Is Newmont's blockbuster gold deal ushering in a return to growth for growth's sake?

Newmont Mining Corp.’s US$17-billion bid for Australia’s Newcrest Mining Ltd. would be the largest merger in the history of the gold mining sector, so Newmont chief executive Tom Palmer’s splash over the weekend naturally has prompted lots of questions.

But one simple query kept coming up as analysts studied the proposal: Why?

Specifically, is Newmont, already the world’s largest gold miner, seeking to get bigger merely for the sake of increasing scale?

Absorbing Newcrest, the fourth largest gold miner, will be a challenge. Some analysts struggled to identify obvious synergies or strong regional overlaps that would help rationalize creating a US$57 billion gold mining giant. Those analysts wondered if Palmer was attempting to create a company that would be too large for its own good.

“Newcrest’s eight mines would add material complexity to Newmont and we would have concerns that this takes the company beyond the optimal manageable size,” Alexander Hacking, an analyst at Citigroup Inc., wrote in a note. “Operating synergies appear de-minimus.”

Fahad Tariq, an analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG, shared similar observations with this clients, and described Newmont’s bid as opportunistic given that Newcrest’s chief executive Sandeep Biswas departed in December and the company’s share price has underperformed.

Growing bigger for the sake of growing bigger is not a strategy

Barrick chief executive Mark Bristow

Both analysts questioned whether another miner, such as Barrick Gold Corp. or Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd., might join the chase for Newcrest and open a bidding war. Alas, neither company seems interested at the moment, adding to the perplexity of what Palmer is trying to achieve.

“We’re more focused on regions, and deals where we can surgically extract specific assets that make sense,” said Sean Boyd, executive chair of Agnico. “That’s our preference rather than just to sort of smash companies together without any sort of regional consolidation benefits or synergies.”

Likewise, Barrick chief executive Mark Bristow told the Financial Times that his company wasn’t interested either. “Growing bigger for the sake of growing bigger is not a strategy,” he said.

Growth for growth’s sake

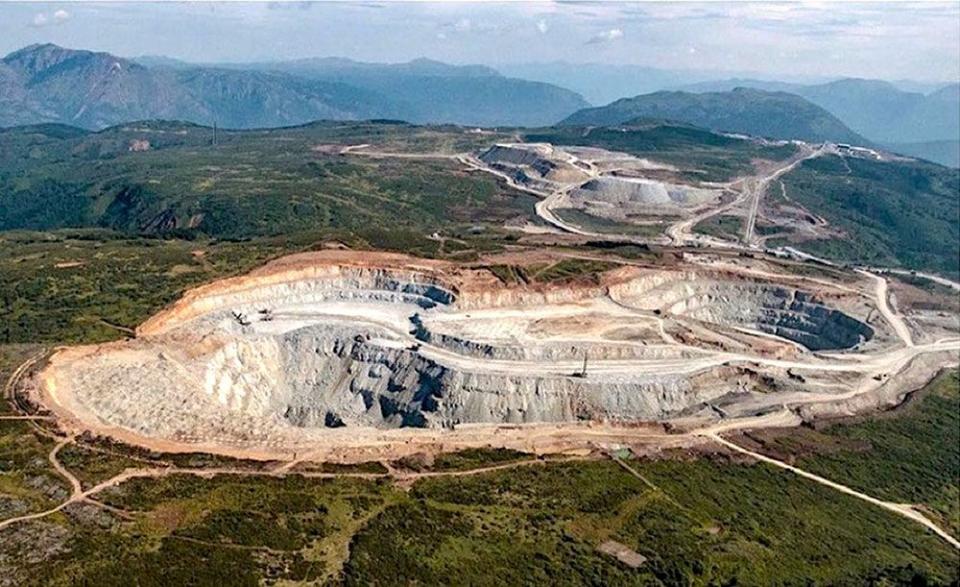

Denver-based Newmont and Melbourne-based Newcrest each have significant footprints in Canada. They have mines in British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec and each company is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. The merger could also have an impact on Canada’s large gold mining sector, which has struggled to attract investment in recent years for reasons executives often debate.

The idea of “growth for growth’s sake” is freighted with meaning in the gold mining sector, as many executives often blame their industry’s troubles on just such a strategy. In an oft-cited presentation from the Denver Gold Forum in 2017, Marcelo Kim, a partner at major bullion investor Paulson & Co., criticized the gold mining sector over a penchant for consolidating for no good reason.

Kim said the strategy had pushed many companies to overpay for asset acquisitions that subsequently left them debt-ridden. By his calculations, gold mining companies had recorded $85 billion in impairment charges between 2010 and 2017 — too high relative to the overall size of the companies in the sector, he said.

In recent years, many gold mining executives have forsaken “growth for growth’s sake,” and some of the largest mergers occurred at zero- to no-premium, such as Barrick’s 2018 US$6 billion acquisition of Randgold Resources Ltd. In announcing that deal, Bristow took pains to differentiate it from the mega-mergers that had preceded it.

“The merger will deliver value based on not a takeover premium, in fact … no takeover premium,” Bristow said in a call with analysts on Sept. 24, 2018. Rather, he said no premium was necessary because the value of the assets would naturally grow when the assets were combined under one management team.

New phase

It marked a change from deals in which acquiring companies paid a premium to the target company’s shareholders.

“We were in that empire building phase … where companies were just trying to buy whatever they could buy just to get bigger,” said Boyd. “Then sort of there had to be a deconstruction of that.”

Boyd reckons “deconstruction” — in which companies paid down high debt levels — started around 2015. By that point, gold prices had fallen from a peak in 2011 above US$1,900 per ounce and settled into a range of between US$1,100 per ounce and US$1,400 per ounce where they remained until late 2019, according to data from the World Gold Council.

But if the “deconstruction” was successful, it’s not clear that investors have yet forgiven gold mining companies for past mistakes.

For example, since mid-February 2020, just before the pandemic reached North America, gold prices have risen from US$1,310 to US$1,875 — about 30 per cent. Meanwhile, the VanEck Gold Miners ETF, which is indexed to the largest gold mining equities, is essentially flat at US$30.16 per share, given it traded at US$30.65 per share on Feb. 17, 2020.

Boyd said many gold miners are interested in achieving more scale because the largest global investment funds prefer to take positions in companies that have enough liquidity for them to easily unload their shares.

At the moment, even the largest gold mining companies — Newmont, Barrick and Agnico with respective market capitalizations of US$37 billion, US$32.6 billion and US$23.8 billion — are a fraction of the size of the largest companies in other sectors such as tech and energy, or even other commodities such as iron ore and steel.

“That’s part of it, investor size,” said Boyd. “A big part of the consolidation going forward will be there’s still too many companies, and there’s not enough really good opportunities.”

‘Challenging business’

He predicted there would be more consolidation in the industry, in part to satisfy investor’s desire for larger, more liquid gold mining companies, but also to achieve better more profitable companies.

Agnico in November struck a deal to acquire a 100 per cent interest in Canadian Malarctic, a gold mine in Quebec, that it had co-owned with Yamana Gold Inc. Putting the mine under one management team offered obvious synergies by eliminating overlapping management.

But Boyd noted that Agnico also operates mines throughout that region, known as the Abitibi, straddling Quebec and Ontario. That ties into Agnico’s growth strategy of finding the best mines within concentrated regions, so it can build ties to local communities and government. That’s what builds long-term value, Boyd said.

Of course, Newmont’s Palmer said in a press release that acquiring Newmont was more than simply scale because it “would join industry-leading portfolios of assets and projects to create long-term value across the combined global business.”

Neither Palmer nor a Newmont representative were available to comment on Feb. 6.

Under the terms of the deal as proposed, Newmont would pay a 21 per cent premium to Newcrest’s closing price on Feb. 3, and own 70 per cent of the combined entity while Newcrest shareholders would own the remaining 30 per cent.

Newmont’s shares dropped about five per cent on the day after the Newcrest bid was announced, while Newcrest’s Toronto-listed shares surged about 14 per cent to their highest since May.

Whether or not the deal moves forward, Boyd predicted there still needs to be consolidation in the gold mining sector. But to avoid the pitfalls of the past, he said the deals need to have a logic.

“It’s a challenging business,” Boyd said. “There’s a lot of risk and I think what companies are seeing now is, in some ways, it can be cheaper to buy production — if that production fits with your current strategy.”

• Email: gfriedman@postmedia.com | Twitter: GabeFriedz

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance