40 years later, reporter’s book revisits KC Hyatt disaster and its lessons for today

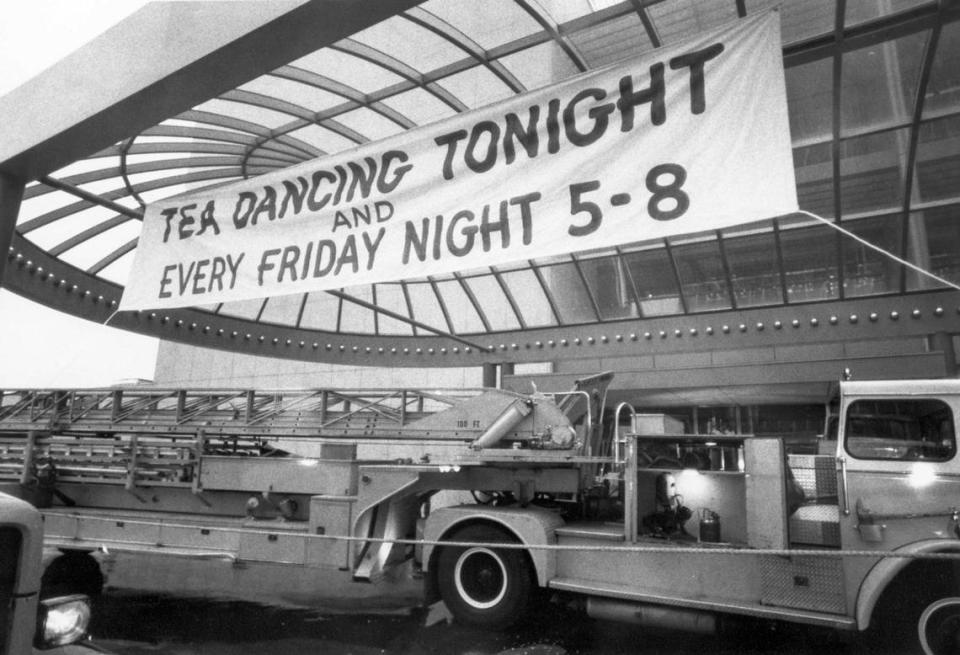

Two giant skywalks suddenly pull from their moorings above the lobby of the Hyatt Regency Hotel during a Friday night Tea Dance that summer of 1981. The casualties are high: 114 dead, 200 injured.

From out of the swirling concrete dust came anger and disbelief. Investigators determined the upper bridge broke first, then heaved both skywalks down. A state agency blamed the top structural engineers and revoked their licenses. Lawsuits piled up but all were settled; no trial ever gave voice to the victims. First-responders suffered for years too. Divorces mounted, alcohol and drugs took hold. Jobs were lost and in at least one case, a suicide.

The skywalk disaster did bring new safety standards into how our buildings are designed and built. It fostered fresh “green” environmental designs and led to long-needed counseling for rescuers.

And if one word best describes why the skywalks fell, it comes from James B. Deutsch. “Complacency,” declared the judge who presided over the licensing matter. Simple design and construction tasks were taken for granted. “Oh, I’ve done this a hundred times,” Deutsch said the engineers assured themselves. “Do I really need to check things?”

Forty years after the Hyatt disaster, former Kansas City Times reporter Richard A. Serrano delves into that awful night and its aftermath in his new book, “Buried Truths and the Hyatt Skywalks: The Legacy of America’s Epic Structural Failure” ( Purdue University Press). Here is an excerpt:

Waitresses served appetizers in the jam-packed hotel lobby. Bartenders staffed a half dozen portable bars. Forty or more Hyatt employees slid through the vast lobby crowd, evening out lines so no one waited too long for a glass of Oh Be Joyful. Security guards occasionally urged partyers to “calm down” but rarely was anyone asked to leave. No corner was barricaded, nothing off limits. The vast hotel atrium opened loud and jubilant, pleasant and welcoming to all. The summer sun slowly set, and the skywalks glistened.

James McMullin arrived early around 3 p.m. with family and friends and scooped up two tables near the bandstand. He was 54 years old, short and bearded. For years he toiled as a criminal defense attorney in the courtrooms downtown. He had served at the end of World War II and during Korea; the GI bill saw him through school. Outside his suburban home he flew the Marine Corps flag.

For tonight’s dance McMullin ditched his courtroom suit and tie for a red sports shirt, shorts and knee socks. “We went every time,” he long remembered. “We liked the World War II music. That was our generation, the tea dances. We loved it.” As the lobby filled up, McMullin purchased a handful of drink tickets and headed for one of the bars. “I got in line because it was hot,” he remembered. He returned carrying gin and tonics. “I was walking back and all of a sudden there was this woof! It threw a lot of dust everywhere. Then came a tremendous silence.”

Carmen and Virginia Vigliaturo arrived early too. They often did. They lived in the largely Italian-American community on the city’s old North End. For 25 years they had been married. He set type in the composing room at the local newspaper; Virginia worked in the advertising department at Sears. “We went every week. We enjoyed them,” she recalled. They adored dancing so much, they attended many weekend weddings too.

“I loved the music,” remembered Carmen. “The Big Band music. That’s why I married her. Because she was a dancer.”

He left work in his Buick, picked Virginia up at home and they drove to the new Hyatt Regency Hotel. They met his brother Sam and his wife Kaye. “We went casual,” recalled Virginia. “But people were coming in and they were all dressed up. Not us. I wore a red dress. He put on some casual slacks.”

The Vigliaturos registered for tonight’s dance contest. They found an open circular couch in one of the lobby alcoves, not far from underneath the two massive skywalks suspended from the ceiling rafters overhead, like floating bridges arching across the lobby floor. Below, flowers were arranged around the lobby furniture. Carmen and Sam headed for the bar; their wives asked for pina coladas. “Carmen,” Virginia remembered, “was walking back toward us when the skywalks fell.”

Keith Jansen and wife Shirley, a Nebraska couple in their 30s in town for a weekend floral show at the hotel, sipped champagne and snacked on popcorn below the twin walkways. But she was tired, her feet sore. So Shirley returned to their guest room and Keith decided on an evening swim. To reach the pool he crossed over one of the skywalks, stopping to admire the lobby festivities below. “Oh it was beautiful,” he gushed many years later. “Oh my goodness. Almost like a palace. Such elegance. And the staff was so pleasant to us, so accommodating and our room was extremely beautiful.”

And the skywalk? “It didn’t sway so much, just more of a thump, thump sound from the kicks. But I did feel secure. After all you have architects and designers who know how to build these things. Why should you be afraid?”

Jansen watched a while. “All those people were having such a wonderful time down there. The women in pretty dresses. And the fellas had loosened their ties. Everyone was laughing and joking.” Guests near him on the skywalk “were stomping their feet and having a great time with the music,” he remembered. “The drummer in the band, I’d never seen a drummer use sheet music before. I was just in awe of a drummer playing and turning the sheet music.”

Mark McGonigle and friends ambled in under the two skywalks, grinning at the older couples. He was home that summer from a Catholic seminary in Texas. They were in their early 20s, out for a Friday night lark. They wanted to drink and dance and laugh. “We had no idea there was a dance contest,” McGonigle remembered. “My dad had taught all of us boys how to swing dance to the old-school music. So we entered the dance contest. They put numbers on our backs.”

McGonigle spotted an older man and could not stop staring at him. Even while dancing, his eyes followed the stranger. “He was a middle-aged guy in a plaid leisure suit, a gold nugget ring on his finger and this gold horn necklace thing on his chest. A gaudy ring that was just a big blob of stone, flashy, the size of a rabbit’s foot. And I’m thinking, what a cheeseball.” In a few minutes the young McGonigle and this older gentleman would be holding hands, praying.

Laquita Allen marveled at the couples spinning across the lobby floor. She was here for a Fuller Brush dinner at the hotel. A regional vice president, she flew in from Texas. She took a room in the hotel guest tower. Now during the evening cocktail hour before the company banquet, Allen and other sales reps sneaked away, lured by the music and laughter below.

“I was just crossing over the second-floor skywalk,” Allen recalled. “People were standing two- and sometimes three-deep trying to see over the side. I wanted to stop and look but not a chance. You couldn’t see over the railing.” Just as she stepped off the skywalk, “I heard this horrible popping sound.”

“I was standing under the skywalks,” remembered Julie Turner-Ruskin. She was 31 with auburn hair, in five-inch heels and an evening dress. The band was featuring her as tonight’s vocalist. “I couldn’t see over the crowds to watch. Because I’m not real tall I couldn’t see. So I decided to move up and I just set foot on the stage and suddenly the whole thing, it looked like it was in slow motion.”

For Tim Lindgren, the hotel’s general manager, tonight’s receipts were turning out fantastic. He could see that, standing at the top of the escalator on the second floor, overlooking the noisy lobby. Some were overnight guests, especially the flower and Fuller Brush people. Most though were local area couples. Tonight promised the hotel’s best sales yet. From 1,500 to 2,000 people were packed in and around the Hyatt atrium.

“You reach a point, you know, where you can’t handle it or service it,” Lindgren later explained. But he stressed, “we never got in that situation. We never got complaints or problems with people getting drinks.” The lobby was filled, but not too worrisome. “Did we encourage people to use the skywalks?” he asked himself. “Not that I remember. But people did. They stood on the skywalks and had their pictures taken.”

No one discouraged them from collecting up there. Some revelers heard the master-of-ceremonies urging the overflow onto the hanging bridges. But Lindgren was not sure. “I don’t remember the emcee saying that. He generally encouraged people to dance everywhere through the building and enjoy the facilities.” Including the skywalks? “Anywhere they could hear the music.”

At the top of the escalator the first lilts of “Satin Doll” wafted up. “There was a speaker right near where I was standing that was projecting the music from the band and I don’t have the greatest hearing in the world,” Lindgren recalled. “And so there was the combined noise that I heard. It was not a singular noise that I heard. It wasn’t just the skywalks.”

Three young friends gathered at the middle of the lower bridge. Above they could see the bottom of the connected upper skywalk, below them the twirling dance couples. Mona Danner had just been accepted into graduate school; she tipped her head and raised a glass of red wine. “Thank you, God,” she rejoiced. “It’s good to be alive!”

Sally Firestone, in pink blouse and spectator pumps, a career woman fairly new to Kansas City, leaned slightly over the skywalk railing. She wished she could dance like that. “We were mostly there to watch and learn,” she recalled. “I remember hearing a noise and that’s all I know.”

Cathleen Burnett, fiercely afraid of heights, felt it. “The skywalk was full of people and we were in the middle,” she recalled. Burnett had been Danner’s undergraduate professor. “At some point I heard a crack. I said to everybody, ‘I’m getting off of here,’ and I started walking to the right side and they didn’t come with me. Maybe the music was too loud and they didn’t hear me. I got all the way to the end but I didn’t get off. I was walking; I wasn’t running. I was almost off and the skywalk started to fall. I was one or two steps away and I started to go down. My hands tried to hold on.”

Directly below, the Hanson sisters from a Kansas farm family had squeezed inside the lobby doors. They pushed ahead for drinks, then shouldered back toward the front entrance. They stretched on their toes, straining to glimpse the band, never aware of the skywalks above them. Both in their 20s, they had never even heard of skywalks.

“My sister and I were standing together,” remembered Rachael Hanson. “I heard a loud noise. And then it was like being in a building that had been bombed. Just the roar of the skywalks coming down.” Her sister Melanie realized “Rachael was hit and we never even ducked. Oh my God I’ll never forget it, it happened so fast. I was bent double, my face between my knees on the floor.”

Ronald Trefts from St. Louis lit his pipe outside the men’s room. “I turned my shoulder and I heard a woman scream. I mean that woman screamed really loud.” Cameraman David Forstate was preparing to film a TV interview with the band leader. “We heard a rumble,” Forstate recalled. “The whole building shook.” John and Marie Driscoll stood in line for a table at the lobby’s second-tier Terrace Restaurant. “I saw this skywalk sliding down the walls,” she remembered. Neal and Sally McCaffrey had just sat down to eat. They ordered iced tea. The two skywalks fell and a water pipe burst. Sally gasped, “If those people didn’t die, they are all going to drown.”

Evelyn Gubar and husband Joe had come to celebrate her birthday. He dressed well as always, tonight in a full suit. “He was the dancer,” she beamed. “I wasn’t very good. But he was a wonderful dancer and a wonderful golfer. And I called him Java Joe because he liked coffee.”

They had been married 30 years, with a son and daughter. He sold commercial building supplies on State Line Road. She had feathery-light hair and together they shared breakfast out every morning. He was the love of her life, her anchor. “He got in the line for the bar,” Evelyn remembered. He was ordering her a martini, a Scotch on the rocks for himself. “I was looking right at him and he was looking and smiling at me. That’s when they came down and fell right between us. It killed him. It knocked me over to my left. But he was looking back at me with his smile, and that’s how he died.”

Richard A. Serrano shared a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Hyatt disaster while he was a reporter at the Kansas City Times, then The Star’s sister paper. “Buried Truths and the Hyatt Skywalks” is his sixth book.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance