supplied the small processing companies. But the following three decades witnessed a profound transformation.

Reforms of the EU’s common agricultural policy saw the growth of direct aid mainly calculated on the basis of agricultural area, spurring large-scale intensive farming. Meanwhile, global competition in the export market encouraged companies to specialise and concentrate in order to seek to achieve economies of scale and efficiency gains.

A multitude of traders and small processing companies gave way to the big six in Belgium – Clarebout, Lutosa, Agristo, Mydibel, Ecofrost and Farm Frites – who now control more than 90% of the processing market in the country.

Trading on the reputation of Belgian frites, or frieten as they say in Dutch-speaking Flanders, and encouraged to grow through the provision of public funds and state investment in roads and ports, the industry proudly announced three years ago that it had passed a symbolic milestone of five million tonnes of processed potatoes in a year.

“In 1990, some 500,000 tonnes of potatoes were processed into French fries, mash products, crisps or even flakes or aggregates,” said Belgapom, the industry’s lobby group. “Twenty-eight years later, the sector can boast a 1,000% increase.”

Clarebout has said it believes there are further “opportunities for growth worldwide” through investment in Frameries, which offers “the presence of cultivators who would like to grow potatoes, or who would like to convert to this type of cultivation”.

It insists it maintains the highest environmental and labour standards. “The motto of Clarebout is that nature is the root of our future,” a spokesman for the company said.

“We must take care of nature, of the people who cultivate the lands, those who work to produce good products from those natural resources, and of course take care of people who live close to our plants.”

But, giving evidence last week in front of a committee of the parliament of Wallonia, Florence Defourny, the lead spokesman of Nature sans Friture, made the case that what she has described as a “junk food factory” has no place just 15 metres from people’s homes.

Speaking to the Observer, Defourny had a further message of possibly wider resonance. “Belgian fries are best when they are ‘homemade’ and not industrial,” she said.

“Belgium should be thinking about the model that it wishes to support. The economy, OK, but not at any price.”

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance