A Beginner's Guide to Value Investing

Investing in stocks is one of the most powerful ways to attain financial independence. It's also a great way to lose money if you don't have a sound, disciplined strategy and a long-term mindset. Furthermore, if you're still a beginner, trying to figure out which of the thousands of stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and ETFs you can buy are the best choices can feel overwhelming. After all, this is your hard-earned money you're putting at risk.

And that can all make value investing, a strategy that's designed to both reduce risk and unlock potential profits, appealing for many new investors. Furthermore, even if you're not a value investor at heart, there are aspects of value investing that can prove helpful for investors of all stripes. Let's take a closer look at what value investing really is, as well as how it can be applied to your own investing strategy.

Image source: Getty Images.

What is value investing?

Value investing seeks stocks selling at a discount to the value of their assets or to their cash flows. When a company sells for a discount to the intrinsic value of the assets it owns or the cash flows those assets produce, investors immediately gain some margin of safety, since they now own an asset that's worth more than they paid. Furthermore, you should be able to eventually make a profit when the market realizes the mismatch between what a stock trades for and what it's actually worth. In a worst-case scenario, even if the business were to fail and its assets were sold off (liquidated), the value of those assets would protect investors from losses.

What makes value investing attractive is the combination of its "defensive" nature and the potential for profits when buying an asset for less than its intrinsic value. Though it can require patience and time, holding a value stock while waiting for the market to reprice the asset to a more appropriate -- and hopefully higher -- value can deliver meaningful gains.

Value investing has evolved over time. Its roots are in the Great Depression and its aftermath, when the focus was purely on buying companies whose assets were worth more than the stock traded for. It has grown into more fundamental analysis of a company's cash flows and earnings, its competitive advantages, and finding stocks that are deeply discounted based on those things -- not only the liquidation value of their assets.

So how do you find a value stock? With fundamental analysis, which is the process of studying a company's financial reports to determine how much it is worth based on its assets and cash flows.

Successful value investors

Benjamin Graham

Graham is generally regarded as the father of value investing. Graham's Security Analysis, published in 1934, and The Intelligent Investor, published in 1949, established the precepts of value investing, including the concept of intrinsic value and establishing a margin of safety in the price you pay versus the value of the assets you buy. Graham's strategy was often referred to as "cigar butt" investing, on the (rather disgusting) idea of picking up discarded cigar butts that still had a puff or two remaining in them.

Besides the two invaluable tomes above that Graham authored, his most lasting contribution to value investing is likely to prove to be Warren Buffett, who studied under Graham at Columbia University and worked for a short time at Graham's firm.

Warren Buffett

The CEO of Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK-A) (NYSE: BRK-B), Buffett is perhaps the best-known value investor. Buffett cut his teeth in value investing in his early 20s and would use the strategy to deliver immense returns for investors in his partnership in the 1960s and then for Berkshire investors when he first took control of the company in the 1970s. However, the influence of Charlie Munger, Berkshire's vice chairman and Buffett's investing partner for many decades, along with Buffett's evolution as an investor, has changed Buffett's strategy from purely buying undervalued assets to identifying high-quality businesses at reasonable values.

This famous Buffett quote best describes why his thinking on value has changed over the years: "Better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than a fair business at a wonderful price." Buffett has used his acquisition of Berkshire Hathaway, which was a struggling textile producer, as an excellent example of this thinking. He has said that buying Berkshire has likely cost investors many billions of dollars in lost returns; after all, he ended up selling off essentially many of the company's textile-producing assets at a loss.

Perhaps the best evidence of this is that nobody associates Berkshire Hathaway with textiles these days. When Berkshire is mentioned, it's Buffett and Berkshire subsidiaries like GEICO insurance and stocks in Berkshire's portfolio, including Coca-Cola (NYSE: KO) and American Express (NYSE: AXP), that come to mind.

Shelby Cullom Davis

Davis took a different approach to value investing, beginning in the late 1940s with a focus on the insurance industry. One of the key aspects of the insurance industry that made it attractive to Davis is how insurers generally make money. Despite common misconception, few insurance companies make money on the policies they write. In general, an insurance company's goal is to break even on policy underwriting and to generate a profit from the investments it makes with the "float," which is the money from premiums it collects and holds until it must pay claims.

If one were to distill Davis' approach down to a few key things, it is these: Find insurance companies trading for a low P/E, or price-to-earnings ratio, and with well-regarded management teams; analyze the assets the insurer invests in, avoiding those that invest in high-risk assets such as junk bonds (debt issued by companies with weak credit ratings); drill down even further to identify insurers with special competitive advantages, including regulations that limit competition or a track record of successful underwriting in a specific kind of insurance.

Davis' investing career lasted from 1947 to 1994, growing the $50,000 he started with to nearly $1 billion at the time of his death. His legacy continues to this day, with both his son and grandson having become incredibly successful investors in their own right.

Joel Greenblatt

One of the most successful value investors, Greenblatt started and ran the Gotham Capital hedge fund from 1985 until 2006. Greenblatt's value focus was based on what he dubbed his "magic formula." The magic formula measures companies based on their earnings yield, which is the inverse of the price-to-earnings ratio, and return on invested capital, or the after-tax net operating profit a company generates from the capital it has invested.

What's interesting about Greenblatt's approach is how different it was from Graham's. While Graham looked to buy deeply discounted assets, Greenblatt focused on a company's returns and its earnings-based valuation. This strategy proved very profitable for Greenblatt, who delivered a 40% annualized average rate of returns for investors over the 21 years he operated Gotham Capital.

As these successful investors demonstrate, value investing has evolved over time, encompassing a spectrum of strategies that all share the same common concept: Find a company that is undervalued by the market based on the true value of its assets, earnings, and any durable advantages it may possess.

Important value investing terms

At their heart, value investing strategies rely on being able to quantify a company's value compared to what it sells for today, looking to buy with a reduced downside risk and better odds of generating a positive return. There are many ways to measure what a company is worth, including its cash flows, earnings, and the assets it owns. There are also things that are more difficult to quantify, such as a company's competitive advantages, intangible assets including brand names, copyrights, patents, and other intellectual properties.

Here are some of the key terms to know.

Book value

Book value is the value of a company's total assets minus total liabilities as listed on the company's balance sheet in its quarterly 10-Q and annual 10-K SEC earnings filings. As a valuation tool, book value is often expressed as the price-to-book value ratio, or book value per share.

Balance sheet

Found in a company's quarterly 10-Q and annual 10-K SEC filings, the balance sheet is where you'll find a closer look at a company's assets and liabilities. The balance sheet is a very important thing to understand, as it's a breakdown of what a company owns and what it owes.

Assets

Assets are the things a company owns, including tangible things like inventory, cash, property, equipment, accounts receivable (money it's owed by customers), and intangibles like goodwill and intellectual property such as patents and trademarks.

Liabilities

Liabilities are the things a company owes, including debt like loans or bonds, taxes, lease payments owed on property or real estate, and accounts payable (money it owes to suppliers and vendors) to name a few important examples.

Current liabilities

Current liabilities are obligations a company must pay within 12 months. For instance, if a company owes $1.5 billion in debt, and $500 million of that is due to be paid within the next four quarters, its balance sheet would show $500 million under the current portion of debt and $1 billion under the long-term portion of debt.

By breaking out liabilities that must be paid in the short term, investors can gain a better idea about a company's financial strength to meet its obligations.

Current assets

Current assets are highly liquid items including cash, inventory, receivables set to be paid within 12 months, prepaid expenses, or highly liquid investments such as bonds. The more of these types of assets a company holds, the greater its financial flexibility in general.

Working capital

Working capital is current assets minus current liabilities. Often expressed as the working capital ratio, which is current assets/current liabilities, this is one way to measure a company's liquidity to meet its short-term obligations, as well as whether it has excess liquidity to act quickly if an opportunity presents itself.

Net income

Also called earnings, net income is a measure of a company's profits after all expenses are subtracted, based on GAAP -- generally accepted accounting principles. This is one of the most important metrics to use when evaluating a company, because it takes into account all of a company's expenses, even those that are noncash during a particular period but related to prior cash expenditures.

For instance, if a company spent $1 million to buy a new piece of equipment this quarter, that purchase would likely have very little impact on net income. However, the company would be required to depreciate the expenditure going forward, generally over the expected life of the piece of equipment, so each quarter, its depreciation expense would reflect a portion of this expenditure.

As a valuation tool, earnings is normalized as a multiple to a company's share price, called price-to-earnings or P/E ratio. However, just because a company's P/E ratio is lower than that of the market or its peers doesn't make it a sure-fire value stock, and a high P/E ratio doesn't always mean a stock is "expensive." In short, don't use the P/E ratio as a stand-alone valuation tool that you base buy or sell decisions on.

Cash flows

A bit of a catch-all term, "cash flow" has multiple components, depending on where in the business it's being measured. A company's quarterly and annual earnings reports will include a statement of cash flows, which breaks out different measures of cash flows based on different activities, including operating, investing, and financing. In short, these activities describe cash flows as follows:

Operating cash flow measures the cash generated by a company's core business operations. For instance, Ford Motors' (NYSE: F) core business is making and selling cars and related parts and accessories, so its operating cash flow measures how much cash is left over from selling cars after all the operating expenses related to building and selling cars are accounted for. This is one of the most important cash flow metrics, as it measures what should be the biggest generator of cash flows for a company.

Cash from investing measures the inflow or outflow of cash from the purchase (capital expenditure) or sale of assets such as property or equipment, the acquisition of other companies or divestiture of parts of the business, or the purchase or sale of short-term investments such as bonds and stocks.

Cash from financing is related to a company's actions to raise capital and, to some extent, to return capital to shareholders. This includes issuing stock or repurchases and issuing or repaying debt, as well as dividends paid.

Free cash flow is operating cash flow minus capital expenditures. This is considered one of the most valuable cash flow metrics, using a company's core cash generation and subtracting the money it spends to buy new equipment, build a factory, or improve existing capital assets. In general, a company's free cash flow can be a better measure of its "true" profitability, since net income, as described above, can be heavily influenced by noncash items.

However, free cash flow can vary wildly from one period to the next for various reasons, such as a company making large capital expenditures to build a factory or make an acquisition that can have a significant impact on cash flows in a nonrecurring way.

For this reason, it's typically a good practice to analyze cash flow metrics such as operating cash flows, free cash flows, and net income together and to look at them over a period of multiple years, not just a single quarter or even year. And when you do see a significant variance, dig into a company's financial filings to learn why.

EBITDA

Shorthand for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization, EBITDA is a common proxy for cash flow. Much like cash from operations, this can be a handy metric to analyze a company's core business results. Obviously a company must still pay taxes and interest on debt, but these things can vary greatly depending on a company's balance sheet (for debt) and where it operates (for taxes), while depreciation and amortization are noncash expenses for prior capital expenditures, not operating costs.

By adjusting for these items, investors can get a better understanding of the profit potential of a company's core operations while still being cognizant of the real-world impact of the excluded items. It's worth noting that many companies also report "adjusted" EBITDA, which excludes items other than interest, tax, and depreciation and amortization expense. If you see this metric, take the time to learn what other items that company is excluding and why.

Discounted cash flow

Discounted cash flow is a calculation used to determine the future value of a company's projected cash flows. In general, this analysis is only useful for companies with established businesses and fairly predictable future cash flows, such as a large, well-established utility. The basic premise is since the value of money changes over time (inflation), investors should determine how much future cash flows are worth today.

While more complex and not viable for more speculative stocks or companies with highly cyclical and less-predictable earnings, the discounted cash flow analysis can help investors find value that's not as easily identified based on more mundane metrics. That makes it a popular part of many value investing strategies.

How to find value stocks

Value investing requires a lot of research plus facing the fact that you'll potentially look at dozens of companies before you find a single one that's a true value stock. For this reason, using tools to help identify potential candidates can save you a lot of time.

A stock screener is a valuable tool to search for stocks based on certain parameters. For instance, you can utilize a screener to find stocks that meet certain metrics, including cash flows, price-to-earnings -- or P/E -- ratios, or just about any other financial measure that can be derived from a company's financial reporting.

Moreover, there are a lot of high-quality screening tools available online, with many completely free of charge. Chances are, your current online discount broker's website has a stock screener built in, and it may have some preset screens for value investors already set up and ready to use with the click of a mouse or the tap of a finger.

However, even the best stock screener isn't the final step in finding value stocks; in general, it's just a way to get a list of potential candidates. The next step is to dig deeper than just what the screener found. For instance, if you run a screener based on book value, a stock that's trading below 1 times book value -- meaning its shares sell for less than the value of its assets -- isn't necessarily a value stock.

For instance, a business trading for less than book value that's not profitable could be a real value trap if it can't swing into the black. After all, it has to make ends meet somehow, and that could include selling off assets, issuing more shares, or taking on debt, all of which would consume book value per share.

The same can apply to earnings-based value hunting. A stock trading at a discounted P/E ratio to its typical valuation or that of the market average at the time is no promise of value.

So what do you do? Dedicated value investors will roll up their sleeves and start digging into a company's financial reports, its quarterly 10-Q and annual 10-K reports in particular. These reports are a treasure trove of data about recent results and operations, and they also provide some historical context around a business's operations and financial results.

Moreover, it's a good idea to not just look at the financial reports for a company on your list. A savvy value investor will take the extra time to research a company's biggest competitors as well. This will help you develop not only a better understanding of whether there's value in the company you're focusing on but also deeper knowledge about its industry.

Frankly, the key behind the value-seeking process isn't so much that you're trying to find value as trying to disprove a stock as being a value investment. It's not uncommon for a value investor to research dozens of companies before finding one worth buying. This is a strategy that's predicated first on finding a margin of safety, so be prepared to find lots of great companies that don't meet the standard.

Is value investing right for you?

If your primary investing goal is to keep your risk of permanent losses to an absolute minimum while increasing your odds to generate positive returns, you're probably a value investor at heart. In general, value investing means more time researching stocks and doing your homework to measure a company's intrinsic value to determine if there's a big enough margin of safety.

Furthermore, pure value investors tend to own more concentrated portfolios, since the value-finding process eliminates far more stocks than it uncovers. It can also be a frustrating way to invest during a bull market, particularly if many of the stocks you crossed off of your buy list for one reason or another only continue to gain in value from where you thought they were already too expensive.

But when the market falls or delivers below-average returns, the margin of safety in the price you pay for an investment can make it much easier to ride out a downturn, knowing that eventually you'll be able to attain a fair value for your investment at a profit versus what you paid.

The most important thing to understand is that like most stock market investing strategies that work, value investing requires a long-term mindset. As economist John Maynard Keynes said, "the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent." The lesson is that while occasionally one's timing is lucky and an investment pays off very quickly, even a value-focused strategy doesn't guarantee quick gains. Mr. Market doesn't always "realize" it was wrong about a stock or that it undervalued an asset very quickly.

Add it all up, and value investing may be ideal for you if you're willing and able to put in the time to research individual companies and accept that the vast majority of your research will generate a list of companies that don't meet value investors' standards.

But even if you decide you're not cut out to be a value investor, understanding basic value investing strategies will make you a better investor overall.

Three examples of value stocks

Company | What Makes It a Value Stock (as of This Writing) |

|---|---|

Hospitality Properties Trust (NASDAQ: HPT) | Big discount to its historical cash flow multiple; high yield with relatively low cash payout ratio |

Wells Fargo (NYSE: WFC) | Substantial discount to historical book value multiple; highest dividend yield in almost a decade |

Ford Motors (NYSE: F) | Lowest cash flow multiple in years and well below industry average; near-record dividend yield |

All three of these stocks were first identified with a stock screener; the author then spent substantial time reviewing the companies' earnings filings, comparing them to those of industry peers, and finally considering the near-term and long-term economic risks and opportunities.

All three meet the minimum expectation of well-run, high-quality businesses with durable advantages. At the time of this writing, they traded at substantial discounts to their historical valuations to create a wide margin of safety for investors while also offering substantial prospects for capital growth. Let's take a closer look at what makes each of these stocks appealing for value investors right now.

Hospitality Properties Trust

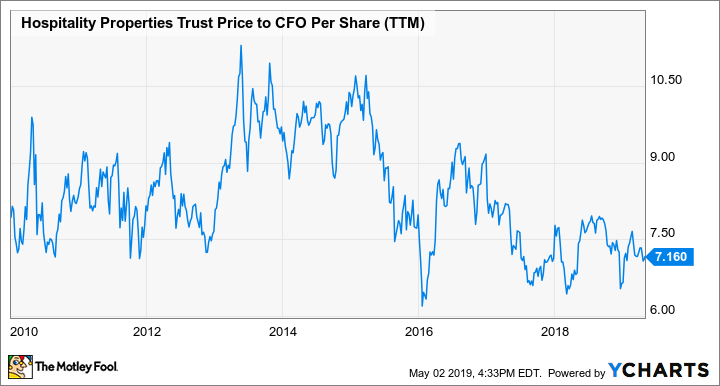

Hospitality Properties Trust is a real estate investment trust -- or REIT, a corporate structure that's advantageous for companies in the property business -- that makes about two-thirds of its money from hotels it owns and about one-third from roadside travel centers. In recent years, it has spent a significant amount of money to revitalize and renovate a large number of those properties.

Of course, renovating hotels means fewer rooms to rent at the same time you're spending more cash. The dual impact of these things has caused the company's cash flows to fall while its debt load has increased. Operating and free cash flow fell 13.4% in 2018, while total long-term debt increased 32% from 2017 to the end of 2018. At the same time, investors were more leery of a recession, which can be bad if you're a hotel operator.

So you have a hotel stock that added debt during a rising-rate environment and spent a lot of money on renovations, potentially right before a recession. What's not to love?

Here's where the value comes in: Hospitality Properties stock fell 20% from early 2017 to early May 2019, sending its valuation plummeting to 7.2 times both trailing cash from operations and funds from operations -- or FFO, an important proxy for earnings for REITs -- which was about as cheap as it had sold for since the Great Recession:

HPT Price to CFO Per Share (TTM) data by YCharts.

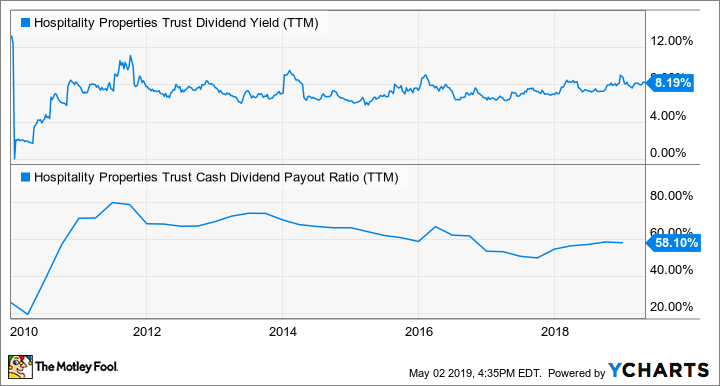

That's only part of what made it a potential deep value. The sell-off in Hospitality Properties' stock, along with two increases in the quarterly dividend, pushed the yield above 8%. Yet even with such a high yield, the company only paid out just under 60% of cash flows in dividends:

HPT Dividend Yield (TTM) data by YCharts.

Yes, the downside risk is that a recession could weaken its business even more just as it's taken on more debt and hasn't completed its renovation plans. But this was where its already-low cash flow multiple, as well as the wide margin of safety in the dividend payout, made it a solid value play.

Sure, there could be short-term pain if recession hits, sending even more shareholders selling in fear. But smart, value-minded investors should be happy to collect the generous dividend while they wait for the market to recover and while enjoying the long-term gains provided by the durable value of the company's valuable real estate assets.

Wells Fargo

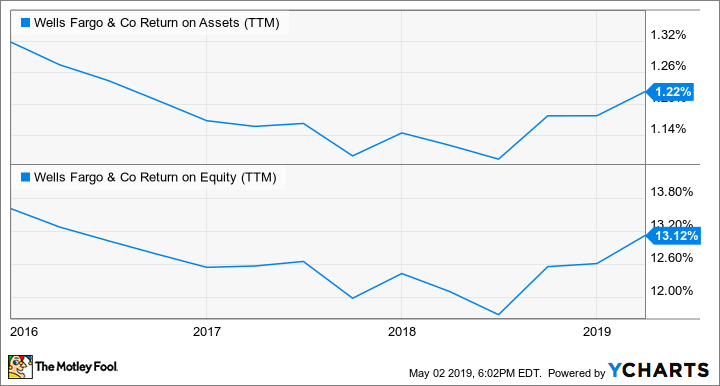

When it comes to its public image, Wells Fargo is a troubled bank, given the hangover of its "fake accounts" scandal, which led to millions in fines, caused regulators to restrict it from growing its assets, and cost it two CEOs following the abrupt and unexpected retirement of Tim Sloan. Add it all up, and Wells Fargo was easily the worst investment of America's four biggest banks from 2016 through early 2019:

While other banks were making investors money, Wells Fargo stock lost value. Even when adding in the benefit of its dividend -- one of the most generous in banking -- Wells Fargo investors lost money over this period.

This sell-off put Wells Fargo squarely in the sights of many value investors. That's because, despite its notable public relations challenges and the Federal Reserve's restriction on asset growth, Wells Fargo still retains one of the best loan portfolios in the banking industry and incredibly low-cost deposits, and it traded for a meaningful discount to the typical price you'd pay for the company during periods in its history without that overhang:

WFC PE Ratio (TTM) data by YCharts.

As you can see, Wells Fargo's valuation, based on both earnings and book value, has generally been substantially higher.

For value investors willing to ride out the company's restricted-growth environment, that creates some margin of safety. That's particularly true when you consider that the bank didn't see a major outflow of deposits following the "fake accounts" scandal, and Wells Fargo's returns on assets and equity have remained well above the industry targets of 1% and 10% respectively:

WFC Return on Assets (TTM) data by YCharts.

Furthermore, Wells Fargo's dividend is one of the higher yields in banking while consuming less than one-fourth of cash flows. That makes for a solid base of returns while investors wait out the Fed's restriction on growth. Furthermore, management has aggressively repurchased stock -- more than 7% of shares outstanding from the first quarter of 2018 through the first quarter of 2019 -- while its restriction on growth has been in place.

Add it all up, and it's a combination of high-quality assets trading for a meaningful discount to historical valuations, a very well-run business with durable competitive advantages, and a high-yield dividend to help generate returns while the value thesis plays out.

Ford Motors

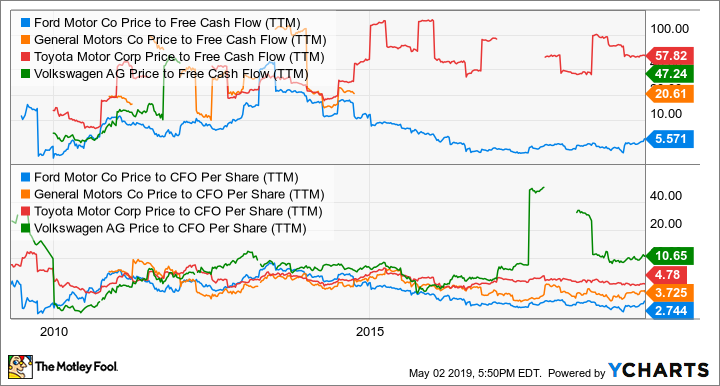

Alan Mulally, the CEO who led the company through a remarkable turnaround that began prior to the Great Recession, retired in 2014. In the five years following his retirement, Ford's stock price fell more than 60% as management struggled to hit on a winning strategy in a changing global auto market.

Furthermore, a cyclical drop in demand for auto sales in 2018 weighed on the company's cash flows, along with higher expenses it wasn't able to bring down as quickly as investors wanted to see.

Here's the thing: Ford isn't a troubled company, and it's certainly not in any financial straits. The market was just very underwhelmed with its results, and after multiple years of Ford struggling to deliver big improvements, investors want to see results.

As a result, Ford became deeply discounted to its cash flows, both on a historical basis and compared to other automakers:

F Price to Free Cash Flow (TTM) data by YCharts.

The prolonged decline in its share price also pushed Ford's dividend yield well above 5%, while its cash payout ratio, which has consistently been below 50%, gave it a wide measure of safety.

F Dividend Yield (TTM) data by YCharts.

The Ford balance sheet, which held almost $34 billion in cash and short-term investments as of mid-2019, was also a source of strength. That massive cash cushion served a critical purpose for Ford, positioning it to ride out a prolonged downturn in auto demand while maintaining its dividend. That's very important to the Ford family, which still has a controlling interest in the company.

So yes, Ford has things to work on, and the cyclical nature of the auto industry creates additional risk and uncertainty. But it remains one of the most iconic names in the auto business, and it continues to prove itself a cash-cow business even with its ongoing challenges. Add in its fortress of a balance sheet and cash flows that far exceed what it needs to maintain the dividend and still invest in the business, and Ford checks off many of the critical boxes that value investors need to see.

How value investing helps you invest better

Value investing certainly requires a commitment to put in the research finding stocks that offer both some margin of safety on the downside and enough upside -- whether in dividends earned or share price appreciation -- to make them worth owning. Furthermore, you may choose, like Buffett, to not be a pure value investor, instead using basic value investing strategies as part of a broader approach to finding high-quality companies at a fair price.

So whether your future path is one of looking for "cigar butts" or using value investing principles to find a fair price for the companies you want to buy, understanding and applying the concepts that Benjamin Graham wrote about almost 90 years ago and that others have added to and improved upon since will make you a better, more successful investor.

Jason Hall owns shares of American Express, Ford, and Hospitality Properties Trust. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Berkshire Hathaway (B shares). The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance